The Rat Pack — Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Joey Bishop and Peter Lawford — became synonymous with Las Vegas in the early 1960s, when their residency at the Sands Hotel turned the Strip into the entertainment capital of the world. They drank, performed, filmed Ocean’s 11, and built a mythology that still defines how people imagine old Las Vegas more than six decades later.

But the group most people picture when they hear “Rat Pack” wasn’t the original one. The name didn’t start with Sinatra. It started in the living room of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in Holmby Hills, California, years before anyone set foot on the Sands stage — and the story of how it migrated from a Hollywood drinking circle to a Las Vegas institution says as much about the city as it does about the men whose names are on the marquee.

Why were they called the Rat Pack?

The original Rat Pack belonged to the Hollywood power couple of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, who lived in Holmby Hills in western Los Angeles, near Beverly Hills. They liked to drink and entertain, especially with neighbors like David Niven and his wife, agent Swifty Lazar, restaurateur Mike Romanoff and his wife, and Sid Luft and his wife Judy Garland — herself a Las Vegas connection, since she headlined here and performed at The Meadows, the earliest local posh casino. Sinatra joined them once he moved to Hollywood, though he wasn’t exactly a key member at the outset.

Bacall gave the group its name, although exactly how it came about is less clear. This much is known: a night of carousing ended back at the home she shared with Bogart. She looked at her friends in various stages of inebriation and mood alteration and said, “You look like a pack of rats.”

The name stuck, although Sinatra reportedly didn’t much like it — but he didn’t complain because he liked Bacall, whom he briefly dated after Bogart’s death.

From Hollywood to the Strip

Martin and Davis had joined the fun with Bogart, Bacall and company, but they weren’t full-fledged members until after Bogart died in 1957, when Sinatra became the head of the pack. The center of gravity shifted. What had been a loose Hollywood social circle became something else entirely — a performing act, a brand, a Las Vegas phenomenon.

By 1960, the reconstituted Rat Pack came to Las Vegas to film Ocean’s 11 and headlined at the Sands in what became known as “The Summit” — a run of shows so electric that they essentially invented the modern Las Vegas residency. The members had occasionally filmed movies together before, fought with one another, and made headlines for their escapades (mostly Sinatra’s love life). But the Summit was different. It was the moment the Rat Pack became the Rat Pack as we know them.

Some began calling the group the “Clan,” which Sinatra preferred. But Davis was understandably sensitive about that word, so they remained the Rat Pack to their fans — and to us today.

Who were the Rat Pack members?

Frank Sinatra

Sinatra was the undisputed leader — the Chairman of the Board. But his Las Vegas story started at the bottom, not the top. He arrived at the Desert Inn in September 1951 during the lowest point of his career: his voice was failing, his records had stopped selling, and his marriage had collapsed publicly when he left his wife for Ava Gardner. He later joked about that first Vegas engagement, saying the audience got a filet mignon dinner and him for six dollars. It wasn’t until he reinvented himself — winning an Oscar for From Here to Eternity in 1953, then signing with Capitol Records — that he became the Sinatra who would own the Strip. He debuted at the Sands in October 1953 and it became his personal playground — a relationship with the hotel, and the city, that would span decades and survive career highs, mob investigations, and a punch from a casino executive.

Dean Martin

Martin was the group's indispensable counterweight to Sinatra — relaxed where Frank was intense, seemingly indifferent where Frank was controlling. His onstage persona as the perpetual drunk (the glass was often apple juice) made him the easiest member to underestimate and the hardest to dislike. He and Lewis had first played Las Vegas at the Flamingo in 1948, earning $15,000 a week — enormous money at the time — and after their split in 1956, Martin landed at the Sands under entertainment boss Jack Entratter. When Sinatra's blowup with Carl Cohen ended the Rat Pack's relationship with the Sands, Martin handled it characteristically: he quietly moved to the Riviera and became a part-owner. In 1973, he was the opening night headliner at the new MGM Grand, which became his home venue for the next decade and a half — a Las Vegas career that outlasted the Rat Pack itself by decades.

Sammy Davis Jr.

Davis was widely considered the most talented of the five — a singer, dancer, actor, and comedian who had been performing since childhood, touring with his father and godfather Will Mastin as the Will Mastin Trio. He first appeared in Las Vegas in 1946 at the El Rancho Vegas. But Davis’s Las Vegas story is inseparable from the city’s history of racial segregation. Las Vegas in the 1950s was known as the Mississippi of the West. Davis could headline the showroom but couldn’t stay in the hotel, couldn’t swim in the pool, couldn’t eat in the restaurant. He recounted being punched by a security guard at a movie theater for refusing to sit in the segregated section. When he began dating white actress Kim Novak, the threats came not from the public but from the mob — reportedly including a kidnapping by gangster Johnny Rosselli. Sinatra demanded the Sands give Davis accommodations befitting his stature, and when Davis was nearly killed in a car accident in 1954, he recuperated at Sinatra's home — the beginning of a bond that would shape both men's Las Vegas legacies.

Peter Lawford

Lawford was the group’s connection to political power. Married to Patricia Kennedy, he was John F. Kennedy’s brother-in-law — Sinatra called him “the brother-in-lawford.” It was through Lawford that JFK came to the Sands during the Summit in 1960, a visit with consequences that would ripple through both Washington and Las Vegas for years. When Kennedy later snubbed Sinatra by canceling a planned stay at his Palm Springs home, Sinatra blamed Lawford for not smoothing things over. Their friendship ended, and the Rat Pack was never quite the same.

