A hundred years ago, America came up with what has been called its best idea—creating a national park service. When it comes to America’s national parks, Nevada has managed to be in the lead and at the rear—the first to have a national recreation area and one of the last states with a national park.

The legislation creating the National Park Service became law on August 25, 1916. But you can trace its beginnings to 1864, when Abraham Lincoln signed legislation protecting land in Yosemite Valley, California. A few weeks after that, he signed off on statehood for Nevada. Ulysses Grant was the general who helped make possible Lincoln’s reelection and the North’s victory in the Civil War. In 1872, as president, Grant signed legislation creating our first national park, Yellowstone.

But there wasn’t a federal agency managing these jewels until the National Park Service was born in 1916. It’s responsible for our national parks, recreation areas, and national monuments. And Nevada has a story to tell—and is part of the story.

The National Park Service reflects the thinking of the Progressive era. Early in the twentieth century, reforms included the idea of using some of the land for our needs—for example, water. That’s why the federal government planned a dam in the beautiful Hetch-Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park, for San Francisco to use. That’s also why the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902 was designed to build dams and reservoirs to help farmers irrigate their lands.

But another of our needs is recreation, or just to look at beautiful places and things. While the National Park Service helped meet that need, the Bureau of Reclamation wound up contributing, too. The construction of Hoover Dam created a reservoir to provide water to surrounding areas. It was originally called Boulder Lake, since it was behind what was then called Boulder Dam. With the dam completed in 1936, the area around it was named the Boulder Dam Recreation Area. You can read more about the lesser-known people who helped build the dam in this episode of State of Nevada.

In 1947, the Republican Congress made a change. It restored the dam’s original name. Now it would be Hoover Dam. That year, the lake it created was renamed, too. Its new name honored Elwood Mead, the commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation from 1924 until his death in 1936. The area around it became the Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

The dam and its surroundings weren’t designed to be a tourist attraction. The dam was built to harness the Colorado and provide cheaper water and electricity to surrounding areas. Lake Mead was to be the reservoir for those purposes. But while it was under construction, the dam began attracting tourists. And the lake became a popular stop for boating, swimming, fishing, and general rest and relaxation. As the Las Vegas Strip developed, several hotels had boats on the lake available for customers and for the entertainers who performed there. The Las Vegas News Bureau took numerous photos of stars enjoying themselves on its waters.

In 1964, Congress made it official, with Lake Mead becoming the first national recreation area under the control of the National Park Service. It includes Lake Mohave and the areas surrounding the Colorado River. It’s one of the most visited sites in the National Park System, with more than ten million visiting in its peak year. Nevada also boasts one of the least visited and most beautiful national parks, Great Basin National Park.

Around 1885, Absalom Lehman discovered some caves near his ranch in the Snake Valley, Nevada. A White Pine County newspaper reported, “Stalactites of extraordinary size hang from its roof and stalagmites equally large rear their heads from the floor.”

A Tonopah resident, Cada Boak, was active in the movement to build good highways. He publicized the existence of Lehman Caves. In response, in 1922, President Warren Harding designated Lehman Caves a national monument. The Forest Service ran it until Franklin Roosevelt gave control of all national monuments to the National Park Service. Meanwhile, Boak pushed to turn the area into a national park. Governor James Scrugham, a big advocate of parks, was all for it. Senator Key Pittman backed it. But stockmen opposed it. Grazing wasn’t allowed in national parks, and ranchers wanted to use the area for their purposes.

By the late 1950s, White Pine County’s economy was hurting. Senator Alan Bible thought a national park might help. He introduced a bill, supported by his Nevada colleague, Senator Howard Cannon. Democratic Representative Walter Baring introduced the same bill in the House. The measure would create a 147,000-acre national park on the Snake Range.

But ranchers objected because they said they needed the land to graze their livestock. Mining industry representatives fought it, too. They said the Snake Range could be valuable. Bible revised the bill to permit grazing and changed the boundaries to open the areas with the most potential for mining. But the forest service then said it had to cut back grazing there because the area had been overused, and the Interior Department recommended an increase in grazing fees. That increased the opposition. In turn, Baring introduced a different bill that would have reduced the park’s size and allowed mining and grazing. The battle of competing bills went on for several years. The Interior Department wouldn’t support Baring’s bill. With two different pieces of legislation from the same state, Congress was stuck and that was that.

