With irresistible charm and high-level connections, Johnny Rosselli made things happen for the mob in Las Vegas

Through the annals of organized crime, documented for a century in newspapers, books, movies and cable TV shows, a handful of individuals have become household names: Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel, John Gotti. Even if you have little interest in the subject, these names register.

But there are scads of spellbinding stories featuring lesser-known figures. Perhaps the most fascinating of the lot is Johnny Rosselli. And, in a great bit of good fortune for us, Rosselli’s story is deeply entwined with Las Vegas.

Rosselli was involved in many major underworld episodes from the 1920s through the 1970s. As a young hoodlum, he worked for Capone in Chicago. Capone sent him to Los Angeles, where he hooked up with Tony Cornero, the King of the Western Rumrunners, and then set his sights on Hollywood, where he built relationships in the movie industry, orchestrated the mob’s takeover of craft unions and competed with Howard Hughes to bed the town’s most beautiful actresses.

He joined the Army during World War II but rather than serve his country overseas, he was convicted and imprisoned for labor racketeering. After three years behind bars, Rosselli returned to L.A., where he became embroiled in a battle for power between mob bosses Jack Dragna and Mickey Cohen.

In the early ’50s, Rosselli’s Hollywood ties were employed to help a singer named Frank Sinatra secure the lead role in From Here to Eternity. During this time, Rosselli turned his attention to gambling — legal and illegal. He traveled across the country and to Cuba, which crime bosses believed had even greater potential than Las Vegas.

After Fidel Castro seized Cuba, destroying the mob’s Caribbean cash cow, Rosselli took part in a CIA plot to assassinate the bearded revolutionary. He was not successful, obviously, but not for lack of trying.

Around this time, Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy was running for president, and when he paid a visit to Las Vegas, Rosselli was tapped to find a suitable female companion for the virile candidate. He delivered Judith Campbell (later Judith Exner), whom Rosselli had dated and whose affections would later be shared by Kennedy and Chicago mob boss Sam Giancana.

Campbell was not Rosselli’s only connection to JFK. There also was Marilyn Monroe, whom Rosselli had met in the late 1940s and who had an affair with Kennedy before her apparent suicide in 1962.

There’s also the widely disseminated theory that Rosselli was the second shooter in Dealey Plaza, but we’ll get to that later.

Rosselli’s story could have ended in the mid-1960s and still have been epic in scope. But one of his most important missions was still to come.

‘Charismatic character’

