In this issue: Our Restaurant Recession | Integrated Healthcare | The Obsession of The Ringmaster | Introversion Goes Extreme

WE SEEMED INVINCIBLE once, didn’t we? Thirty years of ever-expanding prosperity will do that to you. With Vegas surviving Gulf wars, dot-com busts, recessions, mass shootings and depressions, it felt like the public’s appetite for all things Las Vegas was insatiable. Since 1994, we witnessed one restaurant boom after another: celebrity chefs, the French Revolution of the early aughts, Chinatown's 20-year expansion, Downtown's resurgence — and all of it gave us rabid restaurant revelers a false sense of security. A cocky confidence that the crowds would flock and the champagne would always flow.

Then we were floored by a COVID left hook no one saw coming. In an instant, literally, 30 years of progress hit the mat. To keep the metaphor going, we’ve now lifted ourselves to the ropes for a standing eight count. The question remains whether we can recover and still go the distance, or take one more punch and suffer a brutal TKO.

click for more

There was an eeriness to everything in those early months, as if a relative had died, or we were living in a bad dream. A sense of loss and apology filled the air. Our first instinct was to reassure ourselves. Restaurants were there to feed and help us back to our feet, and the feelings were mutual. Reassurances and gratitude were the watchwords whenever you picked up a pizza or grabbed take-out from a chef struggling to make sense of it all.

Then the mood turned surly and defensive. The moment restaurants were given the go-ahead to start seating people again, the battle lines were drawn. It took some weeks to build the trenches, but by July, what began as a “we're all in this together” fight for survival devolved into a multi-front war pitting survivalists on all sides against each other. Mutual support evaporated as tensions arose between those needing to make a living and those who saw epidemic death around every corner. Caught in the middle were the patrons: people who just wanted to go out and take advantage of our incredible restaurant scene. Suddenly, everyone felt uncomfortable, and in a matter of a few calamitous weeks, dining out in America went from “we're here to enjoy ourselves” to “let’s all struggle to get through this” — not exactly a recipe for a good time, which is, after all, the whole point of eating out.

Reduced hours and crowds meant shorter menus, since every restaurant in town was forced to narrow its food options. No one seemed to mind, since anyone taking the time to dine out was simply happy the place was open. But if you sum it all up — the rules, the emptiness, the fear, the feeling of everyone being on guard — it's a wonder anyone bothered going out at all. But going out to eat is what we do, because it is fun, convenient, and delicious, and because we are human.

As Las Vegas's most intrepid gastronaut, I've had to curb my voracious appetite more than anyone. Overnight, my routine went from visiting 10 restaurants a week to a mere few. Even in places where I'm on a first-name basis with the staff, the experience is as suppressed as the voices of the waiters. Instead of concentrating on hospitality, the singular focus is now on following all the rules. All of which makes you appreciate how the charm of restaurants stems from the sincerity of those serving you — something hard to notice when you can't see their faces.

Nowhere are these feelings more acute than on the Strip. “Las Vegas needs conventions to survive,” says Gino Ferraro. “If the hotels suffer, we suffer.” He's owned Ferraro’s Italian Restaurant and Wine Bar since 1985, and he’ll be the first to tell you how thin the margins are for success in the business. Restaurants are in your blood more than in your bank account, and micromanaging, cutting costs, and (hopefully) another year of government assistance are what he sees as keys to their survival. “Good restaurants will survive, but there's no doubt there will be less of them.”

Unlike the free-standing Ferraro’s, the Strip is different. There, the restaurants are amenities — like stores in a mall, if you will — and from Sunday-Thursday (when the conventions arrived) they used to thrive. These days, like Ferraro's, they still pack ’em in on weekends, but almost all are closed Monday-Wednesday. This doesn't mean the food or the service has suffered — far from it — only that everyone is hanging on by their fingernails, and this anxiety is palpable when you walk through the doors. The staffs are almost too welcoming, which is nice, but you can sense the fear. It’s not pretty, and it is not going away for many months to come.

