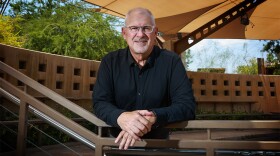

A climber with real altitude

The trial: While racing in an Over the Hill motocross competition in Orange County in December 2001, 43-year-old Dan Young landed a jump much too hard, shattering both his ankles. His ambulance ride from the track to the ER began a four-year ordeal that included multiple surgeries, one with complications causing blood clots to move from his legs to his lungs, nearly killing him. After the right ankle refused to heal, Young got a second-opinion suggestion of amputation, but opted instead for total fusion of that joint. Young’s injury condemned him to a life of pain management and arthritis in both ankles. “I lost my wife, my home, my job,” he recalls.

The triumph: “… but a few years into it, I was ready to walk again,” he adds. Preparing for a job interview for which he was determined not to use his wheelchair, Young went to an Army Surplus store and bought a pair of what he calls “very supportive” boots. They did the trick, enabling him to enter the interview on his own two feet. It wasn’t long before he was back in his beloved outdoors, first biking, then hiking and finally rock climbing, using special ankle braces he still wears under his shoes. Young celebrated his recovery by climbing Mt. Rainier in 2008.

Today: Now 54, Young says he’s “semi-retired and loving it.” He left his real estate development career and guides rock climbers at Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area. “He’s got a great attitude — that of a very able adventurer,” says friend and fellow climber Sue Schager. “If I did not know of his injuries, I certainly would not suspect he is disabled. In all of our rock climbing and mountaineering adventures, I have never heard him speak of what he’s not able to do.” Although Young acknowledges that his abilities will dwindle and his pain increase over time, he says the day when he succumbs to a sedentary life is “a long way off.” — Heidi Kyser

Unstoppable optimist

The trial: In the space of five weeks in the fall of 2009, Collins lost a sister to breast cancer and her mother to uterine cancer. Her remaining sister had been undergoing treatment for breast cancer that year, too. In May of 2010, it was Collins’ turn. Three months after being laid off from her job at a communications company, she found a lump that was diagnosed as stage 2, grade 2 breast cancer.

The triumph: Over the following months, Collins underwent chemotherapy, two separate surgeries and radiation therapy. As soon as she was able, she jumped into every activity she could find. To alleviate the bone and muscle aches caused by chemo, she began walking every day with her neighbor Holly Davis. She joined After Cancer Treatment, a women’s survivorship group, and ended up competing on its dragon boating team. She went to a nonprofit called The Caring Place for art therapy and now teaches classes for kids there. “That is something I can’t imagine me doing before cancer,” Collins says. “I find that I am more open, with all that I have been through.”

Today: Collins is hitting the pavement with plenty of resumes and even more resolve to find a job. Neighbor Davis says she’d be surprised if the dismal employment scene in Las Vegas got Collins down. “She has the fortitude of an ox,” Davis says. “Out of the entire time she was going through treatment, there were only one or two times she couldn’t walk with me. I had just had a baby, but I figured if she can do it, with what she’s going through, I have to be there for her every day, no matter what.” Davis nicknamed her “Determinacia.”

“If I could go back and choose whether to go through it again, would I?” Collins says. “Hell, yes. It has made me who I am today.” — H.K.

Back from the crash

The trial: When Candace Jones came to after the crash, she first touched a painful knot on her forehead: Blood. Gee, hope I don’t need stitches, she thought. A bump on the head would be the least of her problems. Still in shock from the car accident, she didn’t realize the impact fractured her spine’s L3 vertebrae and tore open her kidney, liver and intestines. It was her first semester at George Mason University, and a teenage drunk driver cut short her night out with friends on Valentine’s Day in 2002 — and changed her life. “My world crumbled,” says Jones, who was an avid swimmer, runner and soccer player. “I was 18, I had just started college, and I was finally free for the first time. Then all of a sudden I’m back at my parents’ house, and I’m dependent on my mom to feed me and shower me.” (Insult to injury: an elaborate spinal brace that earned her the nickname “Robocop.”) During her year of recovery, doctors told her that running again would be a bad idea.

The triumph: Hold the inspirational music montage. Jones’ comeback was careful, methodical, judicious. “I thought, how am I going to turn this situation around? What story will I someday be telling people about how I handled this?” Jones applied a timeworn principle of running: Sometimes slow and steady wins the race. After a semester off, she re-entered college with a 12-credit load to stoke her motivation. She declined spinal surgery, counting on her vertebrae to fuse naturally. By June 2003, she enrolled in women’s soccer. “I always knew she was a strong person,” says longtime friend Kristina Myers. “But it blew me away how determined she was to get better.” It wasn’t long before Jones was tying on her kicks and hitting the trails again.

Today: “The accident put things in perspective. When I’m in a race and I’m getting tired, I tell myself, ‘You survived a terrible accident and came this far — don’t give up now!’” Today she’s sponsored by Snickers Marathon bars, and competes in as many races as her schedule as a wife and mother of two allows. In May, she took first place in the 10k Mums on the Run race. Her counsel for getting back into the groove: patience and perspective. “No matter how fast or slow you’re going,” she says, “remember that you’re still lapping everyone sitting on the couch.” — Andrew Kiraly

Taking a chance

The trial: As a young girl, Kassidy Merritt often had hiccups. Her parents blamed balance issues on clumsiness. And the doctor wasn’t too concerned about a mild case of precocious puberty. Then, in the fall of 2010, the 15-year-old honor student and catcher for Centennial High School’s softball team began having breathing problems. By December, headaches. In January, vomiting. In May, just as Merritt’s softball team was headed to state playoffs, she was diagnosed with a rare, cancerous and inoperable brain tumor called ganglioglioma. “They said I was probably born with it,” she says. Radiation was prescribed; if that failed, chemotherapy. Because the tumor was in Merritt’s brain stem, the side effects were expected to be severe. She would likely need a tracheotomy; there would be burning of the skull; and possibly problems walking, talking and breathing. Merritt put down her catcher’s mitt, as well as her dreams of playing college ball.

The triumph: She and her parents discovered the Burzynski Clinic in Houston, where Dr. Stanislaw Burzynski employs something called antineoplaston therapy. It uses human DNA, including natural peptides found in the blood and urine, to supposedly trigger the death of cancer cells without inhibiting normal cell growth, but it’s controversial: A 2004 medical review declared it disproven; prominent oncologists say the research is flawed; and the American Cancer Society warns against relying on this treatment alone. Despite this, Burzynski’s clinical trials are in the final phase of the FDA approval process.

Today: A year later, Merritt is happy with her decision. “I wouldn’t change it. I wouldn’t do radiation.” She says that in the first 12 weeks of treatment, Dr. Burzynski discovered a 20 percent reduction in the size of her tumor. It’s remained stable since. Today, she says, less than 3 percent of her original cancer cells remain. Dragging around a backpack containing medicine administered via a port catheter to her chest is Merritt’s primary complaint. Although the therapy inflamed many of her original symptoms, and steroids prescribed to treat these gained her 60 pounds, Merritt’s been able to keep up with her schooling, coach softball, and even train a little with a club team. She’s due to continue treatment through January. “Even when she’s off the medication she will still have some symptoms, because she has a foreign body in there,” explains her mother, Massiel.

Will she play ball again? Oh yes. “When I lose the backpack.” — Chantal Corcoran