Talent? James Henninger scoffs at the idea. The secret to this painter’s growing profile: discipline, practice, work. And then more work

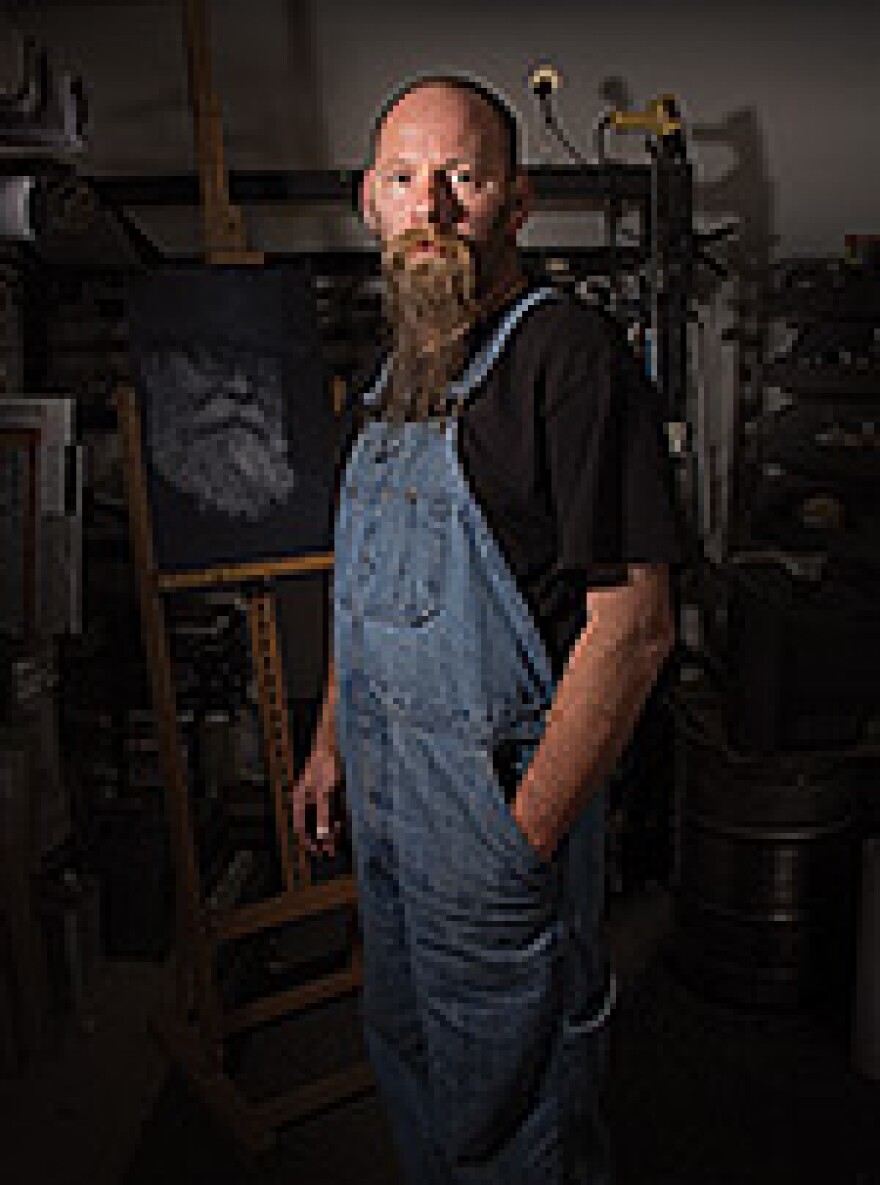

1. Go ahead, compliment artist James Henninger on his talent. That’s him, lounging on the afternoon patio at Bar + Bistro, bald guy with the groovy beard; don’t worry, he’s approachable despite those intense eyes. Stroll up and tell him you admire his sharply rendered portraits or photorealistic figure studies, almost always painted in monochromatic tones. (Actual viewer comment: “That’s a painting? It looks like a photo.”) Be sure to use that word, talent. He hears it a lot.

“Me, personally, I refuse to believe in it,” he might say. “There’s no talent involved. Zero talent.” He will say this with an air of complete frankness, despite the evidence of his own hands. “I have the ability to do it.”

Talk to Henninger long enough and he’ll say a few things that’ll have you shaking your head, about his work habits and productivity, his distant family, his single-mindedness, how he’s intimidated by color — but this is a genuine full-stop moment. Zero talent? Is that a put-on, a private joke? Who is this guy?

Good question. In a visual arts community that’s often preoccupied with questions of Vegas-ness — the relationship of the artist to the city, how to use Vegas in your art or be inspired by it (because who would squander this dazzling visual richness?) — he’s something of an anomaly. He doesn’t do Vegas, unless a dead-on portrait of Mayor Carolyn Goodman counts. No neon. No spectacle mentality. No interrogations of artifice vs. reality. And unlike most of the Arts District creatives who get mad ink in the weeklies, he doesn’t turn out academic-style work, inlaid with symbolism and pungent with cultural politics, or pop-art traipses along the high-low divide. “I love the figures, I love the face,” he says, and he can paint the hell out of a Morgan Freeman portrait or a naked torso. Looks like a photo, as you may have heard. So don’t go on about zero talent, dude.

