There was nothing left of his home but cinders when young Douglas LaVan Martineau returned late at night on August 6, 1950, from a Boy Scouts camping trip.

Like his mother who’d died eight years earlier at the age of 32, his father (also named Douglas) was an alcoholic. He had been drinking in the living room and left a lit cigarette on the couch before retiring. That night the local fire department was having a convention in town, so no one responded to the blazing house in Cedar City, Utah.

As Martineau wrote in the preface to his masterpiece on rock writing, The Rocks Begin to Speak, there is not a Paiute word for ‘orphanage.’ Following the funeral, a one-armed Paiute man named Edrick Bushhead told him, “Come stay with me and be my son.” Other Paiutes quickly volunteered as additional foster parents — Maimie Merrycats and James and Mabel Yellowjacket from the Cedar Band, and Wendel John from the Shivwits Band. One of his daughters, Shanandoah (Shanan) Anderson, says his new extended family taught him sign language, dances, beading, how to make bows and arrows, and how to tan hides, all while he was finishing Cedar City High School. Although he was white, he thought of himself as a Paiute, a “reverse apple — white on the outside and red on the inside,” Anderson recalls.

When Martineau turned 19, he and his Paiute friends decided to enlist in the Air Force rather than be drafted into the Army or Navy. “What are your skills?” the recruiter asked. “I can herd cattle,” he replied. “If you can do that, you can herd airplanes.” Dispatched to Korea in 1951 to serve as an air traffic controller, he shared a Quonset hut with the cryptography department, where seven of his tent-mates worked as codebreakers. It wasn’t long before he realized that he could use many of the same principles and methods to help decipher the ancient petroglyphs (engravings or etchings) and pictographs (paintings or drawings) he’d grown up seeing on rock faces in the desert Southwest.

After he left the Air Force in 1959, Martineau decided to devote the rest of his life to cataloging and interpreting this “rock art,” the popular name for images left by people who lived hundreds or even thousands of years ago. Paiutes and other tribes prefer that it be called “rock writing” for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is that it was not intended to be decorative but to tell a story using universally comprehensible symbols.

But that same rock writing, sacred to Indigenous Peoples and critical to understanding ancient cultures, is being slowly destroyed. As urban development and outdoor activities such as off-roading and tourism affect natural areas throughout the Southwest, graffiti and trampling are becoming more commonplace at cultural sites. Panels that Martineau catalogued so meticulously and archaeologists have studied for so long have been damaged. Will they still be here in a thousand more years, for others to learn from and connect with?

In 2018, Nevada Highway Patrol Troopers pulled over two 28-year-old Elko men who were covered in blue paint and had 100 spray-paint cans in their car. A news release from the United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Nevada described how the pair had painted graffiti at several locations at White River Narrows in the Basin and Range National Monument in Lincoln County, including over a rock face with petroglyphs sacred to the Paiute and Shoshone tribes. A witness to the crime called the police. One of the men was sentenced to six months for misdemeanor conspiracy and a year-and-a-day imprisonment for felony violation of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act. The other was sentenced to four months’ imprisonment for misdemeanor conspiracy followed by eight months of home confinement. U.S. Attorney Jason M. Frierson for the District of Nevada said, “This ruling demonstrates that such crimes will not be met with a slap on the wrist. Our office will continue to work to ensure that anyone who desecrates sacred tribal lands and artifacts are (sic) held accountable.”

Part of the problem with calling rock writings “art” is that doing so implicitly encourages such defacement, says Daniel Bulletts, the Kaibab Band of Southern Paiutes’ cultural resource director. Vandals might think to themselves, “Maybe I could put my art up there next to (theirs) to see how many millions of years it lasts,” he says.

Archaeologist Kevin Rafferty, a College of Southern Nevada professor emeritus, has studied rock writing for more than 30 years. He estimates there are 1,700 sites in Nevada, seen by more and more individuals and families all the time. News outlets widely reported on the skyrocketing outdoor recreation during the pandemic, as people looked for activities they could do while socially distanced. Younger generations continue to show increasing interest in the outdoors. Terri Janison, Friends of Red Rock Canyon’s executive director, regrets that the 13-mile Scenic Drive there had to be closed a few times in 2022, but says Red Rock is being “loved to death” by close to 4 million visitors annually, as many as Zion National Park in Utah receives. Of course, among these crowds are some criminals, who etch their initials or spray-paint words over petroglyphs and pictographs. Or worse …

Eddie Hawk Jim of the Pahrump Band of Southern Paiutes says the petroglyphs around Mt. Charleston, located in the Paiutes’ revered ancestral lands known in English as the Spring Mountains, have been destroyed by off-roading and spray-painting. In 2008, a 58-year-old man removed a 300-pound boulder with a petroglyph showing seven sheep and placed it in the front yard of his Pahrump home. An April 2011 news story in the Pahrump Valley Times reported that the vandal was sentenced to six months in federal prison and one year of supervised release.

