Tight spaces, terrifying falls, broken bones — and ultimate triumph. Hold on tight as you read this digest of outdoor adventures gone sideways, told by those who lived it

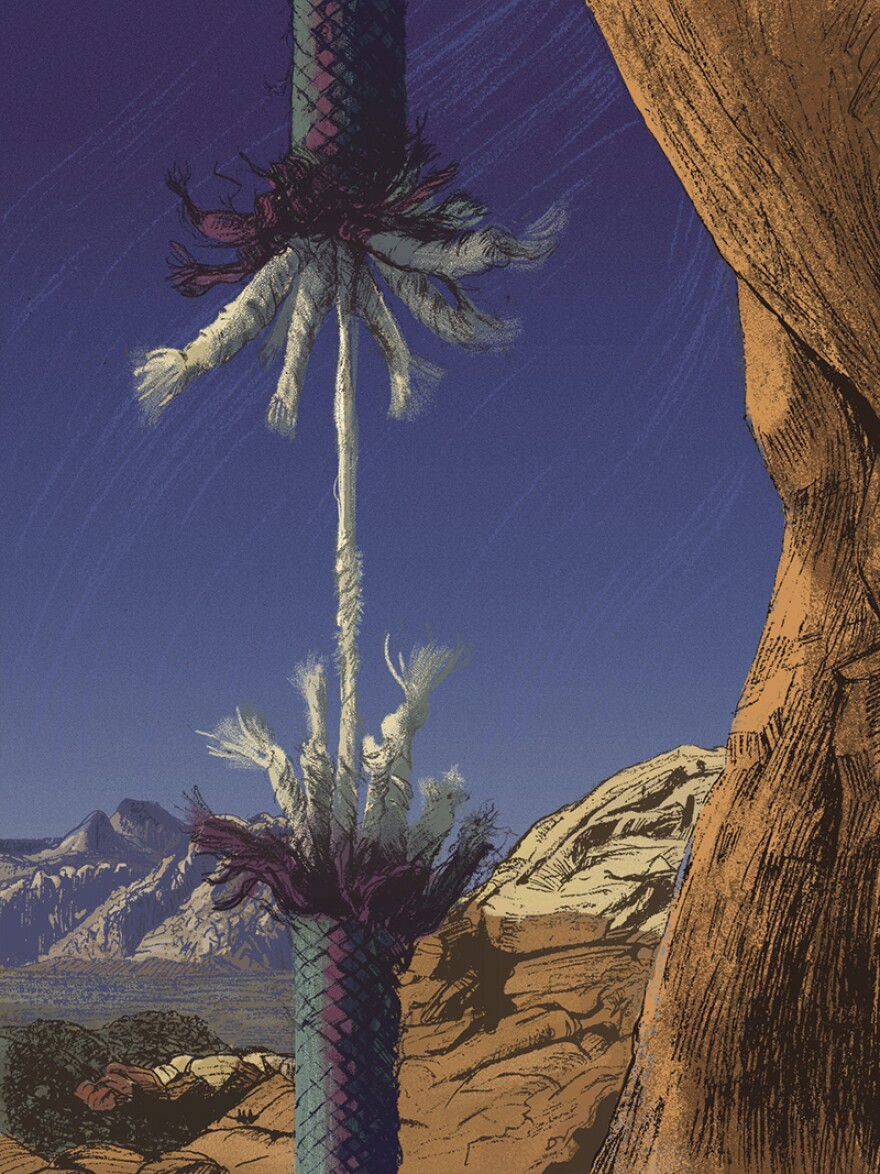

‘I was in over my head’

September 2012

While exploring a canyon in nowhere Nevada, a friend and I got to the top of a cliff where the bottom could not be seen. After more than an hour of trying to figure out how long of a drop we had to deal with, we determined that the cliff had to be at least 400 feet high. We only had a total of 500 feet of rope. You would think, no problem, but this is just the cliff we’re talking about; we needed some rope to continue down the rest of the canyon.

We rigged a system that sacrificed the 300-foot rope but salvaged a 200-foot rope that could be retrieved from the bottom. The only trick was that the person rappelling would have to transfer from one rope to the other.

I was the first person down. In the process of transitioning from rope to rope, a cord jammed in my rappel device. Without thinking, I grabbed a couple loops of rope with my left hand to be able to use my right (brake) hand to remove the cord from the device. Upon removing the cord, the rope, with all of my body weight, cinched down hard around my left wrist.

Dangling freely a hundred feet from terra firma, I was stuck.