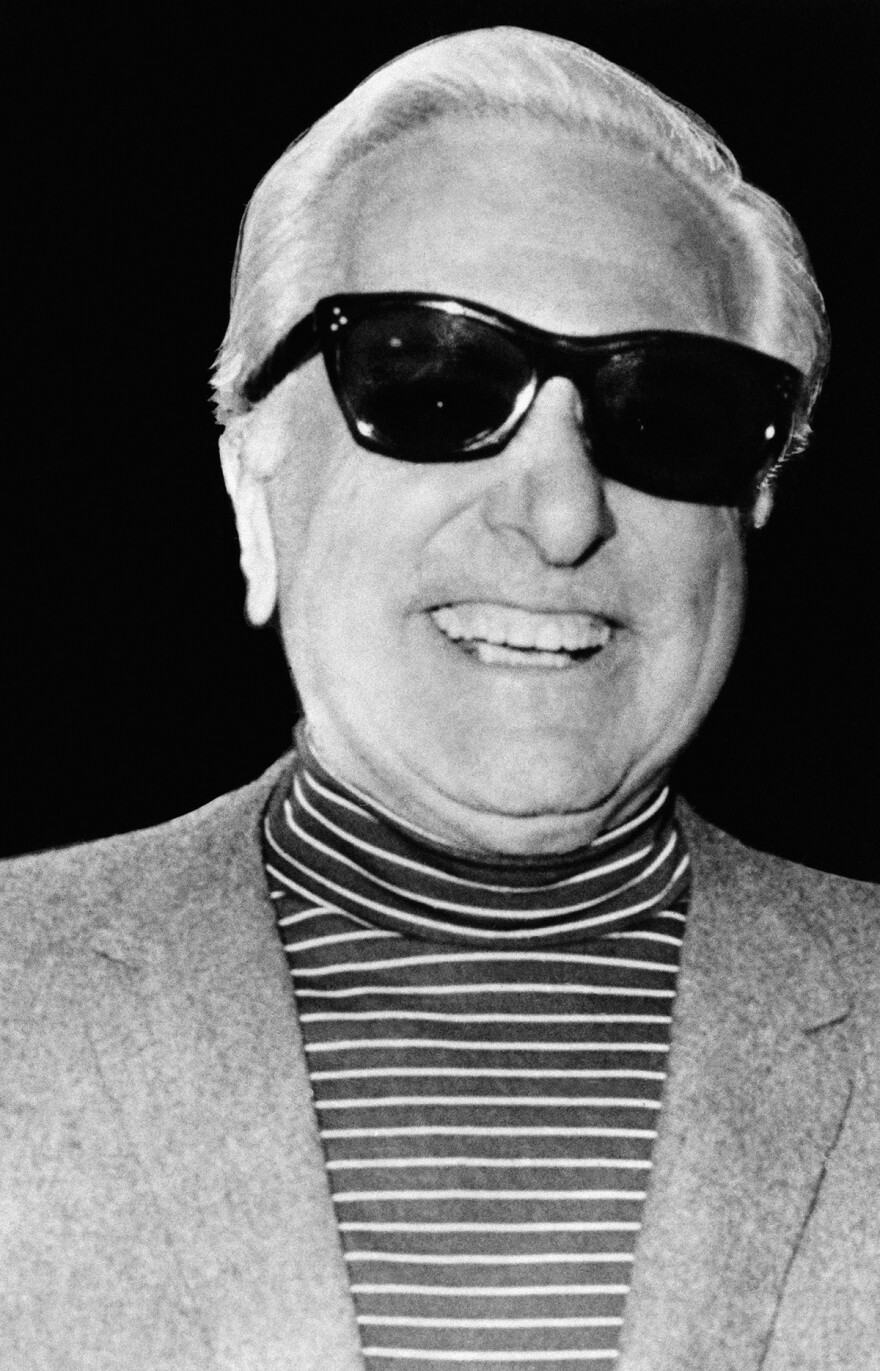

By all accounts, Rosselli was a good-looking, charming man. He had two nicknames: “Handsome Johnny” and the “Silver Fox.” “He was a very charismatic character,” says Peter Maheu, whose father, Bob, knew Rosselli well. “There’s something about people like that — when they walk into a room, everybody has to turn around and look at them. Johnny was one of those guys.” Maheu recalls Rosselli always being well put together. “He was impeccably dressed. I never saw him not dressed in expensive suits and beautiful ties.”

Bob Maheu threw lots of lavish parties that brought together politicians, business tycoons and movie moguls. “My dad had one of his famous clambakes and Johnny was there,” Peter Maheu says. “The only way to really explain Johnny is that he sucked the air out of the room when he walked into it. He was so striking.”

Casino industry veteran Bernie Sindler has similar memories of Rosselli, whom he knew well. They lived for a time in the same posh apartment complex in Los Angeles. “I used to have dinner with him at least once a week,” Sindler says. “He always had a smile on his face. He was good company, very funny.” Rosselli also was popular with women. “He had a lot of lady friends,” Sindler says. “They were movie stars and starlets. He was big with women.”

Sindler remembers the quiet power that Rosselli possessed. “He was absolutely the boss, and what he said, that’s what went down.”

Most of the time, anyway. Rosselli’s notable underworld achievements over the years were balanced by periodic errors in judgment.

For example, in 1966, Rosselli was in Las Vegas when he received word that Clark County Sheriff Ralph Lamb expected him, as an ex-felon, to check in with the authorities. Rosselli arrogantly ignored the directive. Lamb, who died this summer at age 88, decided the suave gangster needed a reminder of who was in charge in Las Vegas. He found Rosselli having lunch at the Desert Inn, yanked him over the table and slapped him around. Then, just to make sure Rosselli got the message, Lamb escorted him Downtown, where he was stripped and deloused.

An even dumber move was to get involved with a card-cheating scam at the Friars Club in Beverly Hills.

In the mid-’60s, Rosselli was a regular at the exclusive social club. One of his friends there was Maury Friedman, an owner of the Frontier hotel-casino in Las Vegas. Friedman often played gin at the club alongside Hollywood aristocrats such as actor Phil Silvers and singer Tony Martin, as well as card sharps with underworld connections. Friedman gradually raised the stakes in the casual games, with thousands of dollars on the table at any one time. Losses for some players amounted to hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Little did the “pigeons” know that Friedman was cheating them.