Joey Bishop

Bishop was the least famous member but arguably the one who made the shows work. He was the comic architect — the writer and straight man who set up the spontaneous-seeming banter that audiences loved. While the other four had larger solo careers, Bishop’s role in the group was structural. Without him, the Summit shows would have been four famous men standing around with drinks.

The Summit at the Sands

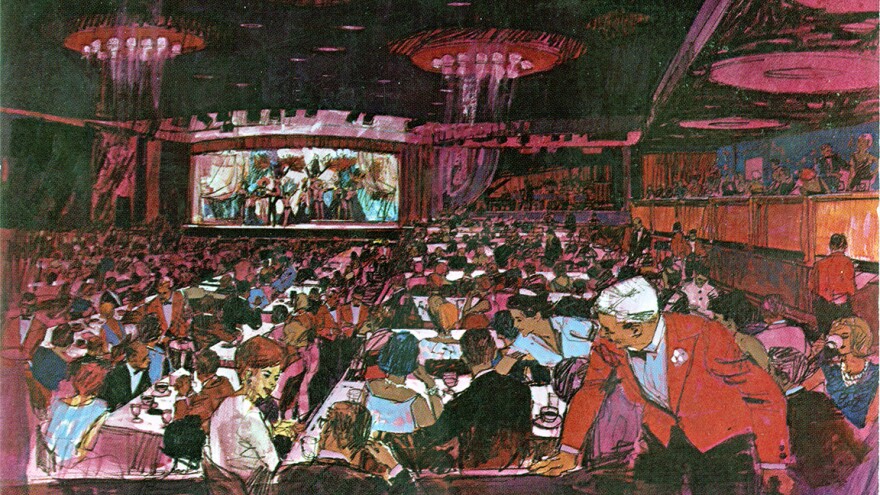

In January 1960, the five members were in Las Vegas to film Ocean's 11 — a heist picture that doubled as a love letter to the Strip, shot on location at the Sands, the Sahara, the Riviera, and the Flamingo. Al Freeman, the Sands publicist, saw an opportunity: world leaders Dwight Eisenhower and Nikita Khrushchev were scheduled to hold a summit later that year, so why not stage a summit of the world's entertainment leaders?

The idea was that the five would rotate through the Copa Room individually during filming. Instead, they started appearing together, and the shows became an unprecedented spectacle. They were supposed to run three weeks. They ran five. Hollywood came to watch — Lucille Ball, Jack Benny, Bob Hope. And Senator John F. Kennedy showed up, a presidential candidate courting Sinatra’s support and star power. It was during those weeks at the Sands that Kennedy reportedly first met Judith Campbell, who became his lover — and who was also involved with Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana.

The Summit essentially invented what we now think of as the Las Vegas residency: a sustained run by a major act that becomes an event in itself, drawing audiences specifically to the city. Every modern residency on the Strip — from Celine Dion to Adele — descends in some way from those five weeks at the Sands in 1960.

After the Summit

Sinatra's own relationship with the Sands ended badly. In 1966, Howard Hughes had arrived in Las Vegas and begun a buying spree that would reshape the entire Strip — starting with the Desert Inn, then the Sands, and eventually half a dozen more properties. When Hughes's management cut Sinatra's line of credit at the Sands, Sinatra confronted casino executive Carl Cohen. It ended with Cohen punching Sinatra. Ol' Blue Eyes left for Caesars Palace and never returned.

Sinatra announced his retirement in 1971, but came back. He continued performing in Las Vegas for another two decades — at Caesars, then at the Golden Nugget after signing with Steve Wynn. Martin and Davis reunited with Sinatra for a "Together Again" tour in 1988, though Martin dropped out after just a few performances. His son Dean-Paul had died in a plane crash the year before, and the loss had broken something in him. His last Las Vegas performance was at Bally's in 1990. The Rat Pack as a performing unit was finished, but as a brand, an idea, a shorthand for a certain kind of Las Vegas — it never went away.

The Other Side of the Strip

The Rat Pack mythology is glamorous. But the Las Vegas they performed in was a segregated city, and the contrast between the stage and the street is part of the story.

In the 1950s, Black entertainers could headline Strip showrooms but were barred from the hotels’ restaurants, pools, and guest rooms. After the show, they crossed to the Westside — Las Vegas’s Black neighborhood — to sleep in boarding houses. Davis was the most visible example of this contradiction: one of the most celebrated performers in the world, entering through the kitchen of the hotel where his name was on the marquee.

Sinatra pushed back against this, vocally and publicly. He claimed on a live album to have helped desegregate Las Vegas by insisting that African American entertainers be allowed to stay where they performed. How much credit he personally deserves is debated by historians — the desegregation of Las Vegas was a longer and more complicated process than any one person’s intervention. But Sinatra’s willingness to use his leverage at the Sands on behalf of Davis and other Black performers was real, and it mattered in an era when few white entertainers with that kind of power were willing to spend it.

The Rat Pack’s Legacy

The Sands is gone. The Venetian stands where it was. The Copa Room exists only in photographs and recordings. But the model the Rat Pack built — celebrity as destination, entertainment as the reason to come to Las Vegas rather than just something to do between hands of blackjack — is still the operating logic of the Strip.

Before the Summit at the Sands, Las Vegas was a gambling town with entertainment. After it, Las Vegas was an entertainment capital that also had casinos. That shift shaped everything that followed: the mega-resorts, the production shows, the modern residencies, the city’s identity as a place where the biggest names in the world come to perform. The Rat Pack didn’t just play Las Vegas. They helped create the version of it that still exists.