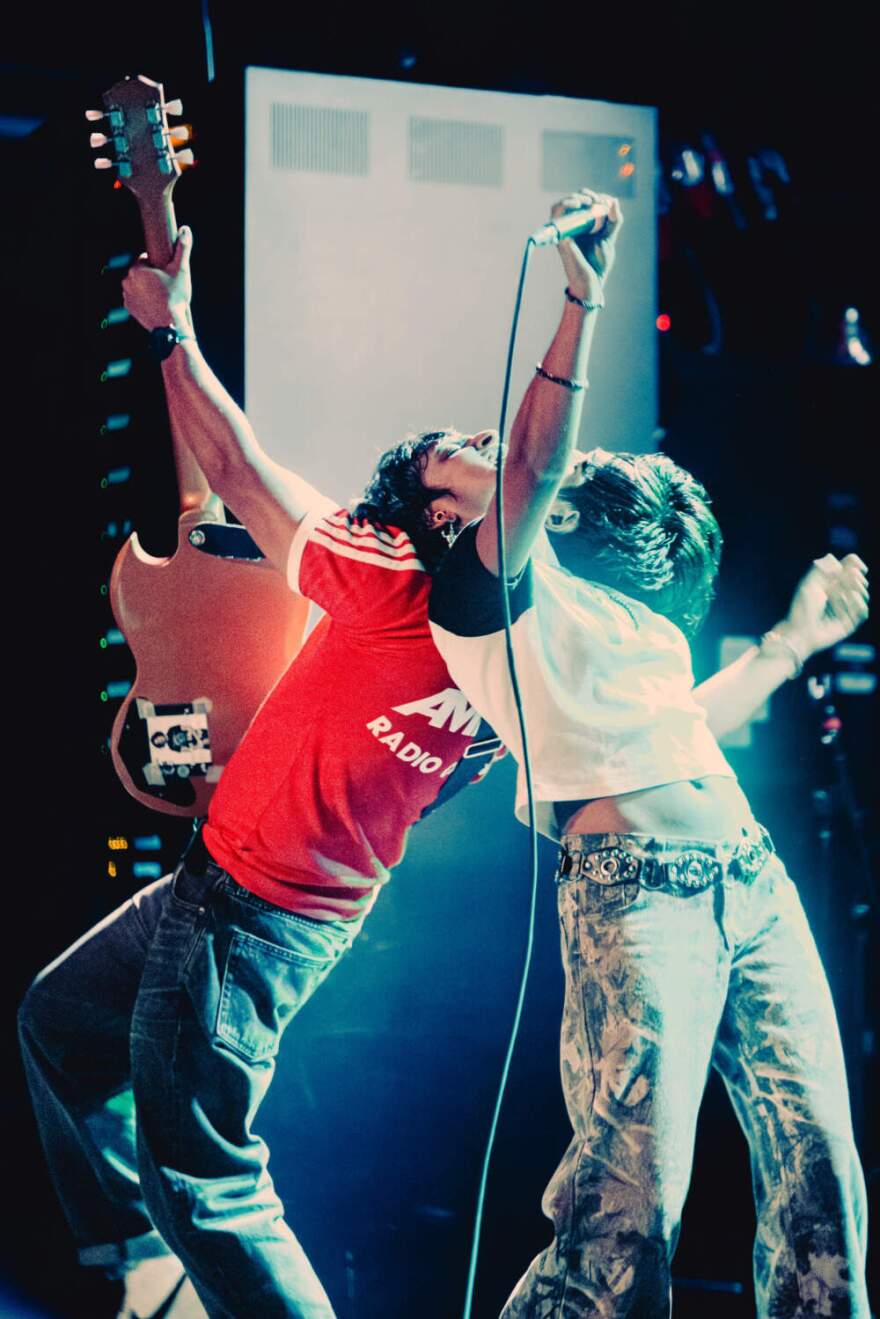

Ashrita Kumar captivates their audience, oscillating between screaming into the microphone and addressing the crowd tenderly at a recent concert in Boston.

Kumar is the lead singer of Pinkshift, a punk band from Baltimore. They just finished touring with their most recent album, “Earthkeeper,” which came out in August. The record is both provocative and introspective, calling out societal injustice and encouraging listeners to hold themselves gently in times of turmoil.

The word “Earthkeeper” originated in a journal entry Kumar wrote in 2023. The band was on tour at the time, and Kumar was reflecting on their place in the world and the nomadic nature of being a touring musician.

“‘Earthkeeper’ does speak to this idea of an intrinsic relationship with the Earth,” Kumar said in an interview. “Becoming the ‘Earthkeeper’ is this journey, I think that the record really goes through, both for a personal sense of empowerment and also for a collective sense of empowerment.”

Pinkshift formed in 2018 when Kumar met guitarist Paul Vallejo at Johns Hopkins University, where they both studied. They started playing music together but were missing a drummer.

So, they waited outside an on-campus practice room, hoping to recruit a third band member. That’s when they heard someone playing “Helena” by My Chemical Romance.

“We ended up just cold-knocking on the door,” Vallejo said, “being like, ‘Hey, you want to join our band?”

And drummer Myron Houngbedji wanted to join, rounding out the three-piece group. While in school, they started making demos and working them out at live shows. Once Kumar, Vallejo and Houngbedji graduated, with a number of science degrees between them, they turned their focus entirely to music.

