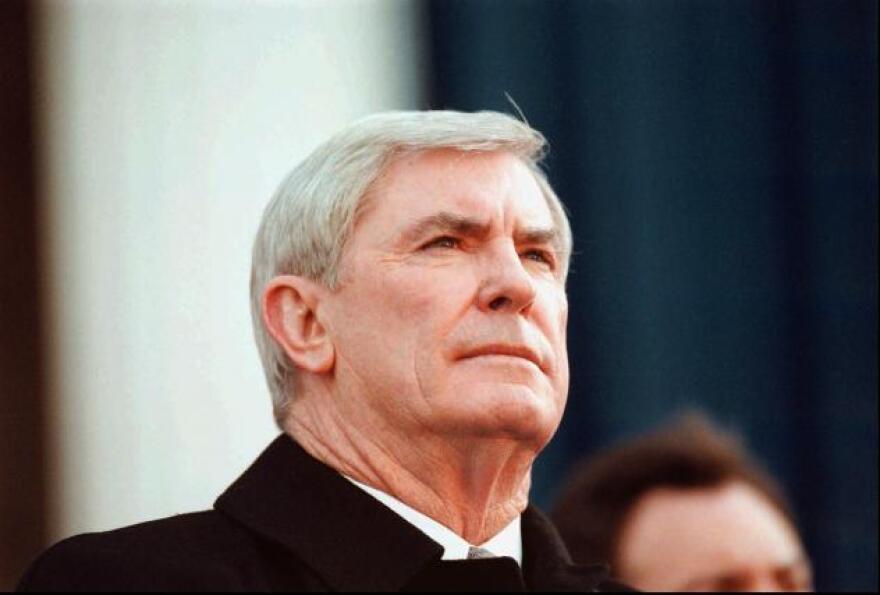

The late-Governor Kenny Guinn had a sterling reputation in Nevada. But a Las Vegas journalist and author casts some doubt on that legacy.

"The Anointed Son: A True Story of Greed, Power and Blind Trust" was written by Dana Gentry, a journalist at the Nevada Current online news site.

The book is predominantly taken from legal transcripts related to lawsuits against Kenny Guinn's son Jeff Guinn and his hard-money lending company, Aspen Financial.

Aspen Financial acted as a broker between cash lenders and, in many instances, developers. Sometimes borrowers couldn't, or didn't want to borrow from traditional banks. Borrowing from hard-money lenders carries a higher interest rate. Lenders, on the other hand, go into it knowing that it can bring a higher return but at a greater risk.

Aspen Financial was brokering deals between lenders and developers during Nevada's boom years. Investors, including those who ended up suing Jeff Guinn, made a lot of money.

However, when the recession hit, those profits disappeared.

One of the main people to sue Jeff Guinn was Donna Ruthe, the widow of a well-known Las Vegan Chuck Ruthe. Chuck Ruthe and Kenny Guinn were friends of many years, according to Gentry.

Ruthe's attorney argued that disclosure forms outlining the riskiness of the laws, which are required by law, were not signed.

Gentry explained the forms were created by a legislative committee that included Jeff Guinn as a way to better regulate the hard money loan business.

“One of the things that came out of this committee was a disclosure form that each investor-lender is required to sign before the hard money broker accepts their money,” she said.

However, in her research, Gentry found that wasn't happening.

“Records that I have looked at clearly show that these investor-lenders were not signing these disclosure forms before giving Jeff Guinn their money,” she said, “The Ruthes may have been so comfortable with their relationship with the Guinns that they may not have ever looked at them.”

In his own testimony, Jeff Guinn said he had a special dispensation from the state to bypass that regulation; however, Gentry talked to regulators and found "they gave Jeff Guinn no such pass."

A judge recently awarded some plaintiffs in a lawsuit against Aspen Financial $800,000 but did not find an overarching pattern of fraud.

“I don’t think Donna Ruthe considers this a complete victory because she had $7 million at stake and she’s not getting back anywhere near that amount," Gentry said, "However, I don’t think Jeff Guinn, who is back in business as a hard money lender now, can consider it a victory when the judge said he engaged in fraudulent behavior.”

The judge found that in four of the 26 loans in question Guinn concealed information. Those four loans were out of around 100 loans Guinn was handling at the time.

Gentry says the more she looked into the son's issues, her respect for Kenny Guinn changed.

She said Gov. Guinn had a chance to sign a law tightening regulation of the loan industry but didn't.

“I think there were a couple of instances in which Jeff Guinn opposed certain regulations and Kenny Guinn went along with his son’s position. Now, what was in Kenny Guinn’s mind at the time was he was deferring to his son’s judgment I have no idea," she said.

Of particular concern to Gentry is the blind trust that Gov. Kenny Guinn created when he became governor. The blind trust held Gov. Guinn's financial interests and it was controlled by his sons.

Gentry said in other states a blind trust is usually controlled by someone that can't benefit from the trust but Nevada doesn't have that type of regulation.

“That allowed his son, Jeff, to use his father’s blind trust basically as a piggy bank to fund his mortgage company. And the governor, without disclosure, invested in over 300 loans totally a face value of more than $36 million, during his eight years in office,” she said.

She pointed out that some of the money that was invested from the blind trust went to people who had made campaign contributions.

“Was there anything nefarious? I have no idea because I didn’t go and look and see if these people somehow got loans to buy tracts of land near highway exits or anything like that but that’s the kind of thing that is possible when these things are not disclosed,” she said.

Gentry said she had respect for Kenny Guinn before she started her investigation. He had been the school superintendent when she was in school and he had been willing to be part of political TV shows she had produced while he was governor.

“I don’t want to attack Kenny in any way," she said, "I just think that it’s the fault of regulators who basically were captured by the governor, the governor’s son and were afraid to speak up or maybe they weren’t looking, - I don’t know.”

Kenny Guinn unexpectedly died at his home in 2010. He was 73. He served as governor from 1999 to 2007.

Dana Gentry, journalist