Rock writings in the highly visited Red Rock are also suffering. Last year, graffiti was discovered along two hiking trails, the first at Lost Creek and the second at Calico II. From pottery artifacts discovered there, it’s believed that the area was occupied by Ancestral Puebloans and then Paiutes at least 1,000 years ago, and possibly by Paleo-Indians as early as 11,000 B.C.

In May 2011, the Red Rock Canyon Interpretive Association and Bureau of Land Management asked Stratum Unlimited, led by archaeologist Johannes (Jannie) Loubser, to mitigate graffiti on 17 rock panels at Lost Creek. In one instance, graffiti had been left directly on top of a pictograph. Loubser returned to lead a graffiti removal workshop at Lost Creek and Calico II in 2014. In all, he has removed graffiti from three sites at Red Rock, four sites at White River Narrows, one site near Alamo, and one site near Reno/Sparks, and he has assessed nine other sites.

Too often, Loubser says, well-meaning but untrained conservationists whom he calls “graffiti vigilantes” damage rock writings even more. “Less is more” best describes his method of remediation: using the least invasive techniques for removal first to prevent further damage. Several mechanical and chemical techniques must be pretested on similar rock surfaces elsewhere and in a certain order depending on the particular surface. If graffiti can’t be safely removed, it can be camouflaged, he says.

But an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of remediation, camouflage, or prosecution. Madeline Ware Van der Voort, the BLM’s state archaeologist and preservation office deputy, echoes many in the preservation community when she says that education is key. In this, too, Martineau was a pioneer. He spent more than 40 years studying and interpreting the symbols etched and painted on rocks so that other people might better understand the stories written there and thereby respect and preserve them.

The Peoples Behind the Pictures

Beginning after his Air Force service, Martineau drove across the United States, Mexico, and Canada to sketch, photograph, and prepare site maps of rock-writing panels. He documented petroglyphs and pictographs at hundreds of sites across Nevada and elsewhere in North America, taking more than 25,000 photographs. At first he traveled by himself and then later took his daughter Shanan Anderson, who helped him compile eight thick notebooks of pencil drawings of symbols with descriptions as detailed as any prepared by contemporary site stewards.

Anderson remembers driving with her dad from powwow to powwow or tribe to tribe, accepting free meals and earning gas money by selling arrowheads that Martineau carved while sitting on the tailgate of his truck, a curious crowd gathering around him. It was a simple, nomadic lifestyle that culminated in Martineau’s best selling book as well as a 1992 coauthored work titled, Southern Paiutes: Legends, Lore, Language, and Lineage. By the time he died of colon cancer in 2000 at the age of 68, Martineau had become a legend. Anderson, who went on to marry into the Moapa Band of Paiutes, is now working with an artist to publish her father’s notebooks as one large volume, which will enable today’s archaeologists to compare the state of rock-writing panels in the late 1950s to early 1970s with their present condition.

Central to Martineau’s work were the same questions that have perplexed archaeologists and anthropologists throughout time: Who made these rock writings and when? And what were they saying?

There is general agreement that the Pyramid Lake Paiute Reservation northeast of Reno holds the honors of oldest American rock writing. Researchers think etchings in boulders there are at least 10,000 and perhaps 15,000 years old. They are rivaled by a few Mojave Desert sites in California; much depends on the dating techniques used (more on that later).

