Dance takes a serious toll on the human body. So why don’t Las Vegas’ most prevalent professional athletes get more help coping with the consequences?

Evening sun seeped through the drawn blinds in a studio at Sherry Goldstein’s Yoga Sanctuary, highlighting the cheeks and shoulders of the dozen students who’d signed up for Rachael Sellars’ anatomy workshop in June 2015. Seated in a circle, they introduced themselves one by one, explaining why they were there.

“I’m a former dancer,” one woman said, “so I have a couple old injuries. I’m interested in learning more about how good alignment can help me deal with my low-back pain.” A person or two later, the line was repeated, “I’m a former dancer,” this time in relation to shoulder surgery. It soon became a joking refrain — “also a dancer,” “danced all my life” — to preface the litany of aches that had brought more than half of those present to yoga in search of relief, and to the workshop that day hoping to reassemble the pieces of their disjointed bodies.

“Well, I danced for 30 years, in addition to teaching exercise classes and doing personal training,” said Michele Chovan-Taylor, a muscular redhead with hazel eyes who was once the gold-painted girl in Splash at the Riviera and dance captain for Legends in Concert at Imperial Palace. “So, I have neck issues — I can’t turn my head more than this (she demonstrated with a stiff glance to the right) — back issues, hip issues and knee issues. Basically, I’m a wreck from head to toe,” she laughed.

Chovan-Taylor, Sellars and the other retired dancers at the yoga studio that day are a representative sample of Las Vegas’ largest professional athlete population, albeit of the artistic variety. According to national labor data, Nevada has the highest percentage of dancers and choreographers per capita in the United States. In the 15-year period from 1990 through 2005, the National Endowment for the Arts reports, the state averaged seven dancers and choreographers per 10,000 people, and Las Vegas was home to more of the professionals than any other metropolitan area, including New York and L.A. Although the numbers have dropped since then, Las Vegas still leads the nation in dancer employment.

As other cities grapple with their professional football players’ head injuries and baseball players’ drug addictions, the costs of high-impact, high-stakes sports are coming to light. Meanwhile, under our noses, legions of (mainly) women struggle unacknowledged to cope with chronic pain caused by years of service to the entertainment capital of the world.

“The showgirl is an icon — the silhouette of her does reference the city still,” says Karan Feder, an entertainment scholar who curates the Nevada State Museum’s collection of showgirl costumes. “We may move past that eventually, now that we’re losing Jubilee! and we won’t have a show like that anymore. … But I’d say for the near future, the showgirl is still going to be a representation of our city.”

"I consider dancers our early settlers, who defined our city and made it what it is today."

And how does the community repay this icon? Inconsistently. Cirque du Soleil’s 81 full-time dancers have comprehensive employee benefits, including access to an in-house performance-medicine department and auxiliary services such as massage and personal training. A few other large productions offer similar services. But outside this utopia, dancers face an uneven landscape of contracts that may or may not include health insurance, paid leave and work rules designed to minimize bodily stress. Locally based shows don’t have the union agreements that are common in Chicago, L.A. and New York and offer members benefits such as pension and limits on physical demands. Professional dance associations have no Las Vegas chapters, and the national organization created to help dancers transition to other careers is currently in flux itself.

According to the 20 current and former professional dancers interviewed for this story, a dozen of whom have worked primarily in shows on the Las Vegas Strip, the industry has made great strides in teaching students to stay healthy through proper nutrition, full-body conditioning and rest. At the same time, they say, the act of dance is getting riskier.

“After 9/11, so many shows closed or went down to one performance,” says Sellars, a tall former Rockette with a mass of black curls pinned back in a loose bunch. “To bring people back in after that, they had to have a shock value — either extreme acrobatics or extremely sexy. When I saw that happening, I was like, ‘Oh my god. I have to do something else with my life.’ But so many of my friends were stuck. The only thing they knew was dance.”

For them, and all the starry-eyed debutantes waiting in the wings, what promise does Las Vegas offer for life off-stage?

Living the dream

X Burlesque, a lounge show at the Flamingo, opens with a jarring throb of Metallica and strobe lights. Five women wearing short, black leather jackets appear inside a huge, empty picture frame on the center of the stage. The one in the middle stands out — taller than the others and the only blond. Known to her friends as Smithy, Stephanie Smith has sharp, classically pretty features and sinewy limbs that will come in handy during the second act, when she will take to the pole for a show of gravity-defying athleticism. But for this introductory number, the goal isn’t technical, it’s functional: to introduce the dancers and the risqué tenor of the show. Within a minute, all five tear away panels of their jackets, going topless. Facing away from the audience, they sway their bare bottoms in sync as the lights and music abruptly go out.

It’s tempting to suppose that the Smithy of 17 years ago — graduating from Toronto’s Ryerson College with a three-year performing arts degree after some 15 years of classical ballet, jazz and tap school — didn’t picture herself here at the age of 39. It’s also wrong. She loves her job.

“I have an awesome deal,” she says in her Desert Companion interview. “I actually am a swing, which is like an understudy who replaces the other girls on call. When I came back after taking a year off in 2012, I didn’t want permanent days. I say yes to almost everything unless I can’t. … But it’s nice to be in charge of your own schedule and to be able to say no.”

Smith’s trajectory illustrates the most recent phase in the evolution of professional dancing on the Las Vegas Strip over the past four decades. Following stints at Tokyo Disneyland and on Holland America Line cruises, the native Canadian came to Las Vegas in 2002 for the launch of Showgirls, a traditional topless revue at the Rio, and its accompanying HBO documentary, Showgirls: Glitz & Angst. After six months on the reality TV-style production, she went on to dance in the Rockettes touring company, Midnight Fantasy (which later became just Fantasy) at the Luxor and, since 2009, X Burlesque. Over the years she’s gone from having a full-time job to her current status as an independent contractor, with one steady part-time gig complemented by temporary assignments at conventions, concerts and special events.