I struggled to figure out a way to get out of the jam. After 20 long minutes, I came to the conclusion that the only way I was going to get down was to “snake” the rope around my constricted wrist. I pulled up a few feet of rope with my right hand and fished it through. At first, the pain was minimal. But what I didn’t know is that I was effectively cutting and cauterizing my wrist as I was lowering myself. I finally got down, unable to stand up because my legs were numb. At this point, my bloody, rope-slashed hand had swollen to twice its size.

My friend made it down and, after some time, we continued down the canyon where we handled another 40-foot drop without issue. After a four-mile, cross-country hike, we got to my truck and drove the four hours to Las Vegas. Shortly after getting home, I went to the hospital where I spent two nights and three days.

Moral of the story is that I was in over my head. I had taken about a year off from canyoneering and my skills were not up to par to be exploring new canyons where more advanced skills are necessary. If I’ve learned anything, it’s to make sure I’m well-practiced before taking on such challenges. Jose Witt

‘I think I really hurt my leg’

November 2015

On a typical fall day late last year, I went mountain biking out of Blue Diamond, eager to get in a quick hour before the sun went down. About halfway into my usual loop, I came across another mountain biker sitting up, with his legs splayed across the trail, his helmet a little askew and sweat beaded on his brow. From the panicked look on his blanched face and his trembling hands, it didn’t take much to see that he was injured. Slowing to a stop, I started asking him questions to determine whether he’d need a slow walk or a helicopter ride to civilization.

Oblivious to my questions, he simply sputtered, “Ugh ... I think I really hurt my leg.”

Following his gaze down to his right shin, I could see we’d need the helicopter.

His leg, as dusty and mud-splattered as it was, announced its injury by way of a massive lump protruding from the shin — it was his broken bone just short of puncturing the skin. I asked if he’d called for help. He feebly held up his phone and told me that he wasn’t getting reception.

I had better luck climbing up a bit higher out of the small gorge we were in, and called for a rescue squad.

Flying in by helicopter and “landing” with only one strut on a rock, the other hovering in the air, the rescue team was the picture of professionalism in the middle of nowhere. One of the medics helped the mountain biker get stable while he worked out next moves with the helicopter circling above us.

He asked the guy how he had hurt himself so badly. A bit calmed, the biker explained that he’d ridden to the top of a rock above us, and had gotten off his pedals to stand there and take in the view. He lost his balance and toppled over, the bike coming down on his leg. The medic’s sense of humor delivered some much-needed levity: “So, technically speaking, you didn’t have a biking accident. This is a hiking injury.” Robin Bernhard

‘Guys, I’m starting to freak out’

November 2015

I took a trip with caving club Southern Nevada Grotto to explore Wounded Knee Cave, a wild cave at Red Rock that has been protected under lock and key. It was an encounter with claustrophobia — culminating in a moment of pure panic — I’ll never forget.

I had crawled on my belly through a tunnel to access the cave. Next, I waited in line to shimmy 15 feet up a “chimney” that was so narrow, the guide had advised, “If you fall, just make yourself big. You won’t go anywhere.”

As I scooted my way up this crack, I fit so tightly that I could not move my hand from its position at my waist up to my shoulder. My feet clawed and skidded against the slick limestone, desperate for purchase, and as I looked up for my next handhold, I was greeted with an inky abyss which I knew (because they had gone to great pains to tell me) would transition into a belly crawl that would make this chimney feel downright spacious. And then, the person climbing ahead of me stopped, and I was instructed to wait ... in that awkward spot ... with my hot, panting breath blowing back in my face off the wall in front of me that seemed impossibly close to the wall behind me.

I had been warned about the first climb that it would be a tight, uncomfortable squeeze, and that claustrophobia could become an issue. But I’m a good climber, and I’d done some caving before. “I’ll be OK,” I had told them.

“You’ll be OK,” I now told myself.

I started to panic. The exit of Wounded Knee Cave was only 50 feet away. If I retreated, I could be out in minutes. I’ll give myself 30 more seconds, I thought, as my heart began racing. And then, meekly, I squeaked, “Guys, I’m starting to freak out.”

The trip leaders sprang into action. “No problem. Put your hand here. Now scoot over here. Good job.” And a minute later I was up, catching my breath before beginning the next stage of the trip that taught me caving is not for me. Alan Gegax

‘My feet slipped and I began to drop’

February 2013

I was scrambling at Burlap Buttress, a peak in Red Rock, with three companions who were spotting my ascent of a particularly steep, tricky rock. One companion was on top of the high rock I was tackling, and the two others were behind me in case I lost my grip.

