A stalwart Nevada tradition, the Cowboy Poetry Gathering isn’t just a festival – it’s a chronicle of a changing sense of rural identity

Elko

You won’t find too many Las Vegans in Elko — the town of 20,000 residents in northeast Nevada is closer to Utah, Idaho and Oregon by a long shot — and the snowy peaks surrounding it are a reminder that we’re really not in the Mojave anymore. But at the beginning of every year, for the last 36 years, the population swells by a few thousand more: They come for the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering, an enduring Nevada tradition that draws ranchers, poets, and cattle-driving songsters, as well as a handful of city folk like me.

I am by no means a cowboy, or a poet, for that matter. I’m a city girl from Las Vegas (“You mean East L.A.?” someone teased, not unkindly, in Elko). It’s easy to feel like we’re not quite so rural West down here, with our just-barely-there inclusion in the state, like someone cut an extra-long piece of cake to sneak in another bite.

Still, the history of our city is part of a frontier tradition — a street named Rancho runs through the heart of town, and Vegas Vic and Vickie both sport Stetsons, after all. The history of the West, the good and the bad, is our history too. So it was in search of this that I packed my boots and made my way north.

“Gathering is a ranching term — you gather the cattle, that’s seasonal work,” says Kristin Windbigler, executive director of the Western Folklife Center, the organization behind the event. “It’s a really important part of how we think about ourselves.” As such, the weeklong jubilee takes place in winter, when there tends to be less ranch work for most.

People come from all over the world; I met a folk singer from Northern England, a Canadian cowboy, and even a few New Yorkers. The event is a celebration of Western storytelling, with movies and music, cooking workshops and square dancing — you won’t be able to do it all, but that’s maybe why so many return year after year.

At the bar on the first floor of the Western Folklife Center, the space fills up with broad-brimmed hats, and the first orders of beer start coming in just around 10 a.m. You might go from a thought-provoking panel on ranch management to a rollicking blues concert, followed by a workshop on hearty trail ride cooking. In the afternoons and evenings, impromptu jam sessions start up in the back of the room around the fireplace.

Naturally, the heart of the Gathering is the poetry. Cowboy poetry is a genre born out of the cattle-ranching operations of the American West, based in the oral tradition of campfire storytelling. The form tends toward tradition, with regular rhyme and meter. Themes center around Western life: Horses, hard work, and the simple life. The romance of the ranch is often tempered with wry humor.

In Nevada poet Waddie Mitchell’s “Evening Chat,” performed during the keynote, the speaker tells his young horse about the value of experience: “Sort of lets an older feller / Work at a slower pace / And still get as much accomplished / On account of fewer mistakes.”

The audience here is studded with Stetson silhouettes. Pearl snaps, leather boots, and vests abound. For those who wish, the convention center and surrounding venues have even more shopping opportunities, with ornately carved saddles, silverwork and Western art on display. I learned how to tie a silk wild rag, standard attire for the event, and learned that boots go inside your jeans.

RHYMES WITH REASON

The Gathering is also a reminder that the West isn’t a monolith. “We take our cues from the evolving American West,” says Windbigler. “We also take cues from our artists, what’s important to them, what they’re talking about.”

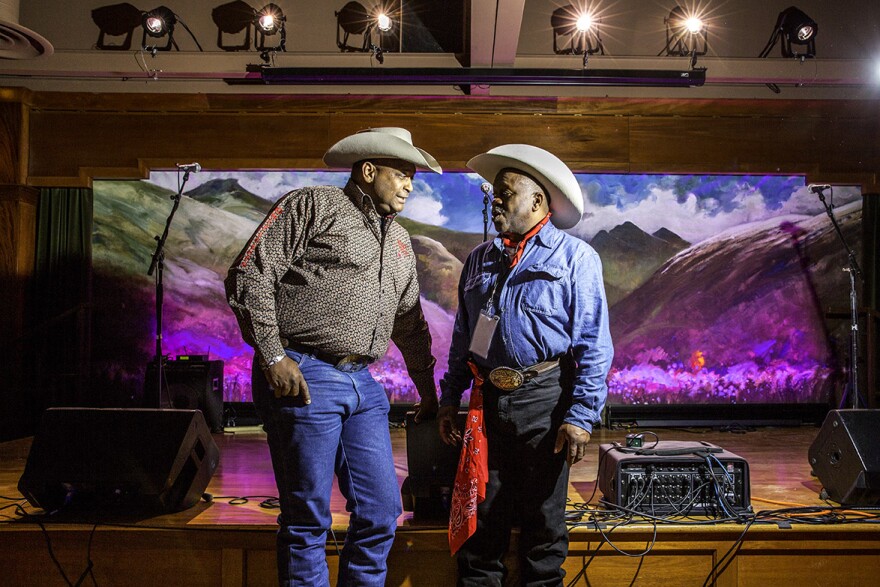

In that spirit, this year’s theme of “Black Cowboys” was particularly relevant, as the wild success of Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” in 2019 opened up a national conversation about the long and underrepresented history of black cowboys. Folks on Twitter might be familiar with the term “yee haw agenda,” coined by Bri Malandro, to describe the resurgence in cowboy aesthetics among black musicians and artists, including Solange, Megan Thee Stallion, and Lizzo.