As Vegas slowly re-opens, one thing you can no longer take for granted is that each hotel will have a full complement of dining options, from modest to world-famous. If I had to make a prediction, it would be that a year from now, some hotels may field a smaller team of culinary superstars, and their bench will not be as deep, and those stars will have another season of wear and tear on them without any talented rookies to come along and take their place. Long before the shutdown, there were already signs we had reached peak Vegas and things were starting to wane. Some fancy French venues were showing their age, the Venetian/Palazzo (with its panoply of dining options) seemed overstuffed, and rumblings were heard that even the indefatigable David Chang had lost his fastball. The same could be said for the whole celebrity-chef trend, which was starting to feel very end-of-last-century by the end of last year. The Palms’ murderer’s row of newly minted sluggers was mired in a slump, and our gleaming, big box, pan-Asian eye-candy (Tao, Hakkasan) was not shining as bright as it once did.

♦

THE STAKES ARE much higher when you consider the reputation of Las Vegas as a whole. Survey the landscape these days and all you can ask is, how much of this damage is permanent? It took from 1989-2019 to take Las Vegas from “The Town That Taste Forgot” to a world-class, destination-dining capital — a claim to fame like no other — where an entire planet of gastronomic delights, cooked by some of the best chefs in the business, was concentrated among a dozen closely-packed hotels. Now, what are we? A convention city with no conventions? A tourist mecca three days a week? Can we recapture this lost ground, or is it gone forever? Everyone is asking, but no one has the answers.

Perhaps a culling of the herd was already in the works, and all COVID did was accelerate the process. Are the big-money restaurant days over? Certainly until those conventions return, and no one is predicting that until next year, at the earliest. If that's the case, it will be a leaner gastronomic world that awaits us down the road, not the cornucopia of choices laid before you every night. The fallout will include the casinos playing it safe; not throwing money at chefs like they once did, and sticking with the tried-and-true for a while. Less ambitious restaurant choices? Absolutely. It is impossible to imagine a single European concept making a splash like Joël Robuchon did in 2005, or any Food Network star getting the red carpet treatment just for slapping their name on a door. The era of Flay, Ramsay, Andrés, and others is over, and the next big thing in Las Vegas dining won’t be a thing for a long time.

If the Strip’s prospects look bleak, the resilience of local restaurants has been astounding. Neighborhood venues hunkered down like everyone else, but now seem poised for a resurgence at a much faster rate than anything happening in the hotels. If the Strip resembles a pod of beached whales, struggling to get back in the water, then local restaurants are the more nimble pilot fish, darting about, servicing smaller crowds wherever they find them. Four new worthwhile venues are popping up Downtown: upscale tacos at Letty’s, Yu-Or-Mi Sushi and Sake, Good Pie, and the American gastropub Main Street Provisions, all in the Arts District. Off the Strip, Mitsuo Endo has debuted his high-toned yakitori bar Raku Toridokoro to much acclaim, and brewpubs are multiplying everywhere faster than peanut butter stouts. The indomitable Chinatown seems the least fazed by any of this, and Circa is springing to life on Fremont Street, hoping to capture some of the hotel mojo sadly absent a few miles south. The bottom line: Look to the neighborhoods if you wish to recapture that rarest of sensations these days — a sense of normalcy.

Watching my favorite restaurants endure these blows has been like nursing a sick child who did nothing to deserve such a cruel fate. In a way, it's made me realize that's what they have become to me over decades: a community of fledgling businesses I've supported and watched grow in a place no one thought it possible. As social experiments go, the great public health shutdown of 2020 will be debated for years, but this much is certain: Las Vegas restaurants were at their peak on March 15, 2020, and reaching that pinnacle is a mountain many of them will never climb again.

HOW HEALTHY are you? You might answer the question with information about your weight, your diet, your blood pressure, your pre-existing conditions or chronic ailments. But just as important might be how much money you make, how you cope with stress, and how far you have to drive to the pharmacy or grocery store — or whether you drive at all.

In other words, there are more factors that determine your health than those that typically come to mind. This isn’t big news. But it’s unlikely that the last time you had a check-up the doctor asked, for instance, if you’re anxious about your family bank account and suggested talking to a therapist right there at the office — or connected you to a social-services worker onsite to discuss financial support programs.