One of Kevin Rafferty’s favorite research haunts in Clark County is the Valley of Fire State Park, specifically Petroglyph Canyon on the trail to Mouse’s Tank. Rafferty says the area was used by humans at least 7,500 years ago but was more occupied 2,000 years later by the Archaic peoples, then the Ancestral Puebloans, and finally the Paiute and Patayan cultures about A.D. 1100-1200. Rafferty ventures that the majority of the fresher-looking petroglyphs that contain a large number of representational motifs (bighorn sheep, humans, possible insects) could be tentatively dated to roughly the years 300-1200. The more abstract ones are probably Archaic age (3500 B.C.-A.D. 300). Some anthropomorphs (human-like figures) with splayed fingers and any H-shaped motifs are probably Patayan (precursors to modern-day Lower Colorado peoples) dating from about A.D. 900, while anything that is scratched into the rock as motifs and much of the pictographic (painted) record are likely Paiute, dating from A.D. 1100 forward.

Native Americans originated in Eurasia and migrated across the land bridge linking Asia and North America. Two separate scientific DNA studies from about four years ago showed that ancient populations then spread across the Americas some 13,000 years ago.

One problem with using DNA from bones unearthed in archaeological excavations for genetic studies is that it violates the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, passed in 1990. With that in mind, UNLV anthropology professor Karen Harry could not contain her excitement when talking about upcoming research in Southern Nevada. Beginning about 1500 B.C., the Ancestral Puebloans would extract fibers from agave and yucca leaves and compress them into small wads called quids for chewing or sucking on. The DNA from their saliva is still often viable enough to be sequenced, and use of saliva does not violate NAGPRA. Harry and her graduate students intend to sequence the DNA from eight or more quids collected at a site outside Kanab, Utah, then compare that DNA with other DNA from the same time period in Southern Nevada to find out whether migrants introduced agriculture or local peoples started farming themselves. It will also help to determine how the Ancestral Puebloans are related to modern tribes.

Beginning about A.D. 750, populations swelled and villages developed, culminating in irrigation systems for growing corn, beans, and squash; large, underground rooms known as kivas that were used for social occasions and spiritual ceremonies; the beginnings of jewelry-making with turquoise and shells; and development of trade routes. Over time, the individualistic worldviews in the early cultures of the Great Basin (comprising the Mojave Desert, Owens Valley, and Nevada) gave way to more collectivist values, says UNLV anthropology doctoral student Manuel De Cespedes. Rock writings reflected this cultural shift, changing from abstract to representational images of humans and sheep.

Shamans (medicine men) were depicted in rock writing as having horns, representing the buffalo and bighorn rams that gave power to them, Anderson says. They held key positions in Indigenous communities and were responsible for most rock writing from about A.D. 50 until collectivist values emerged with larger villages and towns at the end of the first millennium.

Archaeologist David Whitley, who has studied and written extensively about shamanism, says, “In the Great Basin, the chiefs and the shamans were the same people. There you see the position of religious authority is tied to a position of political power.” Initiations into shamanism, traditionally reserved for males, required years of preparation culminating in a drug-induced vision. Trances could be brought on by isolation or sensory deprivation, stress from fasting or pain, dancing, or hallucinogens such as jimson weed and native tobacco, “which has eight times the nicotine content of Virginia Slims,” Whitley quips.

