What we talk about when we talk about growth. (Hint: the answer isn’t prosperity for workers)

Jeb Bush got a bad rap. Sort of.

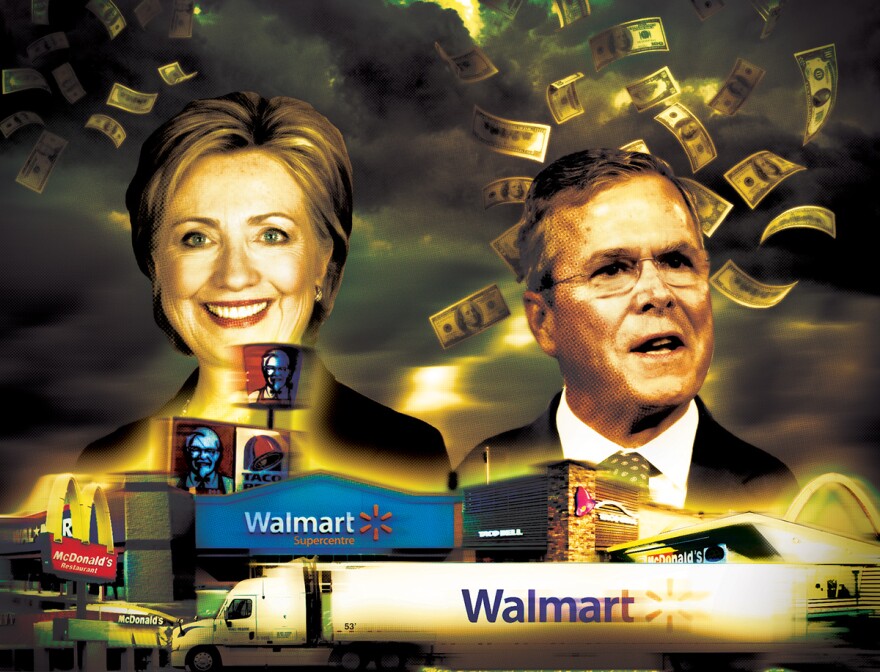

Critics pounced last month when Bush declared that “people need to work longer hours.” Progressive think tanks dusted off studies showing Americans already work more hours and take fewer vacations than anyone in the industrialized world. Democrats mocked Bush as a Romney redux, another out-of-touch rich Republican. U.S. workers “don’t need a lecture,” Hillary Clinton lectured. “They need a raise.”

Clinton’s right. Workers do need a raise, especially here in Nevada, where retail, food service and clerical jobs are simultaneously among the most common and the poorest paying.

Bush is also right, or at least partly right: Many people who are working part-time would prefer to work full-time, especially in those aforementioned sectors that are so super-sized here in Nevada.

But from Bush and Clinton and the rest of the presidential candidates parachuting into Nevada, all the way down to aspiring career politicians seeking congressional seats, to would-be wheeler-dealers running for the state Legislature, mainstream political rhetoric about jobs and the economy comes with a baked-in blind spot.

With the possible exception of a woman whose husband was president, perhaps no one is better suited to reflect the political establishment’s conventional economic thinking than a guy whose brother and father were both president. So let’s start with Bush chiding you for being a slacker.

It was only after the fact, when he was backtracking, that Bush lamented — again, correctly — the plight of the involuntary part-time employee. His original point was altogether different. Specifically, Bush said people need to work longer hours to help the U.S. achieve his goal of 4 percent annual economic growth.

Unlike abortion, voter ID laws or Season 5 of Game of Thrones, almost all Americans are in complete agreement on economic growth: They’re for it. The assumption, the widely held “common sense,” is that when the economy grows, everybody benefits. So politicians of both parties promise to “grow the economy.”

Growth can lead to more and better jobs and to higher pay in existing ones. But it doesn’t always, because there’s another factor that has a lot more to do with your job, a factor that U.S. politicians address much less frequently than growth, if they address it at all. Let’s say the U.S. economy grows at the expected 2 percent rate this year, from $17.7 trillion to $18 trillion. No wait! Let’s pretend Jeb is already president and because he’s so smart the economy will grow at 4 percent, from $17.7 trillion to $18.4 trillion. Whichever, the ground-level issue that matters to wage-earners is not how much the economy grows, but how those trillions of dollars are distributed.

For instance, more than one trillion of those American dollars are absolutely, positively not going to you — or any other American wage-earner. U.S. corporations are on pace to spend $1.2 trillion, an amount roughly equal to 7 percent of the economy, not to create new jobs or raise wages or develop new products and technologies, but to buy back their own corporate stock.