The term for this more holistic approach to well-being is called “integrated healthcare.” The term is common in the more academic corners of health and medicine institutions, but putting it into widespread practice is a slow, sometimes complicated process. But many people and organizations in the valley are working to make it a reality.

click for more

In practice, integrated healthcare is pretty simple. For instance, at Volunteers in Medicine of Southern Nevada — an organization providing

healthcare for low-income patients — they distribute gift cards to help clients with their rent and groceries. It’s not a mere philanthropic perk. It typifies Volunteers in Medicine’s philosophy of considering the patient’s health more than just the state of their physical body.

“We can prescribe someone insulin all day long. But if they don’t have a refrigerator to put it in, or they don’t have a sanitary environment or the right foods to eat to help them to manage their diabetes, their situation isn’t going to change,” says Tabitha Pederson, chief operating officer of VMSN.

What does integrated care include? A better question is what doesn ’t it include? “It’s a list of things that impact someone’s health and their ability to live a healthy life, but these things don’t necessarily have to do with medicine,” Pederson explains. “It’s food, it’s legal issues, it’s transportation. It’s even the neighborhood you live in. It’s community violence. So we provide primary care, but also mental health services, social services, and dentistry, all in one building for our patients.” The VA Southern Nevada Healthcare System and Nevada Health Centers (a statewide nonprofit network of clinics serving rural, uninsured, and underinsured clients) also practice versions of integrated healthcare. But there are a few obstacles in the way of more widespread adoption of the practice.

One is education. Because integrated healthcare often requires collaboration between disciplines, practitioners have to learn to understand where their expert knowledge ends and where another’s begins — and when to pass the baton, so to speak. In the academic setting, learning how to deliver integrated, collaborative care is called interprofessional education. Roseman University of Health Sciences incorporates interprofessional education into its curriculum.

“In a nutshell, what we’re trying to do is move from being in our separate silos to a more integrated system to improve the health of our communities,” says Dr. Thomas Hunt, professor and chair of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Medicine at Roseman. “Interprofessional education starts with getting students of various disciplines into the classroom, working together, learning from each other, learning with each other. But we’re really trying to move that needle to interprofessional practice and education. So it’s great that you and I are from different disciplines and we’re learning together. It’s more important that we practice together.” For example, in Roseman classes that involve simulated patient cases, a pharmacy student and a nursing student assess and discuss the patient’s data, and then present it to the physician. “Then together, we work on a plan using each of our focuses so we can have a comprehensive plan of care for the patient,” says Hunt.

Notice how this is different than the usual flow-chart of healthcare, in which decisions typically come from the doctor. In integrated healthcare, a nurse’s assessment might turn up issues that a doctor might never consider. Hunt says, “(A nurse) might look into things like, what’s going on in your home? What are some of the extraneous factors that may be affecting your health? Where do you live? What neighborhood? What’s your transportation?” The term for these factors is social determinants of health.

UNLV also weaves interprofessional education into its curriculum. In 2014, the UNLV School of Social Work received a $1.4 million federal grant to educate social work master’s students in integrated healthcare. Over three years, the grant program trained 108 students on applying their expertise in integrated healthcare settings such as Volunteers in Medicine of Southern Nevada, with a focus on patients with chronic health conditions and mental health conditions. The grant program was considered such a success, UNLV made the integrated healthcare training a permanent course.

“I particularly love integrated healthcare because what we’re seeing is that when a person comes into treatment, usually the first place we’re going to see them is in the emergency room or their doctor’s office,” says Natasha Mosby, a lecturer in UNLV’s School of Social Work and program coordinator for the Integrated Behavioral Healthcare Grant. “The research over the past 20 years shows that if we can integrate that behavioral healthcare system right inside of those spaces, it results in better outcomes for those patients.”

As integrated care evolves, it takes many different shapes, some of which you might not even recognize as integrated care. Mosby gives an example. “When I take my kiddos to the doctor, I recently noticed on those little iPads that they’re asking questions about not just their development, but just their mood and temperament. I asked the doctor, ‘If I answer yes, that I’m having trouble comforting my kiddo at night or she’s having nightmares, what’s the next step?’ And the next step is that he gives this information to the nurses, who might connect us to services for my kid. It may be bigger than something just medical. Providers now are thinking about how they can provide patients with resources they need outside this particular setting.”