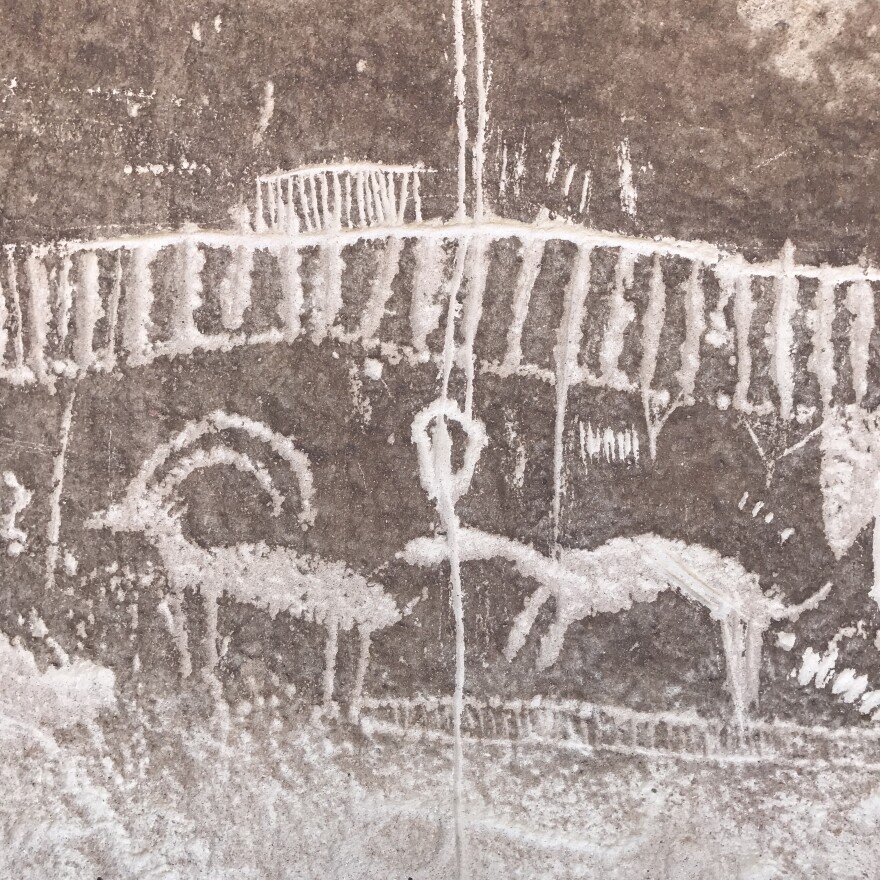

He argues that shamans sought out rocks, caves, and water sources at night to enter the spirit world and obtain supernatural powers to cure (or cause) illness, pray for rain, bring about good luck, find lost objects, and battle evil shamans. When dawn broke, they would etch images of their visions on rocks at these sacred sites, leaving petroglyphs in the rock varnish, which is a coating of clay minerals and/or oxides left on the surface by weather over time. The tools used to etch or “peck” through the varnish to expose the lighter layer underneath were hammerstones of quartz or other minerals, knives, or chisels. Quartz was thought to confer supernatural power to the petroglyph because when struck it generates a flash of light, adding drama for onlookers.

As paint for pictographs, shamans mixed hematite for the red hues, kaolin clay for white, and charcoal or manganese oxide for black. To bind the paint after it dried, the artists added plant resins, animal blood and fats, or a liquid such as water. If water was not available, saliva or urine was substituted. Common pictographs were handprints, made during ritual puberty ceremonies for both boys and girls.

Dating a History

Rock writing is as old as Stone Age cave art found in Europe and Australia beginning about 3.3 million years ago and extending to the end of the Pleistocene about 11,650 years ago. On this basis and also Native American origins in Eurasia, Martineau suggested that if Native American pictography is eventually proven to be identical to the original Old World system, then “it represents the survival of the actual parent system of almost all writing right up until the beginning of our modern era.” In consulting the elders of tribes across North America and studying cryptanalysis, he discovered there was a universal sign language that “overcame the difficulties posed by extreme differences in (spoken) languages. The symbols for passing through, water, in front, and coming down bear close resemblances to movements for such concepts in the sign language,” he wrote.

Given what researchers know about Ancestral Puebloans and their culture, how precisely can they pin down the date(s) of any given rock writing? Not very well — but they’re getting better at it. One limitation is the need to avoid damaging the panels in any way. Also, more than one time period is often represented at a site, though this may sometimes offer clues. One example is the 300 rock writing panels with 1,700 designs at Sloan Canyon in Henderson, which archaeologists believe span the Archaic era to about 200 years ago. Kevin Rafferty points out that on one panel there, a man with a hat is depicted on horseback. It could refer to someone like Jedediah Smith, a hunter and trapper who crossed the territory that is now Nevada in 1827 on his way to or from California. Or, it might reflect the 1776 expedition of Fray Francisco Hermenegildo Garcés, a missionary priest who was the first known European to visit the territory currently known as Nevada.

Identifying a design’s subject matter, such as a man on horseback, is the most common method to date an individual design safely. Horses with riders appear in petroglyphs throughout the Great Basin and California, Whitley says. Bows and arrows, which were introduced about A.D. 500, provide another example. Before that, Ancestral Puebloans hunted with a spear and wooden spear-thrower called an atlatl to give it more momentum. The spear had a conical depression that fit into the hook of the atlatl. A hunter would raise the atlatl over his head in an arc and send the spear off to its target some distance away. Some panels on Atlatl Rock at the Valley of Fire clearly show hunters holding an atlatl, meaning those petroglyphs were etched prior to A.D. 500.