Their proximity to the nation’s capital informed their work from the start. Houngbedji said he was working about 15 minutes away from the Capitol when the Jan. 6, 2021, riot unfolded. And, Kumar said, many people in their community are federal workers, impacted by the Trump administration’s mass layoffs.

“It’s all the more reason, at least for me, to actually address and talk about these kinds of things,” Houngbedji said, “because, you know, that’s where we grew up.”

The band uses its music and online platforms to criticize President Trump’s deployment of National Guard troops in cities across the U.S. and the flood of detainments made by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials.

On the last verse of “Love It Here,” the first song off “Earthkeeper,” Kumar shouts, “There’s no peace until there’s justice / They feed us lies, I won’t be silenced.” Kumar calls the song an “intention-setting” track that defines the rest of the album.

“‘Love It Here’ is a song that was very important to set right at the beginning, saying that this is where we’re coming from,” Kumar said. “This is the society that we’re living in, trying to figure out our own relationship to humanity. We’re living in a society that denies humanity to many, to most.”

At their Boston show, Kumar denounced ICE and the Israeli Defense Forces. The crowd erupted in cheers when the singer yelled out, “Free Palestine” and “trans lives are human lives.”

The band has taken action too, playing some shows to raise money for the Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund and amplifying mutual aid funds for immigrants in Washington, D.C.

Pinkshift follows a long lineage of punk artists who were loud about what mattered to them and unafraid to question authority.

“The culture of punk is so anti-establishment,” said Tavia Nyong’o, professor of American studies at Yale University. “It’s both about protest politics, but also about mutual aid.”

Protest anthems have been a staple in the genre since the U.S. subculture took shape in the 1970s. From Dead Kennedys’ “Holiday in Cambodia” in 1980, to Anti-Flag’s “Die for Your Government” in 1996, to Sleater-Kinney’s “Combat Rock” in 2002, punk bands have called out what they see as injustice perpetuated by the U.S. government.

Pinkshift is no exception. In 2024, the band put out their song “One Nation,” an unflinching condemnation of the ongoing violence in Gaza perpetuated by the Israeli government in response to the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas. On the song’s bridge, Kumar shouts “Kill a colonizer / Yeah, I’ll call you what you are / Stolen homes and screaming children / Liberty is not for all, huh?”

While protest defined punk’s roots, so did white men who largely dominated the scene at its inception. And as white supremacy crept into the scene through extremists who co-opted punk fashion and music, underrepresented communities broke off from the genre.

In the 1990s, women-fronted bands like Bikini Kill and Bratmobile spearheaded the Riot Grrrl movement. Black women in punk organized concerts under the name Sista Grrrl Riot, carving out space for Black queer punks. Afropunk formed to highlight the culture Black punks faced in the scene, and queercore — also known as homocore — put gay and trans punk voices in the spotlight.

“More and more people realized that there could be space for themselves as Black and Brown people in a genre that they would have felt unsafe or unrepresented in,” Nyong’o said.

Pocholo Itona, a bassist touring with Pinkshift, said punk is still largely white-dominated on the industry side, but not in smaller, local scenes. Black, Brown and queer people are still organizing to make the genre more inclusive.

“If you’re going to a show in D.C., Baltimore, Philly, and you’re paying less than $15,” Itona said, “it’s weird if there’s a majority of white kids in the room.”

Kumar said the only place they still feel like an outsider as a band comprising Black, Brown and queer people is at big music festivals where the majority of the acts are white.

And in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder in 2020, Houngbedji said music publications started releasing lists of Black and Brown bands to support, which felt tokenizing.

“We want the music to speak for itself and for people to include us in conversations about music because of the music, regardless of where we come from,” Houngbedji said. “It’s very easy, actually, for us to get pigeonholed into certain spots because of the way we present ourselves. But in reality, it’s just who we are.”

To Pinkshift fans, the music does speak for itself. Mia Panin attended the Boston concert with a friend. They said “Earthkeeper” felt like a personal invitation to foster community around them.

“I felt a lot of it was about keeping relationships that are important to you in times of political turmoil,” Panin said. “A lot of the songs, I think, felt very caring for each other in the community in a time like this.”

The members of Pinkshift said they work to cultivate that feeling of community at all the shows they play. Vallejo even said Kumar “gives out free therapy on stage.”

Over a musical interlude at the Boston concert, Kumar offered a timely call for unity in an increasingly fragmented cultural landscape.

“Tonight in this room, we are not divided units,” they said from the stage. “We are one. We all share the same wavelength.”

To make tangible, positive change in the world, Kumar said rage must be sourced from love for each other and the sense of collectivism that spurs from that love.

“When injustice is done to you, no matter who you are, I feel that within my soul, and I will fight for you,” Kumar said in an interview. “That is where my rage comes from because I love you as a person, and I love you and your humanity.”

That’s the theme of the last song on “Earthkeeper,” called “Something More.” Vocalizing softly on the verses, Kumar dares listeners to dream of a better world and trust themselves to create it.

“No law or bill or words that they say could ever match the power of your humanity,” Kumar said on stage. “Dream of something more. The future is full of optimism, innovation and hope.”

This article was originally published on WBUR.org.

Copyright 2026 WBUR