One other obstacle to integrated care is cultural — specifically, our collective tendency to lionize doctors as heroes and mavericks (just watch any network medical drama for that). Passionate dedication to care is admirable, but true integrated care also requires checking any egos at the door.

“It used to be that the doctor just barks orders and everybody tries to follow around,” says Hunt. “But we know that in integrated care, we all should have an equal say in what happens.”

ZACHARY CAPP IS a distinctively Las Vegas character. A former corporate CEO and a recovering gambling addict coming off a stint in rehab, Capp decided a few years ago to quit his job and pursue his lifelong dream of becoming a filmmaker, spurred into action by the death of his grandfather, who always encouraged Capp’s dreams (and left his grandson a sizable inheritance). As depicted in the entertainingly cringe-filled new documentary The Ringmaster, Capp set out to create his first film with little experience or planning. His first task after founding his production company Capp Bros? Get branded baseball hats.

click for more

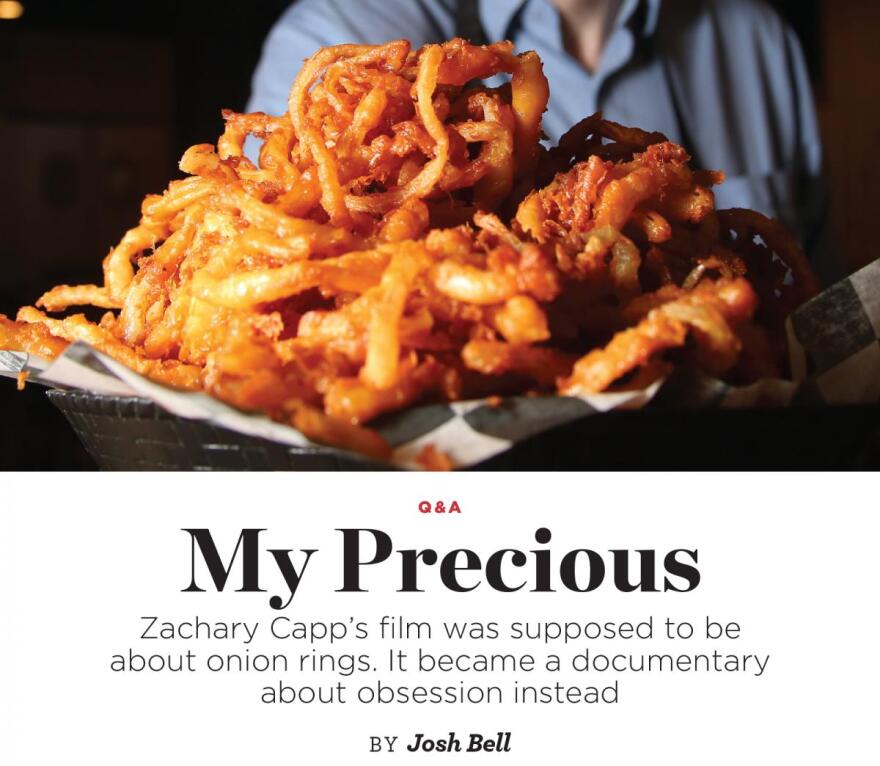

Thanks to his family’s Minnesota roots, Capp had grown up eating the onion rings created by Worthington, Minnesota-based chef Larry Lang, which diners (including Washington Post food critic Tom Sietsema) have proclaimed the best in the world. Capp decided to make a film that would introduce Lang’s onion rings to the world, despite the fact that Lang himself seemed ambivalent at best about the prospect of starring in a documentary. The Ringmaster depicts Capp’s years-long odyssey to document and promote Lang and his delicious onion rings, whether Lang wants him to or not. Similar to recent meta-documentaries such as David Farrier and Dylan Reeve’s Tickled and Ben Berman’s The Amazing Johnathan Documentary, The Ringmaster gradually evolves into a movie about its own making, as frustrated members of Capp’s crew (including ultimately credited directors Dave Newberg and Molly Dworsky) take over the production, turning the camera on Capp to document his increasingly desperate obsession.