“Peepholes were drilled in the ceiling of the Friars Club, and a man posted in the rafters was reading the cards of the well-heeled Friars,” according to All American Mafioso, the Rosselli biography by Charles Rappleye and Ed Becker. “Signals were conveyed to the hustlers via a tiny radio transmitter strapped to the card cheat’s midsection. If the game involved two-man teams, the hustler with the receiver would relay information through an elaborate voice code. A word or phrase beginning with the letter A meant to hold kings, B meant queens, C, jacks, and so on.” Rosselli rarely played gin, but when he learned about the scheme he demanded a cut of the winnings, to which Friedman agreed.

In 1967, the FBI caught wind of the scam and raided the Friars Club. They seized the electronic equipment hidden in the rafters and convened a grand jury. Two months later, Rosselli was one of six men indicted.

Rosselli worked the angles, from calling for a hit on one of the witnesses to talking with high-ranking friends in Washington, D.C., to try to quash the case. It didn’t work. After a complicated, six-month trial, Rosselli was convicted on December 2, 1968. Friends appealed to U.S. District Judge William Gray to give Rosselli a lenient sentence based on his service to his country. Gray wasn’t impressed. “I am just not able to conclude that Mr. Rosselli is entitled to brownie points for having tried to assassinate Fidel Castro,” he said, and handed him a five-year sentence.

He served two years, nine months.

Sindler recalls that he was offered the chance to join Friedman’s cheating scheme. But he checked with his longtime mentor, Meyer Lansky, who advised him against it. “Too many people knew about it, and sooner or later they were going to get nailed.”

Misspent youth

Filippo Sacco was born on July 4, 1905, in Esperia, Italy. His family emigrated to the United States in 1911 and settled in Boston. As a teenager in hardscrabble East Boston, Sacco hung out with street gangs and got involved with criminal rackets.

In 1922, at age 17, Sacco was busted twice for dealing drugs. He made bail and skipped town. Sacco hooked up with bootleggers in New York, where he gained a reputation as a tough customer. Soon he was on his way to Chicago, recruited to work for an up-and-coming mobster named Al Capone. While helping Capone fend off rival bootleggers, Sacco built friendships that would serve him well for decades. He also adopted the alias by which he would be known the rest of his life: Johnny Rosselli.

The strength of the Capone organization was not Big Al himself, but the coterie of loyal lieutenants he assembled. Long after Capone found himself going crazy in Alcatraz, men such as Jake Guzik, Murray “Curly” Humphreys, Paul Ricca, Tony Accardo, Frank Nitti and, eventually, Rosselli built the smartest and most effective criminal enterprise in mob history.

For Rosselli, however, his apprenticeship in Chicago was cut short when Capone dispatched him to Los Angeles in 1924. He immersed himself in the Italian community of L.A., and eventually hooked up with Tony Cornero, Southern California’s biggest bootlegger. During Prohibition, Cornero used freighters to bring in illegal liquor from Canada and Mexico. Rosselli was a key henchman as Cornero battled with pirates intent on hijacking his high-quality hooch.

When the law caught up with Cornero in 1927, Rosselli renewed his connections in Chicago, only to witness Capone’s downfall, largely the result of his front-page antics and above-the-law attitude. “Rosselli took the brief episode to heart, and throughout his life shunned Capone’s flamboyant manner and lust for the spotlight,” his biographers write.

Returning to L.A., Rosselli partnered with another young Mafia boss, Jack Dragna, who, like Capone, was intent on usurping the old guard. Although police records don’t reflect it, Rosselli actively participated in the violent mob turf wars of the era, employing enforcers such as Frank Bompensiero and Jimmy Fratianno to eliminate competitors.

The man in Vegas

When Sam Giancana took over day-to-day control of the Chicago Outfit in 1957, he sent Rosselli to Las Vegas. Rosselli had tinkered in Las Vegas before, but now he would be Chicago’s main man there, replacing Marshall Caifano, who used intimidation and violence to get his way. Rosselli would get more done with charm and guile.

Rosselli’s first Las Vegas deal resulted in the Tropicana Hotel, which had hidden mob-ownership interests from New York (Frank Costello), Miami (Meyer Lansky) and New Orleans (Carlos Marcello). Rosselli would benefit from the deal by owning the parking and gift shop franchises, and booking the entertainment.