Compare this to the 22-year career of Linda Le Bourveau. The Northern Californian came to Las Vegas on vacation with a boyfriend in 1969, and went looking for work on the Strip after the couple ran out of money. Still leggy and sparkly eyed at 64, Le Bourveau tells how she landed a spot in Lido de Paris at the Stardust and, aside from a two-year stint at the original Lido in Paris (to avoid an unwanted affair with Stardust owner Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal, she says — but that’s another story), performed in the Vegas show continuously until it closed in 1991. The entire time, she was a full-time hotel employee with benefits, including medical insurance and paid vacation. Plum positions like this — relatively more lucrative and stable than the rest of the national dance scene — drew masses of dancers to Las Vegas looking for work.

“When these shows were started, men and women came from all over to dance here, and without these shows, they would have never landed here,” Feder says. “I consider them our early settlers, who defined our city and made it what it is today.”

Chuck Rounds and Minnie Madden, who run Callback News, a 27-year-old trade publication for the Las Vegas entertainment industry, estimate that the showgirl dance business peaked between the late 1970s and the early 1990s with productions in huge casino showrooms that cumulatively employed as many as 600 dancers at a time along the Strip. Today, they put the total number of dance jobs at around 200.

“ Jubilee! once had 120,” recalls Madden, who danced in lounge shows in the ’70s and ’80s and started the newspaper to meet the need for a clearinghouse of audition postings. “Those shows were very popular, because it was just singing and dancing with a theme and fabulous wardrobes.”

February 11, Jubilee!, the last of these iconic shows, closed. Several factors contributed to their demise, according to Rounds and Madden: the corporatization of casinos beginning with Howard Hughes, the implosion of old buildings with huge showrooms, the advent of “four-walling” — casinos renting performance spaces to production companies, which then have to do their own marketing and promotion — and the multi-property deal between Cirque du Soleil and Mirage (now MGM Resorts).

“Nobody would produce Jubilee! in a four-wall, because it’s too expensive,” Rounds says. “Nobody has that kind of money. A lot of those shows were replaced with magic shows and concerts, which have a few dancers, but not dozens.”

Madden adds: “Once production shows went out of the hands of hotel owner-operators and into (the hands of) private production companies, the number of shows started to decline, the genres changed and the business model changed.”

The new paradigm offers dancers few full-time jobs with benefits outside Cirque; most, like Smith, are freelancers. Meanwhile, circus acts, hip-hop and other performance trends have infused dance with gymnastics, such as aerial silk routines or Smith’s pole number. Some dancers end up transitioning completely to acrobatics, where there’s more steady work.

One example of this is Blake Carter, who studied dance at the University of Central Oklahoma and came to Las Vegas in 2009 to audition for Le Rêve after dancing in theme parks, on cruise ships and the L.A. commercial circuit.

“Once I got to Vegas, I switched mainly to circus and acrobatics,” Carter says. “I found a love for that.”

Today, he does a hand-to-hand balancing act with partner Chris Jones. Called Duo Ronin, they’re their own bosses and perform around the country using Vegas as a base of operations. Like Smith, Carter likes being in control of his own schedule. But there’s a major drawback to this lifestyle, they and the others interviewed for this story who haven’t retired yet say: When they’re not working, they’re not getting paid. And when they’re injured, they can’t work.

The show, going on

I broke my ankle on Christmas doing the hypnosis show (Marc Savard Comedy Hypnosis at the V Theatre in Planet Hollywood). It’s the silliest thing, because I wasn’t even running or anything. I just slipped on the stairs. I was coming off stage to change into the next costume, and I slipped down — there were like four stairs — I slipped down the last step and broke my ankle. (Did you finish the show?) Yes. – Jacky Pagone

With a broken ankle, Jacky Pagone finished with Marc Savard Comedy Hypnosis show at Planet Hollywood.

Tiny and dark-featured, Jacky Pagone radiates the self-awareness that dancers get from more fully inhabiting their bodies than other people. She was a ballerina before she was a showgirl, evolving, over 19 years in the profession, from full days of rigorous pointe work, which had given her arthritis in her toes by high school, to what she describes as the relatively low-impact job of assisting magician Nathan Burton and hypnotist Marc Savard at Planet Hollywood.

In the world of dance, the Las Vegas Strip is unique territory. Other big cities may have as many dancers, or more, but a greater percentage of them are often concert performers, such as those in nonprofit ballet and modern dance companies. New York has a large population of these working alongside musical-theater performers on and off Broadway. And Los Angeles has a lot of commercial dancers in film and TV. Although Vegas has all these kinds of dancers too, its specialty is, for lack of a better word, showgirls — dancers who are part of casinos’ resident entertainment, from headliner concerts and magic acts to topless revues and variety shows. (And within the broad “showgirls” category, there are many styles of dance, from adagio to tap.)

“I didn’t want to go to Vegas, because I was living in New York, and it seemed like the entertainers’/dancers’ zoo, from a New York perspective,” says Ivorie Jenkins, a classically trained concert dancer who nonetheless did move here in 2010 to perform in Cirque du Soleil’s Viva Elvis. “I didn’t want to trade in my artistry for being a pawn in someone else’s show. But I knew it was a great opportunity. I knew what Cirque meant in the world of entertainment and dance.”