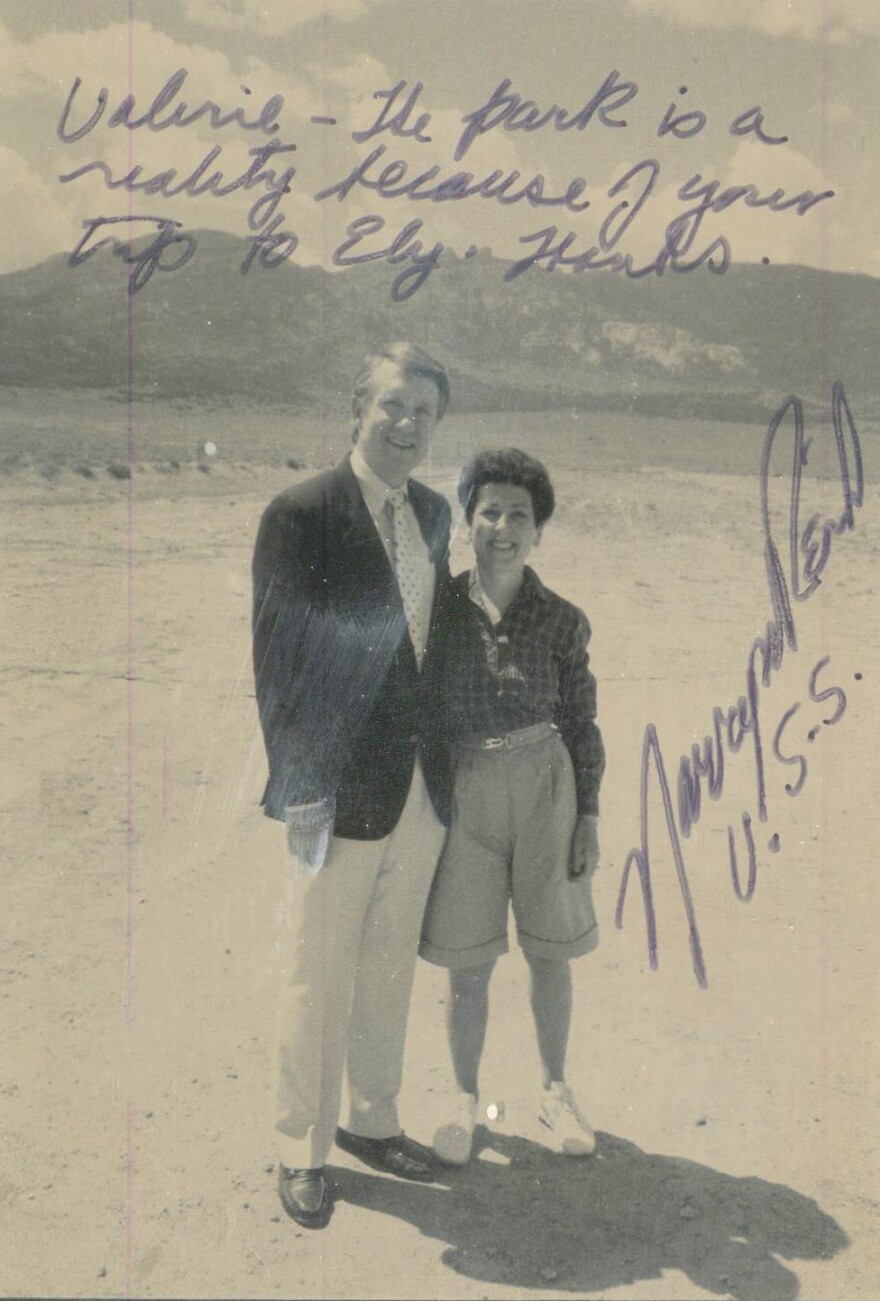

Until the 1980s, when mining and ranching had a little less power. Then-Representative Harry Reid introduced a bill to create the Great Basin National Park of nearly 130,000 acres. Nevada’s two U.S. senators, Paul Laxalt and Chic Hecht, proposed a smaller park—less than 50,000 acres. Each house passed its own bill, and a committee worked out compromise legislation: about 76,000 acres. It was signed in 1986. Thirty years later, it’s one of America’s least visited national parks. It’s off the beaten path—about 300 miles north and east of Las Vegas, an hour south and east of Ely, near Baker, Nevada. But when you see Wheeler Peak, and the bristlecone pines, and Lehman Caves … you may not think national parks, or this national park, was America’s best idea, as some say. But they’ll certainly take your breath away.