The Ringmaster becomes a portrait of an addictive personality, of good intentions gone awry, and of a modest Midwestern chef who had no idea what he was getting into with this fast-talking Vegas impresario. It’s also still a little bit about onion rings, and there are glimmers of hope and connection amid the chaos. Persistently upbeat, Capp now fully embraces what the movie has become, and remains a champion of both Larry Lang’s onion rings and his own burgeoning film career. Fifth Street interviewed Capp about his new film.

What's the experience of watching the movie like for you?

Well, I lived it for over three years of my life. But watching it come together was definitely a fascinating experience. It wasn’t the film that I originally set out to make, by any means. But in the end, I think we made the most compelling story possible. Life is not a straight line, you know? It’s full of ups and downs. Even though there are those uncomfortable moments, I think it kind of balances with a lot of heartfelt moments. It’s funny, too.

Was there a specific point during the process when you felt like you relinquished control of the project?

It was always my project, but in terms of the direction, the creative direction of the project — I was kind of blinded by my own ambition making this movie. Basically I broke the cardinal rule of filmmaking while making this movie. I got too close to the subject of my film, and I became more focused on creating a happy ending for this man and his onion rings, who I thought deserved more. Once the crew mutinied against me, I guess you could say, it was definitely difficult for me to come to terms with what they were presenting me with. They kind of showed me that what I was doing behind the scenes was more compelling.

Did you have to deal with additional counseling for the addictive nature of your focus on Larry and the movie?

I’ve always been very committed to my recovery. Even after this movie, during this movie, after rehab. I go to Gamblers Anonymous meetings regularly, and I have a strong support system. That’s something I’m always committed to. This movie, I really hope it encourages people with addictions, or whatever their “-ism” might be, to open up about it. Because I think this movie’s really honest. It was definitely difficult for me to show a piece of my soul to the audience here, and be so personal.

Has Larry seen the movie?

I'm happy to report, Larry and (his sister) Linda were able to attend our screening at the Twin Cities Film Festival in Minnesota. Thunderous applause. They loved the movie. They've watched it over 100 times now. That to me means more than what anybody else thinks.

Given the tensions between you and your collaborators shown in the movie, were there any relationships that were permanently damaged?

No. Honestly, I think this whole experience brought us closer together. I think that's a sign of how strong the friendships are. We're all close, even (producer and editor) Sean (Brogan). I know we had a falling-out in the movie. Him and I, we talk every day. He's one of my best friends. He actually cut the trailer.

What was audience response like when the movie played at film festivals?

Every time we played, it was like a visceral experience for the audience. It really was received very well everywhere we played. Thunderous applause. I think people really appreciate how honest this movie is. I like to say this movie is just like an onion. There are so many layers to this story. It’s got the full spectrum of emotions in there. You feel everything.

Do you see this film fitting in with the current trend of meta documentaries?

Absolutely. I think this is the most meta documentary ever made. I'm pretty sure it is. This is ultimately a film about filmmaking.

What was the biggest lesson you personally took away from this experience?

Just be true to yourself. Just be honest. I think I learned so much about filmmaking while making this movie. Preparation is key. Doing research is key. I could have made it much differently, but the fact that I made it the wrong way is what makes this film unique, what makes it so compelling. That’s why it’s been resonating with audiences.

Are you still hoping to pursue a career in filmmaking?

Absolutely. But I don’t know about documentaries, to be honest. If I do something else, I think it will be scripted, and it will be something lighthearted. Maybe something for Hallmark, something along those lines, I’m thinking. Because this was an intense experience, as you can imagine. I’m not shutting the door on documentaries. But filmmaking and telling stories have always been my passion, and I continue to pursue that.

The Ringmaster is available now on all major VOD platforms. A portion of all proceeds benefits Alzheimer’s research.