Another nondestructive way to gauge the age of rock writing by relative dating is to assess the condition of a pictograph. If it’s more degraded or fainter than another, it’s possibly older. Although a number of weather-related variables can lead to wrong conclusions, this method is less prone to error if it is cross-checked using other methods.

Whitley and Arizona State University geography professor Ronald Dorn have been using three chronometric methods to date the rock varnish over petroglyphs. Before 11,000 years ago, the environment was wetter and less dusty here in the West, producing a varnish that is now rounded and lumpy. But since that time, the drier, dustier conditions produced a flat or lamellate varnish. To date pictographs, the only method used so far has been radiocarbon-dating of organic matter in the pigment binder mentioned above. Combining two or more relative dating and chronometric techniques has led to more robust conclusions about age.

Past is Prologue

Martineau’s book has been reprinted many times, and as a result he was asked to give talks and consult with several tribes. Anderson says, “He received criticism in the white world because he was a white guy teaching Indian writing and had never attended college. He was put down a lot, but he didn’t care because he was raised reading it.” Some Indigenous People tested his knowledge, too. Anderson recalls one tribe in Arizona inviting him to see if he could read a panel of petroglyphs. He told them it was a map to a battle site. They confirmed it and led him down a path to where the battle occurred.

How should we decipher and interpret petroglyphs? What was the creator trying to say? Humans can’t help but interpret apparent messages left by other humans, but modern people can easily misinterpret the symbols of ancient peoples. For instance, we might jump to the conclusion that the image of a man holding an atlatl above his head with a deer or bighorn sheep nearby is describing a hunting episode or conveying the news that it is a good hunting ground. But we would be imputing our 21st-century experience to something that could bear no relation to the culture of the Ancestral Puebloans. “If they emphasized what they were eating in their rock art, walls would be covered with bunny rabbits,” says Whitley. (They’re not.)

Martineau would likely agree. He pointed out that hunting was so common that it was not worth celebrating except for the unusual hunt or animal. More telling is the fact that sheep were almost never depicted dead on their backs. Rather, he argued, sheep and deer symbols were used to express action or direction. To what? Water, of course.

In the desert Southwest, water has almost always been the most precious commodity. Droughts were especially widespread in western North America in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries and lasting for as many as 70 years, precisely the times when many rock writings were created. The search for water was responsible for continuing migrations within and out of the Great Basin for at least two millennia and probably much longer. Anderson interprets one panel on Atlatl Rock at the Valley of Fire as shamans sending their prayers for rain heavenward. David Whitley inferred from comments by the Numic-speaking peoples (Shoshone and Paiute tribes) that petroglyphs of Great Basin bighorn sheep depicted the spirit helpers of rain shamans. Immediately after a rain, sheep knew where desert plants would be sprouting. It was then possible to predict rain by bighorn movements, confirms James DeForge, executive director of the Bighorn Institute in Palm Desert, California.

Whitley contends that other animals were portrayed as spirit helpers as well — birds, amphibians, insects, fish, and reptiles. Rattlesnakes were the helpers of rattlesnake shamans, who could cure snakebite and handle snakes. Lizards crawling through cracks in the rocks and frogs jumping into the water represented the shaman’s ability to travel seamlessly between natural and supernatural worlds. Anthropomorphic figures are usually of shamans with elongated bodies and heads sometimes topped with headdresses.

Abstract designs are more difficult to interpret, Whitley says, and in many cases depict any of several entoptic images (geometric light images in our optical and neural systems) perceived during shamanic hallucinations. These include grids; dots, circles and flecks; concentric circles and spirals, parallel lines; zigzags and diamond-chains; meanders; and nested curves. Zigzags likely represent the tracks left by a sidewinder, while diamond-chains resemble the pattern on the back of diamondback rattlesnake. Concentric circles and spirals represent whirlwinds that could concentrate supernatural powers and carry the shaman into the spirit world. Humans (shamans) were commonly portrayed with heads of concentric circles or spirals instead of facial features.

As for why rock-art creators did their work to begin with, Anderson believed the primary function was to preserve, to hand down a library of storied rocks. Daniel Bulletts says, “It depicts a story that that person saw, something that he was hunting, something he came across. Each year that person came back to the same spot and added to that story. And other people that visit can read who did what and where certain things are and if this was good area to either harvest or hunt. It was not the domain of just shamans, as some say. That is more of a modern-day interpretation.”