The Vegas dance ethos pre-dates Cirque, of course. Amber Sorgato, a Boston Conservatory graduate and current owner of Studio 34 dance academy, nails it when she recalls her time in the early 2000s show Storm at Mandalay Bay: “It was definitely my official Vegas show. I had a wig and high heels and booty shorts and push-up bra, and I was like, ‘All right. Let’s do this!’”

The local style may be known as more fantastic and provocative, but it isn’t necessarily easier than others on dancers’ bodies. While concert dancers put in grueling eight-hour days practicing unique combinations of technical movements for shows that typically run for a few weeks, showgirls do the same sequences, once or twice a night, night after night, week after week, for months or even years — often wearing high heels and on precarious staging. (Headdresses, now rare, are another particular local stressor.)

Dancing of any kind, anywhere comes with myriad occupational hazards — set malfunctions, for instance, or one partner dropping another — that are difficult for even the most conscientious company to avoid all the time. But the two seemingly highest risk factors for Las Vegas dancers, repetition and equipment, are within the industry’s control.

Nancy Kadel, a Seattle-based physician who co-chairs the Task Force on Dancer Health backed by nonprofit association Dance/USA, says most dancer injuries are caused by overuse of the body. Locally, “overuse” translates to “repetition.”

“The repetition of the job is how you get hurt,” Chelly Franken, a former dancer in Viva Las Vegas at the Sands, Country Tonite at the Aladdin and Folies Bergere at the Tropicana, says. “You’re always kicking the same leg, doing the same movement, going the same way.”

Performance Health Center’s Katie Hightower, who believes she’s treated dancers from every show on the Strip in the last decade, says the most common injuries she sees in women are in the feet, ankles and knees; men tend to have more shoulder problems, from partnering; and both males and females have neck issues.

Back pain is also prevalent among the dancers interviewed for this story: A few report having herniated discs in their spines, and a few others say they have degenerative arthritis, ranging from the neck to the low back. Almost all say they have chronic back pain of some sort, or acknowledge that if they don’t yet, they probably will someday. Chovan-Taylor, who has degeneration in both cervical and lumbar vertebrae, says that’s the nasty thing about overuse injuries: “They don’t rear their heads until years later.”

“Most of what I see is not an overt injury; it’s cumulative,” Hightower says, “especially on the Strip, where they’re doing 10 shows a week. They may not be doing something that stressful if you do it once, but multiply it by 10, and it becomes very stressful.”

And, she adds, “The shoes they wear are not the best.”

If a dancer’s most vulnerable body parts are her feet, ankles and knees, then her most important piece of protective equipment is her shoes. Technical footwear is designed to support the joints and absorb the impact of landing jumps, but even dance shoes, if they have heels, may increase the risk of injury. Citing a late-1990s study of Broadway theater dancers, who typically wear high-heeled shoes, Kadel says they can expect four to five injuries per 1,000 hours of dance. A showgirl dancing 20 hours a week would hit that number in less than a year.

Le Bourveau remembers having custom-made heels when she danced in Lido de Paris. Cobblers would come to Las Vegas from France, she says, and take detailed measurements of her feet. (After retiring from dance, she transitioned to a related field, today working as a costume technician for Cirque.) Still, Le Bourveau has had four knee surgeries since she retired. Shoes today usually aren’t custom-designed and occasionally aren’t even specially made for dancing. Some — like those worn by the X Burlesque dancers — have four-inch or higher heels. The more physically demanding the role, Kadel says, the greater the risk for injury. So, if you add extreme dance moves, such as knee-drops and standing splits, to high heels, the risk is compounded.

Moving and sloped stages, along with those made of inflexible material, further aggravate this risk. A controlled trial at Long Island University in 2008 found that professional dancers performing on raked stages (those graded upward away from the audience for better visibility of performers) sustain more injuries than dancers who perform on flat stages. More frequently seen than raking in Las Vegas, sources say, is metal — rather than wood or the heavy vinyl surface referred to as “Marley” — which is necessary to support very heavy props, like those used in magic acts.

Angela Albuquerque, who performed with Siegfried & Roy from 1999 to 2003, tells how she and her fellow dancers would measure themselves at the beginning of the week, after a couple days off, and then again at the end of the week, “after jumping around on a steel stage.” They’d be a half-inch shorter at the end of the work week, she says, from repeatedly landing jumps on the unforgiving surface, compacting their spines. She suspects the excruciating sciatic nerve pain she occasionally feels is due to performing not only on steel, but also on moving stages for Princess Cruises.

The local producers who agreed to talk to Desert Companion believe they do their part to keep their dancers safe. Small to mid-size companies Anita Mann, David Saxe and Stabile Productions stage their shows — Fantasy, Planet Hollywood’s 13 shows, and the four X shows ( Burlesque, Country, Men and Rocks), respectively — on flat wood or Marley surfaces. Both David Saxe and Anita Mann, who together employ more than 50 dancers, say they require technical footwear. Mann, whose mile-long resume includes dancing with Elvis at the Hilton and choreographing the Solid Gold Dancers in L.A., says she’s rejected shoes that her Fantasy dancers have asked for because they were unfit for performing. Angela Stabile, co-owner of Stabile Productions, says her company doesn’t have restrictions on shoes, such as heel height, but her dancers work only two and a half hours per night on average.

“I myself was a dancer, and we had incredibly high heels in Crazy Girls,” Stabile says. “With X Burlesque, it’s all very visual. Some numbers are barefoot, and one’s en pointe. It depends what the number calls for, but you get used to it.”

Cirque du Soleil’s spokesperson, Jenelle Jacks, says that its artists’ shoes and stage surfaces vary from show to show, theater to theater, and experts determined what is best in each instance.