The Tropicana could have been a huge cash cow for everybody involved, but three weeks after it opened, Costello was shot in an assassination attempt orchestrated by power-hungry underboss Vito Genovese. Costello survived: The assassin’s bullet only grazed his temple. But while doctors attended to Costello’s wound, police officers went through his pockets and found a slip of paper that broke down the Tropicana skim.

Although the Tropicana skim soured for a time, Rosselli’s influence in Las Vegas increased. Through his hidden interest in Monte Prosser Productions, he controlled much of the entertainment booking in town. He arranged casino loans provided by the Teamsters Union’s Central States Pension Fund. He orchestrated the Cleveland-Chicago mob takeover of the Stardust Hotel after its founder, Rosselli’s old bootlegging partner Tony Cornero, died before it was finished. He even profited from the ice-machine business on the Strip.

Las Vegas was an “open city,” in mob parlance, meaning no single syndicate could gain a stranglehold on the Strip. But no matter who was involved, Rosselli coordinated everything that happened. In their 1963 exposé of the mob’s influence in Las Vegas, The Green Felt Jungle, Ovid Demaris and Ed Reid painted a colorful picture of Rosselli:

“Rosselli is definitely of the new school — sharp silk suits, diamond accessories, swanky apartment, busty showgirls in full-length minks, big Cadillac, gourmet taste, sportsman golfer — the best of everything in the best of all possible worlds. . . . Rosselli spends his leisure hours (that is, all the waking hours of his day) at the Desert Inn Country Club. He has breakfast there in the morning, seated at a table overlooking the 18th green. Between golf rounds, meals, steam baths, shaves and trims, Twisting, romancing and drinking, there is time for little private conferences at his favorite table with people seeking his counsel or friendship. It may be a newsman, a local politician, a casino owner, a prostitute, a famous entertainer, a deputy sheriff, a U.S. senator, or the governor of Nevada.”

Helping Hughes

The reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes moved to Las Vegas on November 27, 1966, and took up residence in the penthouse suites on the ninth floor of the Desert Inn. It was supposed to be temporary, but as the holidays approached, Hughes gave no indication that he planned to relocate. This didn’t sit well with Desert Inn boss Moe Dalitz, who had high-rollers slated for those suites during New Year’s. Hughes undoubtedly had more money than those high-rollers, but he wasn’t gambling any of it.

Hughes’ right-hand man, Bob Maheu, was in a tough spot. With Dalitz threatening to physically remove Hughes, Maheu turned to his old Cuba accomplice for help. Hughes, familiar with Rosselli from his Hollywood days, approved. “Rosselli was like a key to the city, the ultimate mob fixer in the desert,” Maheu wrote in his memoir, Next to Hughes.

First, Rosselli — supported by a call from Teamsters Union President Jimmy Hoffa — persuaded Dalitz not to evict Hughes. Then he served as a key player in the negotiations for Hughes to buy the Strip resort. For his services, Rosselli received a fee of $50,000.

The Hughes buying spree coincided with Rosselli’s Friars Club troubles, and he was frantic in his efforts to avoid going to prison. Rosselli wanted Maheu to appoint him manager of the Desert Inn casino, but Maheu adamantly opposed the idea. “He came back after we got possession of the hotel and he wanted to run the casino,” Peter Maheu says. “My dad got into a heated argument with Johnny. Dad said he wasn’t going to have anything to do with the casino.”

Despite that dustup, Rosselli also helped engineer Hughes’ purchases of the Sands and Frontier hotels. For the Sands deal, Rosselli received a $45,000 fee. The Frontier was different: Instead of a fee, Rosselli got the lease for the hotel’s gift shop, which netted him about $60,000 per year for the rest of his life.

As the mob’s point man in Las Vegas, Rosselli was involved in all kinds of behind-the-scenes activity. Before Hughes purchased the Silver Slipper casino, it was owned by Shelby Williams and Jack Shapiro, the latter of whom was tied to the Detroit Mafia. Bernie Sindler says he was approached to buy a piece of the Slipper.