"WHOSOEVER IS DELIGHTED in solitude,” Aristotle tells us, “is either a wild beast or a god.” I’m pretty sure I fall somewhere in between, even if my personal habits have inclined toward “wild beast” since WFH began. (If I were a god, you’d know it from all the smiting.) But A-Tots has nailed me on one point: If not actually delighting in this solitude — it’s hard to delight in anything at a time of plague and disruption — I am readily adapting to it. Overadapting, you might say, especially if you’re my wife. (“You never want to go anywhere.”) An introvert, I’m leaning into quarantine, and not only because it’s made long pants optional. No, my deepest psyche is comfortably nesting in this newly expanding gap between contact and disconnection. “The longer I go without people,” writer Howard Bryant said recently, “the less I need them.” Hard same.

click for more

But is this a good thing? I’ve seen plenty of think pieces about the detrimental effects of social isolation. About the depression, anxiety, and loneliness millions are enduring while cut off from family, friends, and even strangers. In a recent New York Times Magazine essay about visiting Turkish baths before lockdown, writer Leslie Jamison turned her experiences into a lament for the lost upside of random social friction in a cosmopolitan society: “When we lose the ability to live among the bodies of strangers, we don’t just lose the tribal solace of company, but the relief from solipsism ...” You can’t Zoom your way out of those problems.

But I haven’t seen much about the pitfalls of really burrowing into this newly licensed solitude. Of embracing it in a way you couldn’t back in the olden days of earlier this year, when work duties and life-structuring social obligations still forcibly extruded you into the world. What does it mean that while I miss lunches with friends, I’m content to skip pretty much everything else that involves group dynamics and small talk? Sorry, can’t make it, I’m trying to win quarantine. In April, I emailed a friend: “When it's over, will I even want to reemerge?” Now that society is letting me be the hermit I never thought I could, are there effects I should watch out for? I’d rather not end up in a cabin, wearing an embarrassing beard, and typing antisocial manifestos.

Here’s someone we can ask. Stephen Benning is a psychology professor at UNLV, where he directs the Psychophysiology of Emotion and Personality laboratory, using the methods of science to probe the murk of human feelings. He didn’t find the behaviors I described particularly worrisome. “That kind of introversion is just one pole on a normal-range introversion-extroversion dimension of personality.” (Note to wife: normal range.) Indeed, because ours is a culture that prizes gregariousness and social charisma, it would be surprising if introverts didn’t treat quarantine — a rare moment in which society has realigned along their axis — as a respite and an affirmation. As one Vice homebody wrote, “It seems ridiculous that the marvels of social distancing are only getting recognized in the face of a global epidemic.”

Don’t take introversion to mean “dislikes other people,” by the way. Introverts simply set tighter preferences on their social inputs. Some studies indicate it may have to do with brain chemistry — differences in dopamine sensitivity could explain why extroverts respond to the boisterous energies of the group, while introverts are drained by the effort to make nice. “It’s not necessarily that people who are introverted hate social gatherings and other such things,” Benning says. “It’s just that they’re more taxing.”

Still, most of them need some quotient of human encounter, including the ungoverned, everyday kind Jamison writes about. Benning suggests that now, freed from the pressurized communal obligations of the past, introverts might use this period to game out new routines for errands, meetings, and so on that allow for tolerable levels of interaction.

Unless they possess a Unabomber-grade solipsism, even the homiest of homebodies might find a protracted shelter-in-place scenario too much of a good thing, and will nudge themselves back into the social world. “The kinds of people who might run into greater trouble reintegrating ... are the kinds of people who are more than just introverted,” Benning says. “They may be people who are interpersonally detached.”

Which doesn’t sound like me. So, rather than a feeding a budding pathology — Scott was a quiet guy, who kept to himself — my happy solitude just means I’m subsiding into comfortable behaviors made tenable by our new normal. Benning: “We often say in the personality literature, as long as your traits aren’t too strong, it’s likely you’ll be pretty flexible in negotiating the world.” Which means some day I’ll have to put on pants again, if I can remember where my head goes.

Photos and art: Dining: Sabin Orr; Healthcare: Christopher Smith; Ringmaster: Courtesy Zachary Capp; Introverts: iVector/Shutterstock.com

Subscribe toFifth Street and get news, profiles, commentary, and humor in your inbox every week.