In addition to the broad safety requirements that apply to all workplaces, the Occupational Safety & Health Administration has some regulations that address theater particulars, such as mandatory guardrails, safety nets or personal arrest systems for walking surfaces six feet or more above a lower level. Nevada OSHA spokeswoman Teri Williams says employers with 10 or more employees have to establish and implement a written safety program. “This safety program should address the specific hazards related to their particular industry and workplace,” Williams says.

However, independent contractors aren’t counted as “employees.”

The U.S. dance industry doesn’t formally address its endemic risks, such as shoes. Despite attempts to create standards, none that are universally agreed on exist, according to Amy Fitterer, executive director of Dance/USA.

“It’s actually a point of contention,” she says. “On one hand, there would be a desire to see nationally published standards that could be voluntary but are encouraged. But every time we’ve started to go down that path, ironically, choreographers and small-budget companies get very, very concerned, because they may already be struggling to put together rehearsal times for their dancers to get together.”

Mann doesn’t think standards are needed, albeit for a different reason: “I think you have to use your best judgment as a human being. Even if there were standards, as someone who has great respect for dancers, I would go beyond them. As I sit here, looking at my knees, after dancing every day for decades, I know how hard dancers work. Your body gets beaten up.”

The best way to minimize the risk of repetitive stress injuries, Hightower says, is cross-training. Dancers today often incorporate activities such as riding a stationary bike or taking Pilates classes into their workouts to maintain balance and avoid overuse of certain body parts. Although all producers encourage their dancers to warm up and stretch before and after shows, overall fitness is an independent contractor’s own responsibility.

"You learn you better recover very quickly or your spot will be taken, unfortunately."

Kadel says, generally, the more wellness services are available on site, the more the risk of injury is reduced. In dance, this availability ranges proportionate to the size of the production company — from Cirque’s full staff of physicians, physical therapists and personal trainers, to Mann, Saxe and Stabile’s policies of providing such services as needed.

But in order for dancers to take advantage of these services, they have to admit they’re injured, and their failure to do so may be the biggest risk factor of all.

To understand why dancers would keep quiet when they’re hurt, you have to get inside their heads. Those interviewed by Desert Companion say the job defines them: Dancing is in their blood, who they are. Embracing this identity means accepting the risk inherent in the job. All our sources had sustained at least one sprained (or “rolled” or “twisted”) ankle — and most had many more — during their careers, but only a couple listed them among their injuries when first asked. Only after prodding, and then reluctantly, did they acknowledge sprains, even those that required days off work.

Asked to explain this, they give some variation of the answer: Dancers are taught, either implicitly or explicitly and often from a young age, to grit their teeth and perform through pain. A good dancer is one who doesn’t complain.

Sometimes, it’s a matter of job security. “You learn you better recover very quickly or your spot will be taken, unfortunately,” Albuquerque says. “There are so many of us out there, especially females. The guys have it a little easier. The females — there’s somebody ready to take your place. And when you’re an independent contractor, they’ll only wait for you so long.”

In other cases, there’s something more complicated at play. “The die-hard dancer doesn’t want anyone to know they’re injured, and they’re going to go to class and do the show anyway, because it’s embarrassing to them. It’s a fail,” Pagone says. “Everyone works through aches and pains and injuries and breaks. Everybody does it. Everybody pushes through because you love it. When you’re onstage, you kind of forget about it. It’s okay. You go home and you ice. What else are you going to do, you know? When what’s fulfilling is performing? And everything else goes away when you’re doing it?”

Coming together

By the time Rachael Sellars’ stop came up on the New York subway in the spring of 1997, the pain in the back of her right ankle was so bad she needed help standing up and getting off the train. She took a seat on the platform and pulled up the leg of her pants to inspect: From her foot to her calf was a dark, swollen mess. She had told her Rockettes dance captain during lunch break that day that she thought she’d twisted her ankle, so the captain let her take off her heels for the second half of rehearsal. But that only made matters worse. Flat-footed, Sellars had to jump extra high to keep her kicks in line with those of her heeled peers, causing added strain on the ankle. By the time she got to the doctor the next day, he told her, the Achilles tendon was nearly severed. Her dream of dancing at Radio City Music Hall ended on her second day of rehearsal. After a month of physical therapy in New York, Sellars headed to Nevada, where she would eventually land a series of Strip jobs that included Spellbound at Harrah’s, Lasting Impressions at the Luxor, and the Great Radio City Spectacular at the Flamingo. (She also toured with the Rockettes for five seasons.)

More than the pain, several other things about Sellars’ injury experience stick out in her mind, things other former Rockettes also note.

“They treated me so well,” she says. “The show was unionized, so they sent me to the doctor right away. I had full workers comp. Because it happened in New York, I had to do physical therapy there, even though I didn’t live there. I was there for a month before transferring to Reno, where I thought I would audition for a show at Lake Tahoe. But I couldn’t even walk. It took six months of physical therapy to heal, and they covered everything.”

“During Rockettes, you were encouraged, if something happened, to report it,” says Clare Tewalt, who danced in the Christmas show from 2004 through 2008, in addition to performing in Spirit of the Dance at the Golden Nugget, World’s Greatest Magic Show at the Greek Isles and Shag With a Twist at the Plaza. “They’d have someone from the union watching the clock, and after a certain amount of time in our heels, we took them off and practiced in flats.”

“Rockettes were the most empowered female dancers that I worked with,” says Sorgato, whose other shows included Notre Dame at the Paris and Céline Dion’s A New Day at Caesars Palace. “I remember thinking, before I started dancing with them, that they were just up there to look pretty and do a bunch of kicks, but they were very educated and intelligent.”

“That was the most money I made,” Smith says of her two Rockettes tours. “It was $1,250 a week, and that was in 2002.”