My spotter atop the rock was on his belly, tightly grasping my hand as I tried to shimmy up the sandy, slippery rock. Then, my feet slipped. I began to drop, and next thing I know my hand slid from my spotter’s grip.

My first thought: $#@!! I knew I was in trouble.

The spotters behind me didn’t have time to react — in fact, one was busy taking a photo at the precise moment I fell. I plunged 10 feet down to the ground and, by pure luck, missed the boulders we had climbed up and instead landed just behind them on a rocky patch of sand.

I was lucky to get away with a golf ball on my elbow and a little bruising to my ego — which is preferable to splitting my head open on a rock. Best of all, I was able to continue the hike and reach that beautiful peak. Penny Sinisi

‘A white-hot sheet of sheer, abject terror’

June 2010

Standing at the terminus of Ice Box Canyon with sheer, towering walls to the right and straight ahead, I watched my nephew Nick begin climbing up the rock to the left. Though the grade was not exactly inviting, it didn’t look too forbidding, either. He was only 10, but was a precocious and very aware climber — as he’d shown the last few hours, scrambling over boulders and fallen tree trunks. I followed, noting with concern that the sandstone of the wash had given way to limestone — much slicker and with far fewer footholds. We climbed deliberately, aiming for a prominent ledge high up in the rock. Sweating lightly, we gained it and took in the view. The big rainwater basin at the base looked tiny, and I felt a certain unease creeping up on me. 100 feet up? 110?

As I wondered, I found a small, flat rock and snapped off a throw out into empty space. Watching the rock sail out, then turn on its edge and plummet, my unease morphed into something deeper.

We began the descent a few minutes later, working our way down a crack running diagonally across the rock face, with me in the lead and Nick right behind. The crack became shallower, became a seam, and then barely a wrinkle. My fear became more palpable, and I instructed my nephew to stay close and follow my route exactly: The footing was poor, the grade was illogically far steeper going down, and there was nothing to hold onto.

Sweating hard now, I noted a small but secure-looking ledge below me. I finally got my feet onto it, noting we were still 30-35 vertical feet from safety. Standing and facing in towards the rock, I heard Nick shout — and I realized he’d lost traction. Still on his feet, he slid down the rock on a path that would miss the ledge, about 2.5 feet to my right. I knew he couldn’t stay upright — that his momentum (and the weight of his head and torso) would almost certainly pitch him forward into the rocks below.

Leaning into the rock, I swung my right arm out, fingers formed into a claw. He was wearing a loose, white T-shirt and as my hand found its front, I closed it into a fist. It was at that moment that time itself ... skipped, and in that fraction of a second, I was consumed by a white-hot sheet of sheer, abject terror. It was probably only a fifth of a second, but it was the worst, most sickeningly terrifying moment of my life.

When I regained awareness, I found myself with a fistful of his shirt, pivoting to swing him around onto the ledge.

Badly shaken, we hunkered down, and when a small group of hikers appeared below us, we implored them to call Search and Rescue. It was nearly midnight before we heard the clatter of the helicopter — a sound I never thought I’d find so sweet. Andrew Lanfear

‘Screaming, I run across the desert floor’

May 2005

I do this thing called geocaching, a high-tech treasure hunt. On one such excursion, my search takes me to the end of Horizon Ridge Parkway and leads me on a mile-long hike across the desert. My GPS says I have 30 feet to go. So up the hill I scramble, looking for the geocache.

Suddenly, the GPS goes dead. The only thing in my pack is leftover pizza, water, and a camera. No matter, I think. I’ve come this far. I’ll scramble up 30 feet more and find that treasure. While I’m clawing my way up the scree, fishing in holes, lifting rocks and generally annoying the desert life, the sun sneaks silently behind the horizon.

No matter. I took a desert survival course. Before I left my car, I’d looked up and seen antennas straight ahead. So, I conclude, my car is 180 degrees behind them. But now when I look around, I see antennas in every direction.

I start walking to where I think I left my car. An hour later, I’m jabbering to myself, and two hours later, I’m seeing other people and trains crossing my path. Luckily, there is still a sane part of my brain that tells these hallucinations to go away.

Finally, I get to some kind of an industrial plant. All I know is that there are lights and trucks. But they’re leaving — and it’s now midnight.

So, flashing my camera and screaming, I run across the desert floor, hoping that I’ll arrive before the last truck leaves.

Luckily, I catch it. It’s the best treasure ever. Debbie Prince