“They came to me one day and wanted to see me. They said, we want you to buy 3 percent of the Silver Slipper for $30,000. But the deal was this: You have to give one-third of it to Johnny Rosselli. He’s going to be your partner. You are going to put up all the money and he’s not going to give you any money.” Sindler says the reasoning was that Rosselli was close to Maheu, who could be influential in causing Hughes to buy the Silver Slipper. “It will be done at a good number and you’ll make a lot of money,” Sindler was told. “But Rosselli is going to get a third of it.”

Sure enough, Hughes bought the Silver Slipper, netting Sindler a healthy $231,000. But now he had to figure out how to give Rosselli one-third of the proceeds without drawing any law enforcement attention.

“I was on the radar with the FBI all the time,” Sindler says. “They wanted me to be an informant and I wouldn’t do it. So, how am I going to give Rosselli $77,000 without any trace of anything, no banks, no nothing?”

Sindler figured it out. He happened to be a very good — and lucky — gin rummy player, and he had stashed his winnings in shoeboxes in his closet. He paid Rosselli his share out of those shoeboxes.

“I gave him his money, we shook hands, he went his way and I went my way,” Sindler says.

Star witness

After his release from prison in 1973, Rosselli moved to Miami, ostensibly retired, though he kept his eyes open for business opportunities to break up the monotony of his days by the pool. But he spent some of his time testifying before congressional committees.

In 1974, Rosselli appeared before the Watergate Committee, which wanted him to connect President Richard Nixon to the Castro assassination plot. Rosselli could not or would not confirm what Nixon knew.

In 1975, he was called by the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, known as the Church Committee after its chairman, Sen. Frank Church of Idaho. The committee wanted to know more about the plot to kill Castro. Rosselli was more helpful this time, in part because so much about the Castro assassination plot was already common knowledge. As he described the Cuba operation in detail, Rosselli kept the committee members on the edge of their seats. Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona interrupted the narrative to ask Rosselli a question:

“Mr. Rosselli, we’ve had CIA agents, we’ve had FBI agents, we’ve had other members of the government here, and all of them came in with their notes and files, and they referred to them in answering our questions, and it’s remarkable to me how your testimony dovetails with theirs. Tell me, Mr. Rosselli, during the time that all this was going on, were you taking notes?” Rosselli famously replied, “Senator, in my business, we don’t take notes.”

The following year, the Church Committee called Rosselli again, this time to probe what he knew about the Kennedy assassination. But unlike his voluble testimony on the Castro plot, he didn’t have much to say about Kennedy.

As the investigations were unfolding, Rosselli’s underworld friends warned him more than once that his life was in danger. After all, Sam Giancana and Jimmy Hoffa both had been rubbed out in 1975, at least in part because of concerns that they were talking too much. Rosselli routinely dismissed the warnings.

That carefree attitude was misguided. On the afternoon of July 28, 1976, he left the house he shared with his sister, Edith Daigle, and drove away in his Chevy Impala. She never saw him again. Two days later, Edith’s husband, Joe, found Rosselli’s car at Miami International Airport.

On August 7, Rosselli’s body surfaced. It had been dismembered and stuffed into a 55-gallon drum, which fishermen found floating in Miami’s Dumfoundling Bay. Authorities believe Rosselli’s killers did not intend for his body to ever be found. The 71-year-old had been shot and suffocated, and his legs were cut off.

“The drum was sliced with a series of gashes to let water in and air out, then wrapped in 20 feet of heavy two-inch-link chain for ballast, and sunk in 28 feet of water,” his biographers write. But “gases trapped inside the decomposing body had floated the drum with just enough buoyancy to bring it to the surface.”

Nobody was ever arrested for Rosselli’s murder, though it was widely speculated that the Chicago Outfit or Tampa Mafia boss Santo Trafficante Jr. — or the two in collaboration — were responsible. Whatever additional information Rosselli might have been willing to share with the authorities — which may have been nothing much at all — went with him as that 55-gallon drum sunk beneath the water.

Kennedy conspiracy

Johnny Rosselli’s story parallels the rise and fall of organized crime in America, and he had a part to play in many of the major plotlines. But there’s one tale that, if true, would elevate Rosselli to the top shelf of hoodlum history.

The Kennedy assassination is a breeding ground for conspiracy theories. With so much circumstantial evidence to sift through, it is rich territory for those who can’t accept that lowly Lee Harvey Oswald single-handedly brought down the president of the United States.