But what he’s really getting at is a distinction between art as a consciously acquired skill, and art as something one is merely born with. Understandable, perhaps. Now 44, he says he left his estranged family at 15 “and never looked back,” along the way creating himself as a man and a self-taught artist (“I failed every art class I ever took”) through years of subsistence jobs and nonstop drawing and painting, until he became the professional artist he is. Given all that self-determining, it’s no surprise that he sticks gamely to his lack of faith in a quality as evanescent — and, therefore, possibly fleeting — as “talent.”

He tells a story about his father: “He did a little bit of drafting work,” Henninger says, his words hanging in the empty air of 303 North, his tiny gallery in the Arts Factory. “He wouldn’t really use a ruler, but he would make these ruler-straight lines. It was amazing. God, how do you do that? He said, ‘You draw a line long enough, you’ll eventually get good at it.’” But surely some talent is necessary to seal the deal? Nope. “That’s all it is. Practice, practice, practice.”

Just this once, don’t believe him.

2. Before his leaving at 15, there was his father’s ex-wife, who painted. “A lot of ethereal stuff — this was during the ’60s and ’70s,” Henninger says. In Southern California. “She did a lot of astrology-type stuff, constellations and so forth.” The subjects don’t matter; what mesmerized 5-year-old James was watching her create something out of nothing — art’s primal dynamic, after all. It was a life-shaping realization. “Since then I wanted to be as good as or better than her. That was one of my goals.”

Southern California in the late ’70s and early ’80s must’ve presented a rich zeitgeist from which an eager and developing young artist could draw: the waning of disco, the rise of West Coast punk, the first stirrings of West Coast hip-hop; the dawn of the Reagan era; the surf and skate scenes; Hollywood. But even then Henninger was stubbornly focused. He says almost none of that cultural tumult found its way into the pen-and-ink drawings he did then. Figures and faces, remember. And art classes? A waste. “I didn’t get what they were trying to do, or the rules, I never really understood,” he says. “So I always wanted to do my own thing.”

Two decades of mostly crappy jobs he’d take to keep himself in art supplies — “you name it, I’ve done it, from concrete work to drywall, construction and fast food, once” — found him a few years into his second stint in Las Vegas, taking stock of his life. Fifty hours a week working in a print shop, riding the bus a few hours every day. Frustrating, that. It left him too little time for art. He’d graduated from drawings to acrylics, and then to encaustic (pigments mixed with wax). His work had taken on new levels of photorealism — and, at last, salability. He began to make as much from selling paintings as from his full-time job. About a year ago, he called his girlfriend, Gia Iacuaniello, also an artist.

“I told her, ‘I’m gonna quit my job.’ And she goes, ‘What are you and what do you do?’ Well, I’m a painter and I want to paint. And she was, ‘Then do it.’” He did, and hasn’t looked back.

“Pretty much this man lives and breathes art,” Gia says. “I’m not sure we talk about anything else, really. If he is not painting he is reorganizing his paints by size and color, and his tools by what medium they are used for.”

[HEAR MORE: What's the state of the Las Vegas art scene? Hear a discussion on KNPR's State of Nevada.]

“He didn’t call me or answer the phone for a week!” Gia says. “He was that devoted to finding out how to do it correctly and define his style. I could have killed him over it.”

In other words, you totally invest in yourself, go all-in on the notion that talent is really applied learning. For Henninger, it paid off in new levels of control and photorealism. The response he got to a quartet of Beatles portraits told him he was onto something.

“I knew I had something different,” he says. “It set me apart from everyone else here, and that was really important.”

“James is a savant who articulates an innate mastery of the figure flawlessly,” says gallerist Laura Henkel, whose Sin City Gallery is also in the Arts Factory. And although Michelangelo never painted The Beatles, she makes the comparison anyway, specifically to the master’s unfinished Slaves sculptures: “The forms emerge, breaking free of all conventional restraints, ready to engage the beholder with a captivating presence.”

It paid off professionally, too. The years of non-art jobs are behind him. “I’m doing very well,” he says. “I’m very happy that I’m not working at Burger King.” He keeps his prices affordable, he says, and in the right mood, “If I’m doing a small one, buy me a couple of beers, you know? I don’t care.”

Mostly, he works.

The more Henninger describes himself and his routine, the more he seems like a figure from a Ralph Steadman sketch — manic, obsessed, arms a twisted blur, overfilled skull bursting open. He says he paints an average of two pieces a day, not waiting for the paint to dry on one before embarking on another. “I want to get it done, get it out of my head,” he says. “In 18-20 months, I’ve done over 600 encaustic paintings.” He says he’s sold every one. (Short of subpoenaing his receipts, there’s no way to verify that, of course.)

So you’re not one of those artists who wait for the muse to arrive?

“No,” he says. “They’re pussies. No offense.”

And because self-invention never stops, he taught himself to make eye-catching wire-mesh sculptures that look like crosshatched drawings, and is heavily researching printmaking techniques. There’s always another skill to pick up.

Except color. “Color scares me,” he admits. Shades of gray are controllable; the expressive power of color is a vast and hard-to-harness thing. “When I get enough money that I can take two or three months and really study color, color theory, then yes.”

It’ll happen. This is what he does, this is the life he’s made for himself. “I don’t have anything else to do,” he says. He lives in a one-room apartment that is essentially a studio with a bed, “up to my knees in art supplies.” What’s he gonna do, sit around and watch TV? “I crave this. I have to learn as much as possible — I have to figure it out; if I don’t figure it out, I’m gonna go nuts.”