Attention to safety, comprehensive benefits, good pay, a say — the very reasons members of a profession organize. Radio City has a contract with the American Guild of Variety Artists, or AGVA, one of the unions that welcome dancers. Others are the Actors’ Equity Association, American Guild of Musical Artists and SAG-AFTRA. A few shows that have come to Las Vegas from cities where they have union contracts bring those agreements with them. Jersey Boys is a current example; past ones include Lion King and Mamma Mia! But dancers have never organized in Las Vegas, and efforts to do so are the unicorn of the local industry: Everyone remembers it happening, but no one can recall where or when, exactly.

If you have no union, you have no real contract. You have no protection at all.

Why no dance unions here? Opinions vary, from the prevalence of corporate show ownership to the relatively good pay and conditions that dancers enjoyed in the industry’s nascence. But almost every dancer agrees that the profession is ripe for union protections today.

“When you dance here, unless maybe you’re doing a Cirque du Soleil or Broadway show, if you have no union, you have no real contract,” Tewalt says. “You have no protection at all. … I guess then it’s down to the benevolence of your employer. Are they going to take care of you? And if you have an injury that’s going to put you out of work for a long time, who pays for that?”

Contracts for Las Vegas dance work come in all shapes and sizes, due to the range of producers’ budgets, from 150-seat, seven-times-weekly shows like X Burlesque to 1,800-seat, 10-times-weekly productions like O. Dancers may be part- or full-time, permanent employees or contractors; they may be temporary or on-call, or work with no formal contract at all. They may be hired by an agency, talent-broker, producer, hotel or entertainment corporation, but in most cases outside the big shows, they’re self-employed, responsible for paying their own taxes.

“Like most dancers, I count from five, six, seven, eight, so I give all my numbers to my tax man,” Pagone jokes.

Contract work is unreliable almost by definition, yet the current dancers Desert Companion interviewed report that their employers accommodate interruptions. While Pagone’s broken ankle healed, she says, Marc Savard performed without an assistant and let her do office work until she could return to the stage. Smith says that when she took time off from Fantasy after her mother’s death, Mann held her position until she got back.

Work schedules for local dancers are also erratic. Shows may run in the afternoon, evening or late night; once or twice a day (occasionally three, with a matinée); five, six or seven nights a week. Call times can be 30 minutes to an hour and a half before curtain, depending on how long it takes to apply makeup and warm up. Rehearsals may be before, between or even after performances, in the wee hours of the morning; they may be every week or as-needed, say to integrate a new cast member or “clean up” a number, in industry parlance.

Albuquerque’s description of her schedule at Siegfried & Roy makes it sound almost like a regular job: 6 p.m. to 1 a.m. five nights a week. Contrast that with a freelancer, who might tend bar 2-7 p.m., perform in a show 8-10, then do a go-go gig 11 p.m.-2 a.m., dancing a half-hour on, half-hour off. And if regular physical training isn’t provided for by her employer — through on-site facilities, lessons and instructors, as Sorgato enjoyed during her time with Céline Dion — then she has to go to the gym or take dance classes on her own to stay fit.

“Now most casinos have a multiplex mentality, so instead of running one big show three times a day, they run three different shows,” says Chuck Rounds of Callback News. “So every dancer has at least one other job.”