Kevin Rafferty feels rock-writing creators were probably trying to depict relationships between man and the spirit world. Whitley is more explicit in that regard: “The rock-art motifs were more like pagan idols in the sense they had power. I’ve had informants tell me that if a rock-art panel is destroyed, it will release horrible sickness all over the world. But then they become important for a variety of other things. For one, they become images that serve in development of individual and group identity. People would be taught to respect, to consider sacred these sorts of things. Rock-art sites were recognized as places of supernatural power. They are potentially useful for curing yourself and getting better luck, so people would go to rock-art sites to pray and meditate.”

Professor Peter Welsh and art conservator-editor Liz Welsh of the University of Kansas, authors of Rock-Art of the Southwest, argue that rock writing may have been meant to convey all these things — and more. “I feel that Indigenous People have more at stake in the interpretation of sites, linked as the sites are to evidence of ancient occupation and, therefore, to ongoing rights,” Peter Welsh says. “Archaeologists are asking different questions of the sites, so folks tend to talk past each other. Yet, I have also experienced very encouraging collaborations.”

Writing the Future

Collaborations with parties beyond Indigenous communities and the scientific world will be required to preserve the rock writing Martineau dedicated his life to documenting. Some two-thirds of Nevada, 48 million acres, is public land, most of it managed by the BLM. Van der Voort outlines her agency’s current initiatives to protect rock-writing sites and educate the general public to engender respect for them.

Each of the six BLM districts in the state has one or more field offices, and each of those is assigned a staff archaeologist, she says. Site-monitoring, inspections, and patrols alert the BLM to vandalism. The Archaeological Resources Protection Act, applicable to sites more than 100 years old, is the main instrument for protection. If a new site is discovered, the BLM will sometimes withhold the locality from the public or, if it meets any of four criteria, nominate it for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. In the case of rock writing, the most relevant criteria are that it 1) represents distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction, or 2) is likely to yield information important in history or prehistory.

“Education is the key,” Van der Voort says, citing the example of Project Archaeology, a Northern Nevada program meant to foster understanding of past and present cultures. The Nevada Site Stewardship Program run by the Nevada State Historic Preservation Office trains volunteers to monitor archaeological sites on a quarterly basis and report any vandalism. John Asselin, public affairs specialist of BLM’s Southern Nevada District Office, is part of the team working toward the opening of a permanent Visitor Contact Station at the Sloan Canyon National Conservation Area early this year to replace the one destroyed by vandals at the beginning of the pandemic. Five bands of the Paiute Tribe and five other tribes are assisting in the interpretive plan for the station. Asselin says the BLM is also cooperating with tribes at Gold Butte National Monument to educate people on why the cultural sites there are important.

At Basin and Range National Monument in Lincoln County, archaeologist Robert Hickerson says 30 site stewards monitor 30 rock-writing sites dating up to 4,000 years ago, including several at White River Narrows. Alicia Styles, monument manager, adds that there is a Friends group there, along with two field rangers and a supervisory manager, to oversee sites. “We have installed interpretive kiosks to talk about the value of the resources and how to protect them,” she says. “We have a 3-D model website on prehistoric rock art that allows visitors to virtually explore and appreciate our cultural resources.” Last year, their partner, the Desert Research Institute, gave a presentation at local schools, bringing in a drone to talk about current research and technologies, “which always sparks the interest of middle school and high school students especially,” Styles laughs.

Friends groups, grassroots organizations that form to protect places they love, are key to preservation efforts. Jim Stanger, president of the of Sloan Canyon National Conservation Area’s board, says the area counts 100-200 volunteers and three full-time rangers. Brenda Slocumb of Friends of Gold Butte National Monument, which contains hundreds of petroglyphs, estimates 25-40 volunteer site stewards and hike-leaders keep an eye on the monument and report damage to the BLM. Friends of Red Rock Canyon’s Terri Janison oversees 353 volunteers, who maintain 60 miles of trails and remove graffiti.

Expanding on the legacy of her father, Anderson is helping to ensure that the traditions of Paiute sign language and petroglyph interpretation do not disappear. In addition to working on a published edition of her father’s notebooks, she teaches three-day classes at a cultural camp for Southern Paiutes at Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument. Echoing Martineau, she says, “I can hopefully bring awareness to our own tribal people of who they are and what they were skilled at before it’s lost completely.” Φ