“It’s been really interesting to see how deep the story has reverberated with the popular culture,” says Dom Flemons, whose 2018 Smithsonian Folkways album Black Cowboys was nominated for a Grammy. Flemons and his wife, Vania Kinard, were consultants for the Gathering, and curated an exhibit in the Western Folklife Center’s gallery that featured displays of black cowboy legends, a newly unearthed black cowboy comic strip from the 1950s called “The Chisholm Kid,” and modern-day portraits of Mississippi Delta cowboys by photographer Rory Doyle.

“Now is a time to repatriate this information back into the mainstream,” says Flemons, noting that segregation was partly to blame for the loss of black cowboy stories. He cites figures like rodeo legends Bill Pickett, who mentored Will Rogers, and Myrtis Dightman Sr., often called the “Jackie Robinson” of the rodeo — a living legend who joined the Gathering this year.

The point that both the Gathering and the “yee haw agenda” make is that black cowboys aren’t new. They’ve been around as long as there have been cowboys. One historian estimates that a quarter of all cowboys were black, and a third were non-white (case in point: the word “buckaroo” originates from the Spanish “vaquero”).

Hollywood’s whitewashed portrayal of the Wild West, with its blue-eyed deputies, papers over a much more complex history. “We kind of grew up with it, with Gunsmoke and Rawhide. There’s this whole romancing of the American West,” says Geralda Miller, a Reno-based historian and nonprofit executive who led several panels at this year’s Gathering.

Not only did popular culture downplay the presence and contributions of black cowboys, it also conveniently downplayed the racism. “Many people think that racism and segregation didn’t happen in the West, but it did,” Miller says. When logging companies moved to Oregon from the South, for example, they brought their policies with them, segregating the logging towns. And Nevada’s casinos, in an effort to cater to Southern customers, were segregated until well after the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964.

“Part of the way that each of these black cowboys survived was that they overcame these obstacles and built new lives for themselves,” Flemons says. “The album and the exhibit are reflections and manifestations of that sort of resilience moving forward.”

The racial politics of the West are still complicated, and still relevant. Something Miller said stuck with me: “African American or black history is not just my history, it is the history of America,” she said. “It’s the story of all of us, and how we have in this one land, the United States of America, grown and developed as a people, as Americans.”

SHARED WORK, SHARED RISK

Yes, if you were wondering, the vast majority of the faces at the Gathering were white. My photographer and I were among maybe half a dozen Asian Americans at the event — it took me a couple days to realize why the littlest children were staring at me, and why a woman at breakfast insisted we had met before.

But when I smiled at them, they grinned back. The welcome we received at the events was warm and real. A black cowboy I met who preferred to go unnamed said that he had actually been a little worried before coming, but was pleasantly surprised by how kind everyone was, and how eager they were to hear his stories.

Flemons surmises that it was the centrality of work in the West that laid the groundwork for progress. “Many of these black cowboys were exceptions to the rule because they were working people — there was connection through the pioneer spirit.”

It’s this sense of shared work and shared risk that young poet Clare McKay drew on when she recited a poem written through the eyes of a black cowboy: “As long as I’m breathing God’s fresh air and doing right / I figure it don’t matter much / whether my skin is dark or light.”

None of these truths negate the others. There’s no easy way to tie it up with a neat bow on top, because the experiences of race in the West are vast and varied — there is no one black cowboy experience.

And even though I thought I was coming to the Gathering with an open mind, I realized that I had underestimated the capacity for nuance in the rural political landscape. Though politics were rarely discussed, the conversations I overheard ran the gamut. I noticed just one red MAGA hat that week (perhaps on account of all the other elaborate headgear on display). On a walk from one side of town to the other, I only saw three campaign signs: A Trump banner, a Julian Castro poster, and a yard sign that read “Any Functioning Adult 2020.”

I asked Windbigler whether she’d seen any minds changed by the black cowboys exhibit and events. She hesitated. “I don’t want to call somebody out,” she said, but she had seen conversations online after the event that moved her. “The specificity of people’s own personal stories can still change other people’s minds about how they see something,” Windbigler said. “That means civility in discourse is still alive in this country — despite how people talk about how divisive everything has become.”

I wasn’t the only young person hooked on the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering. Windbigler says this year, anecdotally at least, there seemed to be more young attendees than ever. I think it has something to do with the way cowboy poetry feels like a rejection of the cynicism and snark that’s too often the currency of Twitter dialogue.

I felt it when the audience sighed around me while watching a newborn calf die in a documentary screening, and when workshop attendees murmured sympathy for a speaker’s murdered cattle “because a black man wasn’t supposed to own Herefords.” I felt it when amateur poets stepped up to the open mic events with nervous hands — and met enthusiastic applause. It was in the audience of hundreds singing a yodeling refrain (and myself joining in), in the laughter between our ungainly sets while I square danced for the first time in my life.

One midweek morning in Elko, I awoke to find our car covered in a layer of snow. “That’s why they gave us an ice scraper with the car rental,” I marveled. As I trotted around the car scraping ice off the windows, it occurred to me how much fun it was to be transported outside of my comfort zone, how privileged it was to feel mere amusement (and not fear worse), and how much work lay ahead of me to do this story justice. I stepped back to observe my progress — not perfect, but it would do. We’d be able to see out the windows. And the sun would thaw the rest in time.