The CIA did it. The KGB did it. The Cubans did it. The Mafia did it. Even Vice President Lyndon Johnson might have had a hand in it. The lawyer and investigator Vincent Bugliosi said conspiracy theorists had accused 42 groups, 82 assassins and 214 people of killing Kennedy. One of the alleged assassins: Johnny Rosselli.

As the story goes, Rosselli was hiding in a storm drain beneath Elm Street when the Kennedy motorcade rolled into view. He allegedly had a clear shot at the president and took it.

The story, as fantastical as it seems, has been repeated by more than one source, including Bill Bonanno, son of New York Mafia boss Joe Bonanno, in his 1999 memoir, Bound by Honor. Bonanno claimed Rosselli told him about it while they were briefly in prison together.

But the Rosselli assassination theory does not hold up to scrutiny. The journalist Gus Russo has spent the better part of his long career researching the Kennedy assassination, and unlike most conspiracy theorists, he’s done the work of interviewing hundreds of people in person to get their stories. “This is poppycock,” Russo says of the Rosselli connection. “Rosselli was sleeping in Vegas on the morning of the assassination. He was woken up with a phone call about it.”

Part two of the theory is that Rosselli was killed in 1976 to prevent him from revealing the mob’s role in JFK’s death. But Russo says this, too, is off base. It’s true that fellow mobsters killed Rosselli to shut him up, Russo says, but not about Kennedy. “They were concerned he was going to bring down Vegas,” Russo says. “Kennedy was ancient history. It was all about bringing down Vegas. Imagine if he had sung to the feds about the skim.” It turns out that by 1976, casino skimming was on its last legs, in the process of being rooted out by federal authorities bent on cleaning up Las Vegas. But mobsters pocketing big money from the skim at that time did not have the benefit of hindsight.

Buying lawmakers

There is one other oft-told tale concerning Johnny Rosselli that deserves mention despite a shortage of hard evidence.

You’ll recall that the Nevada Legislature legalized wide-open gambling in 1931. This came after the same Legislature rejected similar measures in 1925 and 1927 and didn’t even consider the notion in 1929. The conventional wisdom has been that the onset of the Great Depression changed the minds of Nevada lawmakers. But some authors contend that bribes had something to do with it as well.

In The Outfit: The Role of Chicago’s Underworld in the Shaping of Modern America, Gus Russo — the same author who debunks Rosselli’s role in the Kennedy assassination — gives credence to the story behind Nevada’s move to legalize gambling. “When state officials considered ways to rejuvenate the state’s stalled economy, they were aided in their discussion by Curly Humphreys and the Outfit, who were conveniently expanding their dog-racing ventures in the state. The relaxing of Nevada’s gambling laws ... was likely the result of graft dispensed by Johnny Rosselli and Curly Humphreys in 1931.”

Russo interviewed Irv Owen, a longtime friend of Humphreys, who told him emphatically that Humphreys and Rosselli “bribed the Nevada Legislature into legalizing gambling.”

“Las Vegas owes everything to Murray Humphreys,” Owen said.

Consider the historical implications if this is true. What Russo is saying, in effect, is that none other than Al Capone, the most notorious mobster in history, is responsible for the industry that transformed Nevada from desert backwater to international resort destination.

The story is not farfetched. After all, we know Capone was linked with Bill Graham and his Bank Club casino in Reno. We also know Humphreys was the Outfit’s financial mastermind, cooking up all kinds of clever money-making schemes. And we know Rosselli was Capone’s man in California. We also have the testimony of John Detra, whose father, Frank, opened the Pair-O-Dice Club in Las Vegas in 1930. In a 1999 interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal, John Detra said his father knew Capone and that the Chicago gangster gave him money to pass around to Nevada lawmakers to support gambling legalization.

Mob history can be difficult to pin down. As Rosselli explained to the Church Committee, mobsters don’t keep notes. But if Rosselli’s connection to gambling legalization is valid, this would link him directly to 1) the start of Nevada’s gambling industry, 2) the mob’s heyday on the Strip, and 3) Howard Hughes’ buyout of mob casino interests, which led to corporate control of the state’s largest industry.

The beginning, the middle and the end. The historical trifecta. Perhaps only the Silver Fox was savvy enough to pull off that trick.

Geoff Schumacher, director of content for the Mob Museum, is the author of Sun, Sin & Suburbia: The History of Modern Las Vegas, and Howard Hughes: Power, Paranoia & Palace Intrigue.