I have this image fixed in my mind: Susanne Forestieri is sitting on a small couch in the living room of her Downtown home. It's a Monday afternoon, summer 2017. The sun is pushing at the windows and the artist, battling a rare form of cancer at 72, is resting leisurely on a bright, multicolored blanket discussing art, friends, and current events as if nothing tragic is happening here.

She's between chemo treatments, feeling better, and preparing for upcoming exhibits. Her spirits are good and, of course, she is still painting, still searching for truth and beauty through her art.

"The biggest surprise to me is that making really good art doesn’t get any easier with time and age," she says. "Each work is a struggle to bring to life. On the up side there is great joy and satisfaction when you succeed."

I listen to her talk in the quiet of the afternoon. She's the strong, observant, perceptive, and hilarious woman I'd always known. Weakness and exhaustion would overwhelm her at times, but even at her worst, the artist spoke of pain in the way she spoke of everything — honestly, openly, intellectually, and with a bit of humor.

She was that same person earlier this month after returning from New York, where she had been receiving treatment at Memorial Sloan Kettering and was finally told that nothing more could be done. Back in Las Vegas, she continued drawing and spending time with friends and family.

On Monday, shortly after 7 p.m., Susanne Forestieri died at Nathan Adelson Hospice after her health took a sudden sharp turn. She was 73.

"She didn't want to suffer anymore," says daughter Gina Forestieri. "She was definitely at peace with it. She lived doing what she loved. But once she couldn't do art, she was ready to go."

The loss of of Forestieri, an exceptional painter, art advocate, community supporter, teacher, and good friend to so many, has been hard to accept. Forestieri was always involved, always out there, always caring. Most of all, she was always, always painting, pushing herself forward, though she'd mastered her skill so long ago.

"You need a lot of courage to keep going as an artist, because the kind of worldly rewards are not always there," she said that afternoon in her living room.

"I've always had classical taste in art, and although I appreciate modern art and other periods, I always come back to something I define as classical, even if it's abstract. My strength is my enormous expressiveness and painterly touch."

I look at her surrounded by the colors of the blanket on the sofa that day, and then to her walls. Her home is a museum, the life of an artist in oils, charcoal, graphite, and watercolor. There are representational and traditional works, abstracts, modernist paintings, and experimental works. More recently, she's created rich, lush painterly works of the flowers her friends and family had been bringing to her. She'd always say, "Cancer is a terrible way to learn how much you are loved."

No matter the subject — portraits, landscapes, moments from everyday life, abstracts — her classical training, impeccable skill, and deep knowledge of light and color created a life and a depth in her work.

She brought this with her to Las Vegas three decades ago, leaving Manhattan, where she'd had grown up enriched in arts, dance and intellectual pursuits and attended Art Students League in New York City, beginning her career in the late 1960s.

She brought her family out west, wanting to be closer to her mother, who was living in Las Vegas. Here, she received her BFA, her MFA, and a Masters of Arts degree in education. She received a 1996 National Endowment for the Arts fellowship in painting, tackled public commissions, and was an original and longtime member of the nonprofit Contemporary Arts Center.

Her paintings and drawings, hundreds of them, live in homes throughout the Las Vegas Valley, and in private and public collections. Her legacy is everywhere here. She taught at Imprints Academy, at UNLV, in workshops, and to children and adults at her home studio, all the while pursuing her studio work and exhibiting. It was always fascinating to see her work among the contemporary, experimental, and conceptual work by artists within the city.

"Susanne was producing tremendously accomplished work, but she was making paintings at a time when paintings are not considered cutting-edge. In contrast to other artists, she didn't want to make statements — she wanted beauty," says Dawn-Michelle Baude, art writer and friend of the artist. "That woman could discuss Greek Socratic philosophy, Shakespeare's history plays, and critiques of capitalism. She read literature, but also in many other areas. She never paraded her learnedness, but it seeped into her conversation and influenced her art.”

Dana Satterwhite, former owner of TastySpace Gallery and friend of Forestieri, describes her love for life: "She had an inexhaustible spirit, was a fountain of wisdom, and remained a creator to the core, practicing and teaching drawing and painting, playing piano, writing, and, in her earlier years, reveling in the art of belly dance.

"She often said she didn’t like to show work that was of a personal nature because she feared her audience wouldn’t be able to connect with something so close to her. And then, of course, she found these were the works with which viewers were able to connect the most."