When corporations repurchase their own shares, they take shares off the market. That (usually) raises the price of remaining shares, to the benefit of the wealthiest investors, whose ownership of U.S. stock is of course inordinately large. Apple has been leading the buyback frenzy. “Activist” investor and occasional Las Vegan Carl Icahn has relentlessly bullied Apple into bigger and bigger buybacks — some $200 billion over a three-year period that will not be spent to build a phone that can hold a charge or increase salaries at the Genius Bar or in Chinese sweatshops, but to further enrich people like Icahn.

CEO pay packages are almost always tied to share price. So even as more and more working Americans are getting sucked deeper into financial black holes, CEO compensations have gone supernova, thanks in large part to stock prices manipulated by buybacks.

Walmart, Yum Brands (KFC, Taco Bell etc.) and McDonald’s, the nation’s three largest private-sector employers, pay poorly, provide shoddy or no benefits and love “flexible” scheduling — the hallmark of those involuntary part-time jobs that Jeb Bush wants to make full-time. Yet even as the economy has struggled to rebound from the worst collapse of most of our lifetimes, there has still been enough economic growth to allow those companies to spend billions — not to give workers a raise, or roll back reliance on low-cost flex labor, but to buy back their own stock.

Stock buybacks are just one way that 21st-century economic growth fails to get distributed throughout the general population and show up in your paycheck. We live, after all, in a world where banks are bailed out and people aren’t; where wages are taxed much more heavily than investment earnings; where trust in the power of economic growth is so ingrained in public discourse that the word “distribution” is taboo and “redistribution” is nigh on treasonous; where “common sense” all but demands that government turn its back on the quaint 20th-century notion of helping people and instead focus instead on helping markets. (Nevada’s aggressive push to transfer your tax dollars to private education companies, adopted by state government earlier this year, is almost a caricature of market idolatry.)

Nevada is rebounding, or so the governor says, and true enough, Nevada has experienced economic growth since bottoming out at the end of the last decade. Why, according to the Economic Policy Institute, the income of the richest 1 percent of Nevadans increased 40 percent from 2009 to 2012, and the incomes of everybody else … fell by 16 percent.

That disconnect between growth and distribution has not gone wholly unnoticed by politicians of both parties, who often as not vow to address it with … more growth.

For example, John Oceguera, a Las Vegas Democrat running for Congress, declared last month that “priority number one must be creating good-paying jobs that can support a family.” Priority number one will be achieved, Oceguera added, by “supporting the entrepreneurs and small businesses that power the engine of our economy,” i.e. helping the private sector grow some more.

As I reported in Desert Companion in June, at least one-third of the jobs Nevada already has fail to pay enough to support a family. That’s not a growth problem. Those jobs are projected to grow in larger numbers than any others well into the foreseeable future. A less growth-smitten political class might conclude raising pay in those jobs, not creating new ones, should be “priority number one.” Alas, that’s a distribution problem. And politicians generally don’t go around saying “priority number one” is wealth redistribution.

This is not to single out Oceguera. He’s echoing statements uttered every day by politicians from both parties in Nevada and nationwide.

And to be sure, from long-shots like Oceguera to Clinton the presumptive presidential nominee, Democratic politicians, following the lead of an awakened portion of the Democratic electorate, increasingly accompany their ubiquitous growth worship with support for other, presumably nice things, like a higher minimum wage or mandated sick leave. Perhaps no living Democrat was more enamored with the power of economic growth than Bill Clinton. Now his wife says we don’t need a growth economy, but “a growth and fairness economy.” She’s even complained about stock buybacks.

But it could prove tough for fairness to prevail against decades of an abiding faith in the power of economic growth, even among Democrats, and especially in Nevada.

From 2011 through their humiliating drubbing at the polls in 2014, the one economic idea that Nevada Democratic legislators touted more than any other was a tax credit for the film industry — a classic if not cliché manifestation of the belief that government’s role is to facilitate markets because that will lead to growth and … jobs, or something.

The tax credits were ultimately scaled back to help finance a much more massive example of government helping out the private sector in the name of growth. Every Democrat in the Legislature voted for the Tesla deal, a deal for which Nevada Democratic Party boss Harry Reid takes credit.

Democrats disavow so-called “trickle down” economics. But what exactly do film credits or the Tesla deal specifically, and the obsession with growth generally, reflect if not the belief that when government helps the private sector grow, prosperity will trickle down through the rest of the economy?

Or, as one critic put it:

“… some people continue to defend trickle-down theories, which assume that economic growth, encouraged by a free market, will inevitably succeed in bringing about greater justice and inclusiveness in the world. This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power and in the sacralized workings of the prevailing economic system. Meanwhile, the excluded are still waiting.”

It’s easier for the pope to denounce “free market” domination of democracies, the global economy, our identities and even our thoughts. He’s not on the ballot.

An argument can be made that it’s becoming somewhat easier for politicians, too, to challenge the market’s uncontested reign over, well, everything. But that assumes a mainstream political willingness to do anything of the sort.