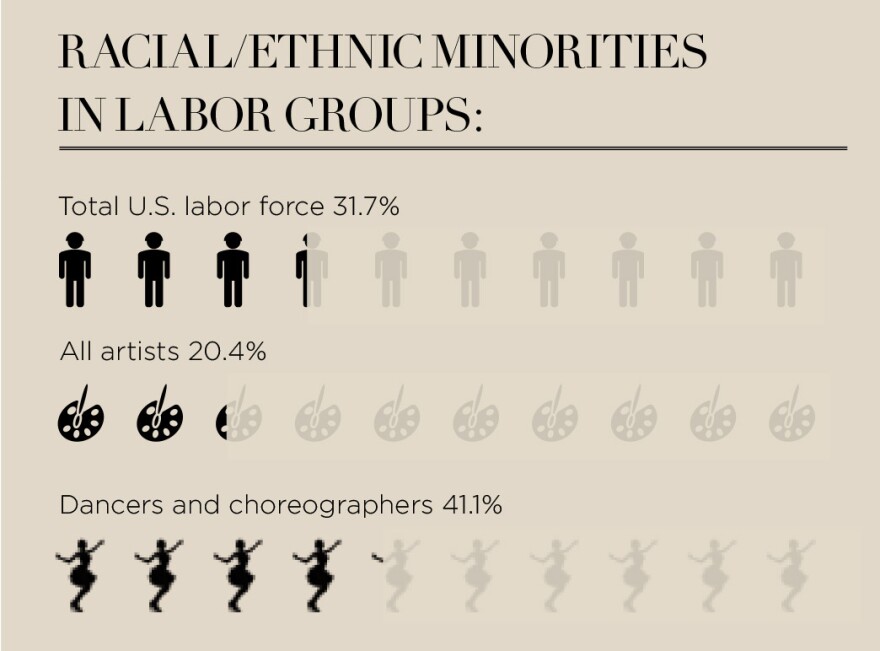

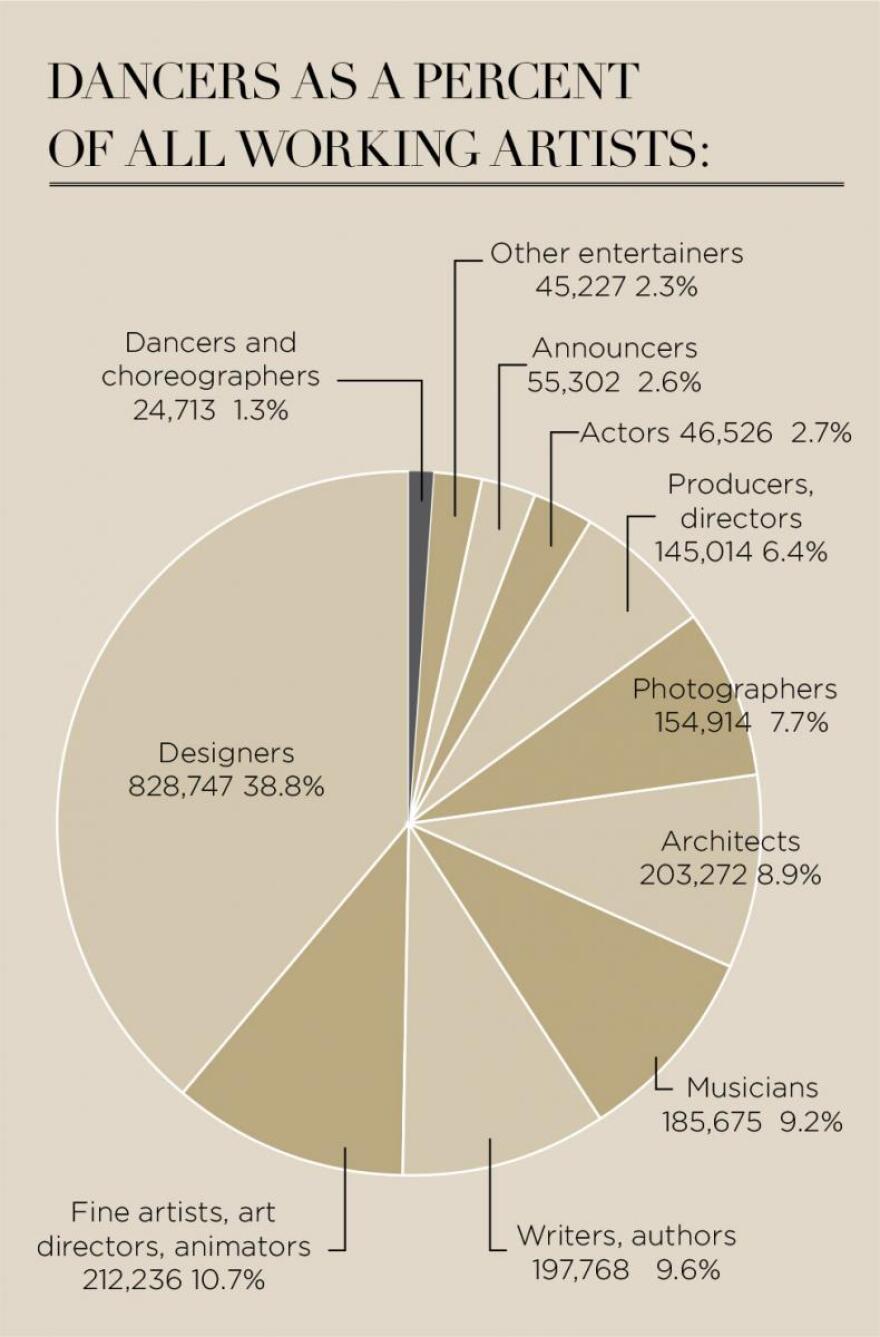

Because of this, it’s almost impossible to pinpoint dancer pay. Sources report having made as little as $633 a week for 10 shows at Jubilee! and as much as a couple thousand dollars for one freelance performance of a specialty act. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ data isn’t necessarily helpful, because it’s employer-reported and doesn’t include independent contractors. According to the bureau’s May 2014 employment and wage estimates, dancers make an average of $19 per hour, compared with the national average for all occupations of $23 per hour. (Remarkably, Nevada, which has 1,030 dancers per capita, the most after Hawaii, also pays the best, at $32 per hour.) And dancers make less than all other artists except photographers, according to a 2010 report on arts occupations by the National Endowment for the Arts; coincidentally, dance has the highest percentage of females and minorities.

Sources don’t point to discrimination when asked why they’re underpaid, though. They turn, again, to dancer psychology.

Sorgato says: “Dancers are used to being vocally quiet, because we express ourselves through our bodies. Look at management meetings. The dancers would be all plopped on the floor in groups, like little kids in kindergarten. You’re just so used to being on the ground stretching. You could speak up for yourself no matter where you’re sitting, I guess, but in the corporate world, in any other job, a 32-year-old woman is not going to be sitting on the floor while a manger stands up and talks down to her, physically.”

Even more telling, every dancer interviewed for this story said she would do or have done it for free.

“You don’t become a dancer to get rich,” producer Anita Mann says. “You become a dancer because you are a dancer. You have to dance. There is no finer fulfillment for you. Yes, we have to pay our bills and raise our kids. But we’ll do anything to dance.”

Low pay is fine if the benefits are great — particularly for a physically risky occupation. But here, too, offerings vary widely. Stabile’s dancers are independent contractors, responsible for their own health insurance (though if they are injured on the job, they qualify for workers comp); Saxe’s company plan covers individuals who work 30 hours a week or more; and Mann gives her dancers medical, dental and vision insurance. Only Mann offers paid leave beyond what’s covered by workers comp.

When Ivorie Jenkins herniated a spinal disc, putting her in a back brace for two months and benching her from Viva Elvis for three, she says, Cirque du Soleil paid her 75 percent of her salary, covered all her medical bills and provided for daily physical therapy, as well as acupuncture, chiropractor and other treatments. Large employers often have extra, non-medical perks as well, from yoga and nutrition classes to career and psychological counseling.

