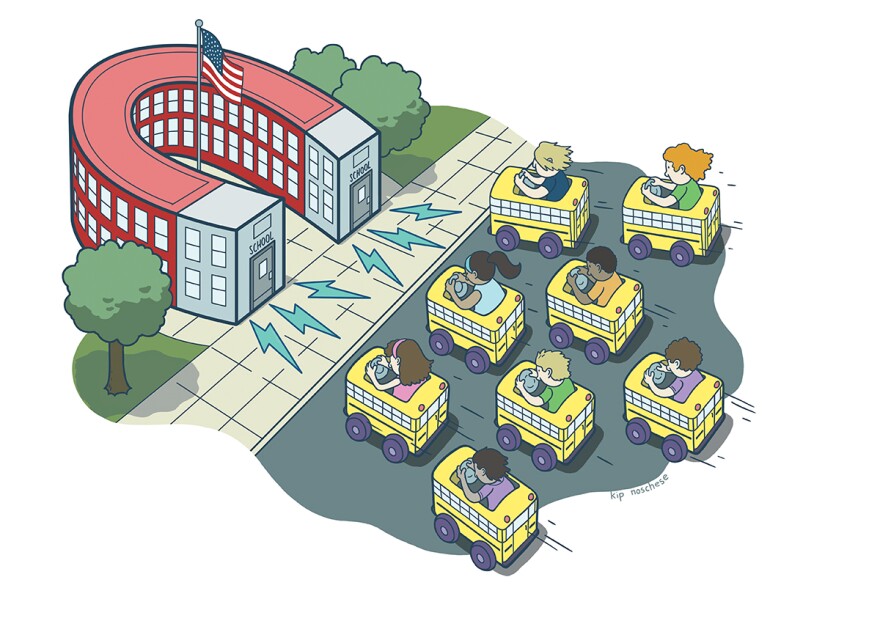

Parents clamored for more magnet programs. The school district answered — but not everyone is happy with the changes

At 7 a.m. on a Friday, a semi rumbles east down St. Louis Avenue near downtown Las Vegas. Painted in blue on the side of the white trailer: “Magnet schools: It’s your choice in education.” Under the tagline is Clark County School District’s logo.

Choice. The concept is more complicated than it seems, especially in this case. Many local parents and public-school students would, indeed, prefer magnets. In the 2014-’15 school year, they submitted 16,600 applications for a third as many available magnet school seats. It’s easy to see why. Clark County’s magnet school program is a bright spot in Nevada’s dim educational picture. While the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s 2014 Kids Count profile ranked the state 50th in the U.S. for education, CCSD bagged 17 awards in last year’s national Magnet Schools of America recognition program. Late last fall, the district announced it would increase the number of available magnet program seats from approximately 5,700 at 25 schools to 9,000 at 36 schools through 2016-’17, effectively giving more parents and students the chance to snag one.

But choice also suggests freedom, or a basic right. That’s how parent Melissa McGill sees it. She believes that, as part of the public education system, magnet schools should be open to any student who meets their rigorous standards. But that won’t exactly be the case this fall in CCSD, and not just because demand exceeds supply. To draw kids (and help alleviate school overcrowding), the new magnet programs were placed in under-occupied schools. Unable to afford to bus every student from anywhere in the valley to whichever magnet school she attends, the district created transportation zones according to programs of study. Busing to magnets will only be provided within each school’s zone. Outside the zone? The student will have to get a ride from mom or dad — or somebody. No ride? They’ll have to attend the magnet school in their transportation zone.

“It’s not actually equitable,” McGill says. “There’s no difference between forcing kids to go to a nearby magnet school and forcing them to go to their zone school.”

She and other parents of kids currently attending magnet schools feel the district is looking to fix something that isn’t broken. Rather than tinkering with a well-run program, they wonder, why doesn’t the district simply elevate the quality of instruction across the board? This, in part, is what the district says it’s trying to do. Extending tried-and-true magnet curricula to 11 more schools will not only fill some unmet demand, but also raise the tide that’s floating all CCSD boats.

“If we could give everyone a seat, we would,” says Gia Moore, CCSD’s director of magnets and CTAs, “but logistically, it’s just not possible.”

Instead, they’re betting that their magnet success can be repeated in new locations — that some years hence, a spot at Del Sol’s fledgling performing arts program will be as coveted as one is now at the prestigious Las Vegas Academy.

Fact from fictionThe magnet program expansion really got the rumor mill churning, and the school district may be partly to blame. The change was one of several rezoning solutions proposed to help solve the problem of under-occupied schools in a generally overcrowded district, says Caryne Shea, who’s been following the issue for parent advocacy organization HOPE for Nevada. The district was eager to present these solutions in advance of school construction bond legislation proposed for the 2015 session in Carson City. So, it rolled out the magnet school expansion with fanfare last fall. And at first, everyone was excited.

“The magnet program is what our district seems to do best, so it seemed smart to expand it and use those under-populated schools to do it,” Shea says. “Most magnets were in the center of the city, so there was a lot of demand for them in the outlying areas of the city, and they picked locations like that.”

Then, the details began to leak out. Some parents interpreted the transportation zones to mean they’d no longer be eligible for the magnet schools their kids were already attending. People showed up in droves at public meetings, angry and confused. HOPE met with Moore and her colleagues in the magnet-CTA program several times. They succeeded in getting a few tweaks made to the plan.

What’s actually happening is best understood in terms of study programs. Take LVA, a performing arts high school, for example. Its middle and elementary school equivalents, called “feeder schools,” are K.O. Knudson and Gilbert. Magnet seats are distributed through a lottery system, weighted to favor kids who are already zoned for the schools with the magnet programs they’re applying for, who have siblings in the program and who come from feeder schools. Starting in 2015-’16, Del Sol High School will have a performing arts magnet program modeled on LVA’s. For the performance arts program’s busing, the city is bisected east to west along Spring Mountain Road. Kids who live north of the line can catch a bus to LVA; those on the south will be provided transportation to Del Sol.

(Transportation zone maps are at magnet.ccsd.net.)

A compromise HOPE engineered with the district grandfathered in students currently attending magnet programs to the old system; they’ll get busing until they graduate. Their entering siblings will also get busing for the time being, and the district extended its magnet school “hubs,” drop-off points where kids can catch buses. Students can still apply for magnets outside their transportation zone, but they have to find a ride themselves.

It’s cold comfort, Melissa McGill points out, for that eighth grade dancer who has his heart set on LVA, but lives outside its transportation zone, has no sibling there and can’t get a ride.

“You can’t just slap ‘magnet school’ on the letterhead and make it a magnet program,” she says.

Moore says the district is doing much more than that. New magnet programs will be funded through the same grants as their old counterparts, and use the same entrance criteria and curricula. Veteran magnet administrators and teachers have mentored the new talent. This summer, new magnet staff will undergo specialized training tailored to their subject areas.

“Opening 11 new programs is fantastic,” Moore says, “but we’ve also worked diligently over the past year to make sure they’re getting the right tools and training to make them comparable to what we already had.”

Then there’s the risk of brain-drain — teachers leaving inner-city magnets for the new programs in the suburbs. A couple of Valley High School’s International Baccalaureate teachers have announced on Facebook that they’re leaving for the new IB at Basic next year. But that may just reflect how CCSD’s teaching talent follows its most motivated students.

“I think overall, the magnet expansion is going to be a great thing,” Shea says. “It provides more school choice and keeps kids more engaged. The transportation thing is unfortunate, and we need more funding for our children anyway, since it is low, compared to the rest of the country … But I have to say, this will work for the majority of parents and students.”