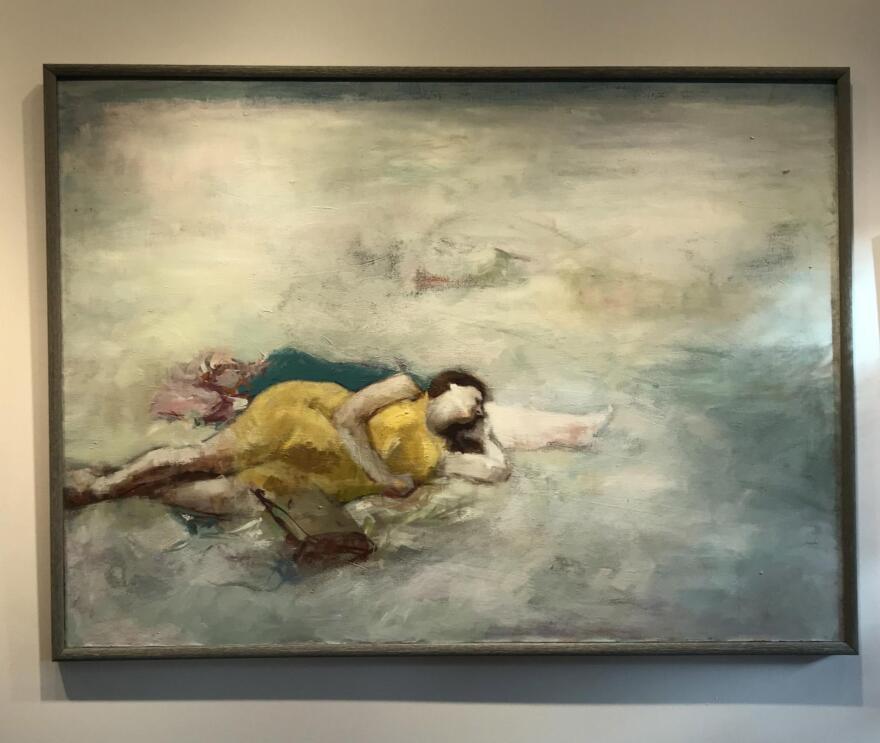

Forestieri's last solo show in Las Vegas, Reminiscenes: Susanne Forestieri Friends, Family, Showgirls, and Color, at Nevada Humanities last spring, featured this personal work through selections of figurative and representational works she made in 1970s and onward — paintings of family and friends at the beach, at home, in conversation, dancing, dressing, posing, talking on the phone, or sitting at a cafe.

"She really wanted to share the scope of her work of her family," says artist Bobbie Ann Howell, program director at Nevada Humanities. "She was sick, going through chemo, but determined to do it. It's hard when you paint every day and then you're too weak to pick up a brush, because your mind is still thinking about your work. And you never stop thinking about your work."

Forestieri was 70 when her work took an entirely different direction: She had begun dating again, rediscovering her sexuality and painting her intimate moments with lovers.

This was when she was introduced to Yasmina Chavez, a media artist in Las Vegas who was in her first semester of grad school at Alfred University in Upstate New York. Foriestieri had been looking for someone to talk about her new work with. Dana Satterwhite, sensing the two of them were of like minds, introduced them over Skype and they became fast friends.

"She had been doing personal work, portraits of family and friends," Chavez says. "But this was a whole new realm, it was about sexuality, dating, and desire. It was something she jumped into fearlessly. She was exploring this for herself. She was so open about it, so vulnerable; that's what made me fall in love with her."

The works, some of which hung in Forestieri's home, have never been exhibited, which is unfortunate. "The honesty is the biggest quality," Chavez says of one of the works in the series. "When you're intimate with someone like that, it's like the whole world gets lost around your bodies. It disappears and you're in this space together."

It was what Forestieri represented about life, the human condition, being a woman and an artist through multiple stages of life that stood out most for Chavez. "I always had this assumption that women who are 50 or 60 are done (with certain things). I don't know if it's cultural or society, but desire I thought died off when you reach later years and then you found a sort of peace.

"And here is Suzanne showing this life force within us. And it never stopped. She proved me wrong. She empowered herself. It was a huge revelation. It inspired me to fully live, to embrace my womanhood, to be this woman with desires, not just about sex, but companionship, love, freedom, expression."

And Forestieri was all the way in, always ready to explore creativity.

"I asked, 'How do you feel about getting naked and being covered in mud and standing in the sun until it goes down for an hour or so.' She said, "'Okay. I got a place!'"

The two headed to a summer house owned by a friend of Forestieri's in Tecopa, California, where, for a piece of video art, Forestieri was covered with bentonite clay and sat with the mud cracking as the sun went down, an event she later documented on a blog post. Because six months after Tecopa, Forestieri had been diagnosed with cancer.

"When I saw the Warm Bodies video I was shocked by the final scene," Forestieri wrote . "Seen from the back, I’m being led away to rinse off, but what I saw in my mind was the end of a life — a cinematic riding into the sunset. I was so weak, a friend had to hold me up, and the fading light gave the scene a poignant feel. It turned out to be prescient since I received my cancer diagnosis six months later and was sure I would die soon. After surgery and six months of chemo-therapy I was too weak to paint, but I could feel my soul dying, so I resumed painting, if only for an hour a day.

In the end, when she could no longer paint, she drew.

"She was going back to her roots," says artist and longtime friend Stewart Freshwater, whose life drawing workshop at the Arts Factory Foriestieri was attending in recent weeks. "It was so good to see her. She'd carry things up that flight of stairs. Her friend Beth Brooks McCall was with her and would help her out."

Knowing that Forestieri was still out there doing this in her final weeks was of no surprise to anyone who knew her.

"Art was her love," Chavez says. The two spent time together at the hospice during Foriestieri's final days. "When she was first diagnosed with chemo, she started making weavings. She made looms out of cardboard in different shapes and sizes and made little sculptural tapestries. She was a life force. She never stopped making art."

In addition to daughter Gina Forestieri, she is survived by her mother, Doris Kougut; son, Peter Anastasopoulos; grandson Edward Anastasopoulos, and several extended family members and friends. Though no services are scheduled, a private gathering is being planned.