“The level of care depends on (the company’s) resources,” Jenkins says. “I think they all want to give the best they can. … When you join a company, you know how prestigious it is.”

Smaller producers agree that taking care of an employee’s on-the-job injury is in everyone’s best interest. But the contractor paradigm can pose problems for those who do offer benefits.

“In the old days, a dancer danced in a show and that was it,” Saxe says. “But now, they’re working so many different types of gigs and running around like crazy. So, sometimes, we’ve had someone with a hurt knee who didn’t hurt it at our show, but then they didn’t have insurance on the other gig, so they’ll put in a workers comp claim with us, and it’s a little frustrating.”

For the contractors, it’s not ideal either. Besides the financial burden, they say, supplying their own care means the providers they have access to may not understand their needs.

“If you do some average physical therapy, it’s not getting you ready to go back and do what we do,” Blake Carter says. “You can lift your leg 90 degrees? They’re like, ‘Oh, you’re doing great!’ So — I won’t name names — but I had (a physical therapist) from another show come help me on their own time outside the show, which they’re technically not allowed to do. But I had to take care of it on my own.”

Perhaps due to the lack of formal support systems outside large companies, Las Vegas dancers have forged their own network of self-care, sharing contacts, knowledge and skills. Outsiders see the city as having a remarkably cohesive dance community, and many of those within it agree.

“It’s not about what’s going on onstage,” Franken says. “Backstage you bond so much. You’re naked in front of your friends. And we joke about what just happened. ‘I couldn’t find my glove, but the audience will never know I had a black sock on my hand!’”

“I get very nostalgic now when I watch behind-the-scenes shows about auditions,” Sellars adds. “It’s the best thing ever. It’s a family vibe. You’re going through something together, and you have each other’s back. My experience was camaraderie of dancers — women — working together and being creative. … The injuries didn’t matter. I never got sick of going to work. I loved it. And I miss it.”

Moving on

At 33, former Jubilee! blue bell Anaïsa Bates is starting to feel the impact of dance on her body. But she's not ready to quit yet.

Anaïsa Bates, who goes by Nessa, pops a potato chip into her mouth at the picnic table outside The Beat Coffeehouse. “Well, I mean,” she draws out the “ea” and raises her eyebrows, making her huge brown eyes look even huger, “it’s funny. I am considering going back to school now, but it would be for makeup, cosmetology. My mom always did it, and it was something I thought I’d do if I ever stopped dancing. … Now, I’m really getting into it. It just organically happened. But if anything, I’m still trying to get into another show again.”

In 2001 Bates graduated from Las Vegas Academy, where she majored in dance, and went straight to work, first, briefly, as a go-go dancer, and then in Show in the Sky at the Rio and Jubilee! at Bally’s. After three years as a blue bell (the covered dancers) in the traditional showgirl production, Bates decided she wanted to go back out on her own. In 2008, she returned to go-go dancing, combining it with convention work and bartending, which provided her with corporate employee benefits. While she was with Jubilee!, she began dancing with Lost Vegas, a crew made up of other show performers who wanted to create their own art on the side. They’d get paid to perform occasionally, and Bates would practice with them in the early-morning hours after work. She has also danced in the nonprofit group Culture Shock since 2008. In other words, Bates is one of those who’s been juggling multiple gigs for more than a decade now.

But at 33, the nonstop activity is catching up to her. Her knees, hips and lower back hurt off and on, undoubtedly due in part to her innately uneven pelvis and related scoliosis. (Running up and down a couple flights of stairs in heels several times a night for three years to change costumes between Jubilee! numbers probably didn’t help either, she guesses.) She’s on the fence about what to do next.

And she’s not alone. About half of those who shared their stories with Desert Companion had an associate’s or bachelor’s degree — mostly in dance, but also in business, communications and public relations. One had an MBA. Those who’ve moved on most frequently went into the fitness business, teaching Pilates, yoga, Zumba or dance. One became a real-estate agent; another is a medical language specialist. According to federal labor data, full-time fitness trainers and aerobic instructors make $39,410 per year on average.

“Now that I’m older, I wish I’d gotten a degree,” Sellars says. “I wish I had a higher-paying job. I feel like I’m still living the struggling artist reality.”

Yet neither she nor any other source regrets her first career choice.

“If I had a 15-year-old girl in front of me right now, and she was considering going into dance like I did, I would tell her to go for it,” Bates says. “You love it? You work hard. You’ll want to fight through all the times when you’re down on yourself because you didn’t get the job. You eat, sleep and breathe it, and it will happen. Maybe not the way you want it to, but it will.”

The irony is that this career, which elicits such complete dedication, is short-lived. Vegas dancers do seem to keep working longer than their ballet, film and TV counterparts, where, experts say, their shelf life ends in the late 20s, early 30s. “A lot of Cirque du Soleil performers are married with kids and in their 30s and 40s,” says Kristina Blunt, who once danced with Alvin Ailey and on Broadway in New York, and now runs the Vegas Gone Yoga! Festival.

Still, 40 is a long way from retirement age. And most of those interviewed for this story say they didn’t go into dance with a backup plan for life after dance. Recognizing this, Edward Weston created the nonprofit Career Transition for Dancers in 1985. The Actors Fund in New York administered it originally with the support of the unions that include dancers, and it was later spun off as a separate nonprofit. Essentially a grant-giving operation, Career Transition for Dancers funds education and training and provides counseling to help dancers prepare for their second life. Cirque offers similar programs for retraining and in-house advancement.

From 1997 until the end of last year, Joanne Divito was the West Coast coordinator of Career Transition for Dancers. In 2004, Divito brought a national outreach project to Las Vegas. “We decided we wanted everybody in Vegas to know about us, so we went from show to show to tell Vegas dancers about what we were doing,” she says.

“It’s an incredible organization,” Blunt says. “They’ve helped so many people.” She and other sources have used Career Transition grants for training and certification in all sorts of fields, from massage to real estate.

At the beginning of this year, Career Transition for Dancers, as a separate entity, ended. Divito’s position was eliminated, and the grant program was absorbed by the Actors Fund. It has a new West Coast program career counselor, Sophia Kozak, who stresses that scholarships and advice are still available to Las Vegas dancers.

“I’ve been speaking with a lot of dancers from there,” says Kozak, who’s based in L.A. “It’s important for them to know that there’s support available. Injured dancers can get services for what they’re going through.”

But Divito is concerned about the lack of direct outreach. She worries that dancers, who are already overworked and reluctant to speak up for themselves, will be less likely to get help if it means traveling to L.A. for a mandatory orientation. Still, she sees an opportunity for the dance community to leverage its cooperative spirit, band together and create something helpful for future generations.

“When I heard about my office closing,” Divito says, “I said, ‘Yet again, it’s the dancer who gets screwed.’ … I encourage them to start another real organization for dancers. It’s important that these kids have a place to go.”

Anatomy of a dancer

Desert Companion interviewed 20 current and former dancers for this story, focusing on the 13 who have spent a significant part of their careers in Las Vegas. Together, they've put in 120 years here, mainly working in Strip shows, but also freelancing as bevertainers, go-go dancers, convention spokesmodels and in other gigs. Ranging in age from 30 to 64 today, they've performed in everything from Folies Bergère and Siegfried & Roy to Marc Savard Comedy Hypnosis and X Burlesque. This is a composite sketch of the toll it's taken on their collective body.

Working hard for the money

Like any professional artists, dancers are hard to quantify, says Mina Matlon, director of research and information services for non-profit industry association Dance/USA. They may work in non-arts jobs between or in addition ot dancing they may be on-call, independent contractors or constultants. Nevertheless, good estimates exist. They indicate that dance, the arts job comprising the highest percentage of minorities, is also among the worst-paying.

*Source: National Endowment for the Arts, "Artists and Arts Workers in the U.S." (based on 2005-2009 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce)

Showgirls not allowed

Despite its preponderance of professional dancers, Las Vegas is bereft of organizations to represent them. While some dancers report having union cards from productions based in other cities, none had obtained membership through a dance gig here. As for professional associations, Dance/USA Executive Director Amy Fitterer says, “A lot of other major cities have a non-union 501(c)3 whose purpose is to support the for-profit dance community, but I cannot find one in the state of Nevada.”

UnionsActors Equity

Encompasses theatrical productions that include dancers, such as Jersey Boys and Phantom of the Opera, but is mainly for actors, national communications director Maria Somma says.

American Guild of Musical Artists

Focuses on ballet and opera companies, and has no companies organized in Nevada, according to national dance executive Nora Heiber. “The showgirl-type dance scene would be our jurisdiction, but we haven’t been approached,” she says.

American Guild of Variety Artists, AGVA

Contracts with organizations like Radio City Music Hall and Universal Studios — seemingly a fit for Las Vegas-style shows. “The last AGVA show in Las Vegas was the Rockettes at the Flamingo,” West Coast Representative Steve Rosen says.

Professional associationsAmerican Dance Guild

Focuses on New York, and on concert, rather than theatrical,

performers.

Dance/USA

Advocates on behalf of on nonprofit dance companies.

Nevada Ballet Theatre and Sierra Nevada Ballet are members.

National Association of Dance and Affiliated Arts

Has chapters in Connecticut, New York and Wisconsin; none in the West.

Dance Resource Center

Southern California network that welcomes commercial dancers and helped the national Task Force on Dancer Health coordinate screenings in Los Angeles. There is nothing similar for Las Vegas.

National Dance Council of America

Based in Provo, Utah, focuses on competitive dance.

The weighting game

Showgirls aren’t immune to the eating disorders that plague other dance sectors and were brought to the fore by books like Dancing on My Grave, the 1987 autobiography of New York City Ballet principal Gelsey Kirkland. A 2014 meta-analysis of prior research concluded that dancers of all kinds are three times more likely to suffer from eating disorders than the general population.

Among those interviewed by Desert Companion, three talked openly about their struggles with anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia, about half said they’d confronted body dysmorphic disorder at some point in their career, and almost all said that eating disorders were rampant in the companies where they worked.

“Most of us feel like we could always lose five pounds,” says Ivorie Jenkins, a former Viva Elvis dancer who learned to cope with her disordered eating through yoga and meditation.

At 57, Michele Chovan-Taylor hasn’t danced professionally in decades and now heads the group fitness program at Lifetime Athletic. But she’s still haunted by memories of being passed over for roles in her 20s and 30s because of her strong, compact build. “There are still times when I fight the urge to stick my fingers down my throat,” she says.

Some sources associate the lasting trauma with weigh-ins, the practice of forcing dancers to step on the scale weekly, monthly, quarterly — even before receiving paychecks, as they recall. Others say they only had to weigh in if a supervisor thought they looked fat. All see it as part and parcel of the job.

“When you’re going out on stage in a G-string and bra every night, you didn’t want to look overweight anyway,” says Chelly Franken, who once danced in Folies Berg è re.

Editor’s note: The author taught at Yoga Sanctuary from 2006 to 2013, and knows Angela Albuquerque, Kristina Blunt and Rachael Sellars from her time there.